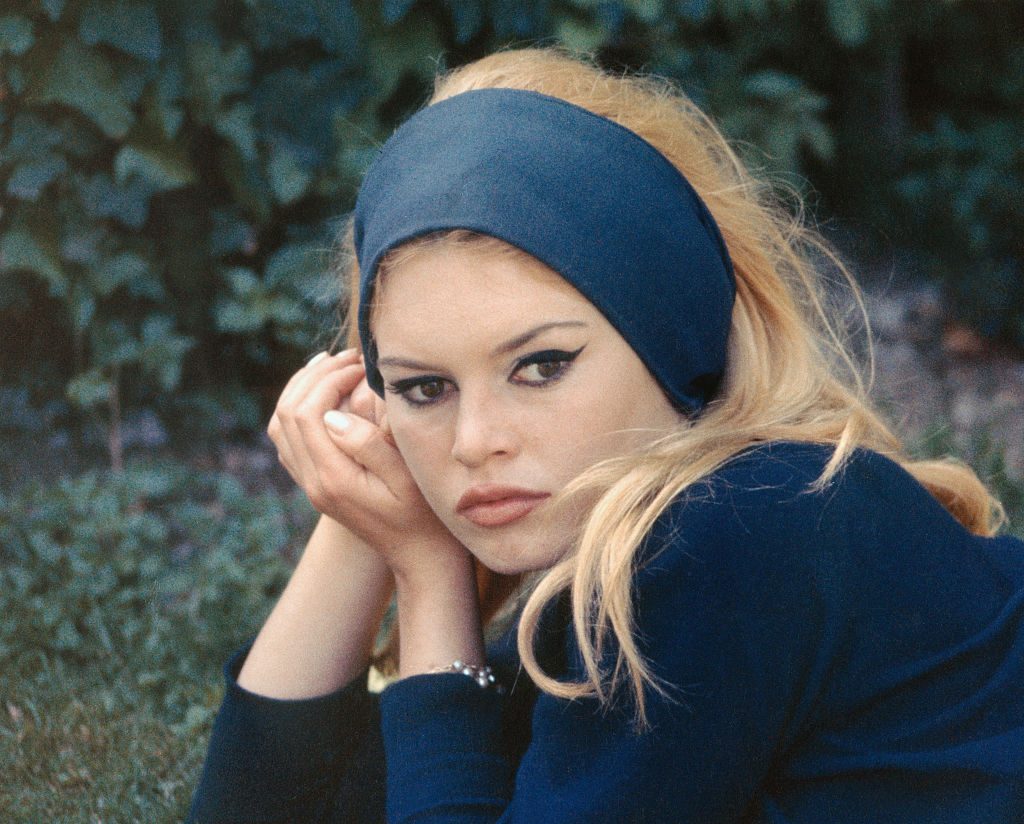

In 1968, shortly after her only meeting with Charles de Gaulle, then the President of France, at an Elysée dinner, Brigitte Bardot’s face was chosen to become the first modern representation of Marianne, the national emblem since the Revolution two centuries earlier. Even today, though newer versions were duly commissioned (depicting celebrities ranging from Catherine Deneuve to Inès de La Fressange), her upturned nose and pouting lips, from a cast by the sculptor Aslan, are still those most frequently found presiding over weddings and municipal ceremonies in the country’s 36,000 city halls.

“She is the best-known French actress on the planet, and she has earned more money for France last year than [carmaker] Renault,” then-Culture Minister André Malraux pleaded with Yvonne de Gaulle, who not only played hostess for the Elysée dinner but also set the dress code for the Palace. A strict Roman Catholic, le Général’s wife had balked at inviting the twice-divorced Bardot, then 33 years old and the embodiment of sexual liberation.

Bardot, told to wear a little black dress and a strict chignon, showed up wearing a lavishly frogged hussar jacket from a men’s tailor, and with her long blonde mane flowing on her shoulders. Most of the académiciens and intellectual guests were entranced by her star quality. Attendees recounted that when she showed up, France’s historic wartime chief quipped: “What a lovely soldier!”

The actress, who has died at the age of 91, was for many years the symbol of French modernity. That wide Bardot smile, never equaled in or outside of Hollywood, was an affirmation of strength. By the time she met de Gaulle, she had made over 30 films with celebrated directors including Jean-Luc Godard and Louis Malle — and Roger Vadim, whose And God Created Woman propelled her to stardom in 1956. Vadim married and divorced her, and went on to become, famously, Le Frog who kissed three princesses (his memoirs are modestly entitled Bardot, Deneuve, Fonda).

No one expected that in 1973 Bardot, the sex kitten that roared, would turn her back to movies forever in order to campaign for animal welfare. “I gave my youth and beauty to men. I will give my wisdom and experience to animals,’ she later confessed. Few believed at the time that she truly wanted out, that the gloriously raw sexuality which seemed to make addicts of the men in her life had not made her happy: that would have been an admission of guilt from us all.

Her first film for Malle, 1962’s A Very Private Affair, tells the story of a film star chased by fans and paparazzi, and exploited by directors and businessmen, until she throws herself from a rooftop. It may have felt prophetic to her. Five years later, Malle brilliantly cast her in Viva Maria, a revolutionary romp set in South America, as one of a duo of gun-toting traveling singers, placed on equal footing with the fiercely intellectual Jeanne Moreau. Revolution and sex: here was Bardot the feminist. “She was what I was not, and I was what she was not,” Bardot said after Moreau’s 2017 death. “We were not friends in the pretty sense of the word: we were accomplices, like two sisters can be. Rivals, sometimes, but in a good way.”

I interviewed her just once, on the telephone, four decades ago. It was a rainy winter evening for us both; she was in her St Tropez house while I was almost alone in a Paris newsroom, listening to the famous Bardot voice. She had not yet remarried — that would come in 1992; her last husband, Bernard d’Ormale, a former adviser to Jean-Marie Le Pen and by all accounts a kind man who reconciled her with her only son, survives her — and you could feel the weight of a chosen loneliness, full of the empathy no one had required from her when she was famous. You could also hear strength and willpower. Of course, she only wanted to talk about animal suffering. Tasked by the editor to suss out some gossip, I listened instead to the stories of the cats, dogs, donkeys and horses she’d saved.

As with Alain Delon, the only other French actor who could equal her in symbolic and very real international radiance — and like her a fierce Gaullist — animals were Bardot’s chosen partners, ones which remained impervious to the outside world. Delon died last year and lies buried next to his animals. Bardot leaves a respectable foundation dedicated to what she saw as her true life’s work. Perhaps we should listen to them.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe