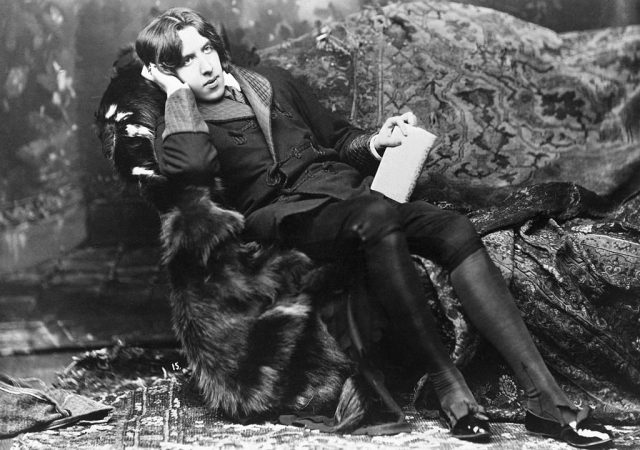

Wilde wished to convert sooner — but would have been disowned. Credit: Getty

To encounter a priest at an artist’s garden party in Brooklyn seemed like a very strange thing in the spring of 2022. The artist — the painter and writer Veronika Sheer, widow of the abstract expressionist painter Ron Gorchov — was a Jewish convert to Catholicism, drawn in years before by a sudden insight while contemplating a Giotto fresco. But her typical guest, balancing their wine and cheese on tippy little tables among the willow fronds and tulips, was young, eccentric, and non-religious: painters wildly pattern-matching their vintage clothes, genderqueer women in Carhartt work gear, or men with painted nails. The priest, Father Paul Anel, turned out to have a special mission to artists, which made it only slightly less strange. “Artists are seekers,” he told me, “and often they are troubled, and have experienced a lot of suffering; the Church should reach out to them.”

He was right about the general state of mind of the artist. I, a writer, could attest to that. But Roman Catholicism, the religion of scolds and prudes and patriarchal oppression, seemed unlikely to help anyone. Little did I know that a few weeks later, I would have my own mystical conversion experience and, in 2023, would become a member of Father Paul’s congregation.

Nor did I realize I would be part of a trend. Catholicism is hip once again, and writers, artists, and intellectuals are converting in droves. One church that draws such an audience, St. Joseph’s Church in Greenwich Village, has seen 10-fold growth in conversions in just a few years: more than 100 participants signed up for its catechetical program this year, up from 15 just three years ago. Eighty percent of the congregation’s members are in their 20s and 30s, according to Father Jonah Teller, a Dominican Friar who is a priest at St. Joseph’s. Numbers are similar at the Basilica of St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral, another Manhattan parish that is, for lack of a better word, cool.

A new book, Converts: From Oscar Wilde to Muriel Spark, Why So Many Became Catholic in the 20th Century, by UK-based Irish journalist Melanie McDonagh, addresses a wave of conversions among the artists and intellectuals of the previous century, and incidentally sheds some light on our own time.

More than half a million people in England and Wales converted to Roman Catholicism between 1910 and 1960, McDonagh reports, including an unusually high concentration of the era’s most influential artists and writers: Aubrey Beardsley, Graham Greene, and Elizabeth Anscombe were just a few of the bold-face names. They were going against their country — where the Church of England reigned, and Catholicism was viewed as the superstition of the underclass — and their era, in which religiosity overall was waning. The trend ended abruptly after Vatican II, which, ironically, was the Church’s attempt to modernize and make the religion more accessible and appealing.

McDonagh’s book is organized chronologically and by artist, starting in the 1890s with Oscar Wilde, who had a lifelong flirtation with Catholicism and converted in 1900 on his death bed. Wilde’s motivations, she says, were similar to those of many of the fin de siècle artists, in terms of being a mixture of mysticism and rebellion. His cohort may have been drawn to religion, but it was also reacting against Victorian elders, who’d embraced science, reason, and a deadening kind of materialism. If it wasn’t Catholicism, it was theosophy à la William Butler Yeats, or the occult.

Catholicism in the early 20th century was also a form of resistance against the dehumanizing aspects of industrialization, McDonagh argues. She quotes art historian John Rothenstein’s theory that since the Catholic Church’s primary concern is the salvation of the individual, and since the Church demands the individual take responsibility for his own salvation, Catholicism worked against the “standardizing tendencies inherent in modern society” and offered adherents a kind of autonomy otherwise lacking in their lives. A commune and back-to-the land movement ran alongside the conversion trend, even back then.

In many ways, Converts gets a slow start with Wilde and his peers. McDonagh is a workmanlike writer, presenting the biographical details without much peering into her subjects’ souls — the matter of greatest interest in a conversion story. We learn that people entered the Church because their friends did, or because they decided it was “the real thing,” or as a matter of reasoned theology. Many were influenced by Cardinal John Henry Newman (now a saint and Doctor of the Church), a former Anglican priest and theologian who first labored to transform the Church of England to be more like Rome, and then abandoned it, at great personal cost, for Rome itself. Newman died in 1890, but his writings led several of McDonagh’s subjects to conclude the truth of Rome’s claim to being the one true Church, the only one that had “continuity with the pre-Reformation Church,” as novelist and Catholic priest Robert Hugh Benson put it.

Converts renders this profound transformation somewhat bloodlessly — we understand that Newman was instrumental, but don’t quite catch the divine spark. Newman, more than anyone else in the modern era, made the case for a definitive and exclusionary Catholic truth; by rejecting the Church of England, he rejected the Reformation and all of Protestantism. His claim is historical — the Roman church is the only body that can trace an unbroken lineage to the apostles — and metaphysical: there is one truth, not many, and one institution to interpret it. Modern, liberal thinking often attempts to elide the radicalism here, imagining this as just one of many options that “all lead to the same place,” as the cliché goes. But that isn’t how the Catholics see it.

Even if McDonagh doesn’t quite bring Newman alive, themes emerge after he appears. The converts are looking for this kind of definitive truth. They leave the Church of England because of its Protestant waffling on dogma, or because they’re inspired by a longing for “spiritual order,” as convert and literary critic Maurice Baring said. To acknowledge “reality” was to become free, he wrote. Writer, convert, and Catholic apologist G. K. Chesterton explained it thus: “As for the fundamental reasons for a man joining the Catholic Church, there are only two that are really fundamental. One is that he believes it to be the solid, objective truth, which is true whether he likes it or not; and the other is that he seeks liberation from his sins.”

I joined the Church for neither reason — at least, not explicitly. I knew little of Catholic dogma. However, much of the joy and glory of the past few years has been in watching the world realign along this axis, as I conform my behavior to God’s truth, not my own. I’ve found answers hiding in plain sight to questions I’ve been asking for a lifetime, and it has been liberating.

Likewise, the stories in the second half of Converts seem to center on Catholicism’s fundamental claims and challenging structure — though, of course, ultimately they center on God. The religion made significant inroads among the English population during World War I. For Catholics, it matters if you have confessed your sins and received absolution before going into battle; the ritual is more than symbolic. Consequently, the Church sent its priests to the front lines to offer such sacramental ministry, while Church of England policy was for clergymen to avoid the fighting. McDonagh quotes Robert Graves’s observation that the enlisted men had “no respect” for stay-behind clerics, who seemed to have little more to offer than a final cigarette. Graves wrote admiringly of a Catholic priest, who “after all the officers had been killed, ‘stripped off his black badges’ and, taking command of the survivors, held the line.” Elsewhere, we read of priests crawling through the rubble during the blitz, to hear confessions and absolve trapped survivors.

Poet, painter, and engraver David Jones, whom McDonagh describes as “one of the most significant artists of the 20th century,” was first called to the faith during the war, when he had an epiphany after stumbling onto a Catholic mass in the “panorama of desolation” at the front. Jones discovered a reality to the service that he felt had always been missing during the Anglican office. Later, he wrote that artists had to be Catholic, and that “even if the Catholic religion weren’t true, you’d have to, [as an artist] become one … because the whole notion of art … is frightfully like the doctrine of transubstantiation.” A work of art, he believed, fundamentally was two things: an impression of a thing, and a thing itself. Just as the mass wasn’t a mere symbol or memorial of the sacrifice of Christ, but a portal renewing the real thing.

The acerbic novelist Evelyn Waugh believed the religion was equally essential for artists, but understood it differently. If an artist didn’t understand the relationship between God and man, the work would be a failure, Waugh thought. In his view, Henry James was the last of the great writers. And modern, secular novelists, he wrote, “try to represent the whole human mind and soul and yet omit its determining character — that of being God’s creatures with a defined purpose.” If the artist didn’t understand the true grounds of man’s existence, Waugh believed the characters could only be “pure abstractions,” a stakeless and boring task for literature.

It’s not a bad theory of what’s happened to books in our increasingly secular age, though a great Catholic novel revival has yet to accompany the 2020s wave of conversions. To understand the trend today, many of the ideas in McDonagh’s book are useful. As at the fin de siècle, we live in a science-ruled, rational, materialist time, one which often seems to have little to offer the deeper human longings. Techno-feudalism is even more oppressive to our individuality than industrialization was. And of course, in a time of ultimate permissiveness, a devout and restrictive religion is a tiny bit contrarian and rebellious.

Father Teller floated other reasons for the conversion trend to be happening now. “Gen Z is lonely,” he said, noting that the cohort came of age during the pandemic. “And they’re looking to be told who they are, and who cares for them.” He speaks frequently to young artists, musicians, and intellectuals seeking to convert, though they’re not the majority of his flock. Another reason for the appeal, he adds, is that “all the institutions are breaking apart, but the institution of institutions, the Church, remains.”

A newly traditionalist bent in some parishes (and notably, the popular ones) — less Vatican II, more Latin and “bells and smells” — may also be playing a role. The final chapter of Converts is a sad one, as McDonagh details what the changes of the 1960s wrought upon many of her subjects. She’s careful to disclaim that many people may have liked the new mass and the more accessible format, but those drawn to the Church by authority and tradition did not. The collapse in conversion numbers is not conclusively because of Vatican II, but after it, collapse they did: to 6,046 new adult converts in England and Wales in 1970, down from more than 15,000 a decade earlier In both 2021 and 2022, the number was under 2,000. Still, McDonagh writes, there has been a modest increase lately, and “the story continues.” More artists and communicators should only amplify the trend.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe