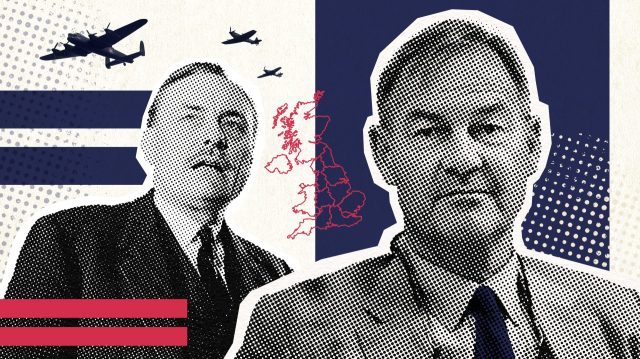

Powell, left, remains a radioactive presence in British immigration discourse. (Credit: Getty)

Rupert Lowe deals in the politics of return: illegal immigrants are going back, and so is Britain. The Great Yarmouth MP, formerly of Reform UK, has now launched Restore Britain as a new political party, and on Wednesday evening claimed that it had passed 70,000 members. The launch announcement was marked with a stirring video of Lowe in his farmer’s get-up, as well as a series of semi-ironic nationalist compilations presumably made by Restore’s Zoomer footsoldiers. In one of these, among nostalgic nods to Geoff Hurst and Zulu, 1997 is invoked as the year when everything started to go wrong. Speaking over grainy images of a lost Britain, Lowe sums up his political outlook: “I think the state is bad, and I think the individual is good.”

One area where the state has undoubtedly failed, in Lowe’s eyes, is on the matter of immigration. While Reform has pledged to deport all illegal immigrants, Restore wants to go further. Lowe has promised to scrap the asylum system entirely, also stating last week that “legal immigration will almost come to a complete halt.” The goal is not just to halt migrant influxes but to reverse them. “Net zero immigration is weak, weak, weak. It is insufficient and it is too late,” he said in the speech with which he launched the party. “The barbarians are already in the gates.”

The remedy, Lowe warns, will be “incredibly painful”: a characteristically abrasive verdict. It is one thing to criticize quangos, and quite another to say that “we must crush parasitic Britain.” And as for the dissonance between government and individual? “The state has definitively become the enemy of the people.”

In his doom-laden pronouncements, Lowe resembles no British political figure so closely as Enoch Powell, whose 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech has led a radioactive afterlife in the national consciousness. For Powell, Britain’s willingness to take in tens of thousands of immigrants rendered it “a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre”. And compare Lowe’s talk of necessary pain to that 1968 call for an “extreme urgency of action now, of just that kind of action which is hardest for politicians to take”. For better or worse, Powell presaged contemporary debates over migration and nationhood. The challenge, as Keir Starmer found out with his more milquetoast “island of strangers” line, is to acknowledge voters’ frustrations without sounding like him.

Powell has been a political lodestar of sorts for Nigel Farage, Lowe’s bête noire and former boss who suspended him last year over dubious accusations of bullying. The Reform leader recalled being “dazzled”, as a schoolboy in the Eighties, listening to the former Tory MP speak. Last year, he insisted that Powell was fundamentally right about the scale of “community change” in the country.

Yet, in his beliefs as well as his rhetoric, Lowe is a more obviously Powellite figure than Farage. He’s more interested in reducing the size of the state, is resistant to Reform’s nationalizing impulses, and is less vulnerable than his rival to charges of “socialism”. In many ways, Restore is the more conservative project, given that its central mission is to return Britain — in more explicit terms than Farage has dared — to a glorious past from its Blairite present. When it comes to presentation, Farage and Lowe — tweed-clad former public schoolboys with past lives in the City — are far closer to one another than they are to the intense, prodigiously academic Powell. Former Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan found him unsettlingly zealous, complaining: “Powell looks at me in Cabinet like Savonarola eyeing one of the more disreputable popes.”

Where Lowe differs from Farage, though, is that he has done less to distance himself from figures and ideas which might be classed as far-Right. While the Reform leader has condemned Tommy Robinson for “stir[ring] up hatred” and stated that the activist has no place in his party, Lowe has praised Robinson’s campaigning against grooming gangs cover-ups. In 1974, Powell rejected the chance to stand as a candidate for the far-Right National Front, having left the Tories because of their stance on the European Economic Community.

Lowe would be wise to take such an approach with some of the groups and activists now attempting to tie themselves to Restore. Paul Golding, the leader of the far-Right Britain First, has said he won’t stand candidates against Lowe’s party at local or national elections. Steve Laws, a prominent ethnonationalist who advocates for the expulsion of everyone who is not ethnically British, has committed his vote to Restore Britain and called Farage a “traitor”. On Monday, he posted to his 140,000 X followers: “I fully endorse Rupert Lowe to be PM. He will implement the majority of what I want to achieve in terms of remigration over the next 6-7 years.”

These activists are unlikely to appeal to swing voters. Lowe, if he follows conventional electoral logic, is therefore presented with a dilemma: how to attract smart collaborators committed to immigration restrictionism, without also drawing in the cranks? The problem is that a cruder vision of nationalism pervades even the upper echelons of his party. Harrison Pitt, a writer who has been a key figure in devising policy for Restore Britain, has previously referred to mass immigration as the “ethnic cleansing” of white Britons, as well as highlighting the “erasure of [Britain’s] host population”. Additionally, he has appeared to suggest that Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood, whose parents were born in Pakistan, should return to her “homeland”, and vowed in December to make 2026 “the year of mass denaturalizations” for those who presently hold British citizenship.

In an interview in December 2024, Lowe said that “I don’t care about people’s religion or their color,” but Restore has taken a far more robust approach to Islam than Reform has. Lowe is set on “resisting the relentless creep of radical Islam”, and his new party’s platform includes policies on outlawing the burqa, sharia courts and halal slaughter. Some of its senior figures also champion a notably muscular Christianity. For instance, Lowe’s campaigns director Charlie Downes, a Catholic convert, declared this week: “Restore Britain believe that Britain is a people defined by indigenous British ancestry and Christian faith.”

Both Downes and Pitt are still in their twenties, and Lowe has a notable following among a particular group of politically engaged, digitally-savvy young men. There’s even a collective term which can be used either pejoratively or affectionately: Lowemosexuals. The online sphere has become a battlefield between the Restore leader and Farage, who boasts more TikTok followers than the other 649 UK MPs combined. Lowe last year labeled the Reform boss’s leadership style “messianic”, yet his own role in Restore follows similar contours, the party’s profile relying largely on his social media reach.

Capturing wider support, of course, is a different proposition. According to polling from this week, 92% of Britons are unable to name Lowe when shown a picture of him. He is popular among his constituents, viewed as a committed and unpretentious champion for Great Yarmouth, but he has a majority of less than 1,500. He is expected to stand at the next election under the banner of Great Yarmouth First, which he established as a political party in December, yet his personal appeal may count for less when divorced from a Reform UK platform.

So the question remains: is Restore a credible Right-wing movement — able to distinguish itself both from Reform and from the crowded field of nationalist groups on the more radical fringes — or just Lowe’s revenge project? County councillors are already moving over from Reform, providing some local infrastructure. Even if Restore doesn’t win seats at the next election, it will surely still prove a spoiler for further Farage gains.

Here, Lowe could receive extra ammunition from an alliance with another of Farage’s jilted exes: Ben Habib. Having served as co-deputy leader for Reform, Habib was demoted in favor of Richard Tice, and quit the party in November 2024. The following spring he referred to Lowe’s treatment by Farage as an “injustice”, subsequently setting up a new party of his own, Advance UK, in June.

On Saturday, Habib extended an open offer to Lowe to merge their two parties. Lowe politely demurred by suggesting that Habib join Restore, which “would be stronger with you in it”. But Habib, who was born in Pakistan and moved to the UK as a teenager, is not widely popular among the hardcore Lowemosexuals. David Kurten — who leads the Heritage Party, another bit-part player in Britain’s hard-Right scene — summarized the dynamic thus: “Ben loves Rupert. Rupert’s fans would deport Ben.” Richard Inman, a prominent Advance UK member and organizer for Tommy Robinson, has accused Lowe of being “driven not by love of country, but by a massive ego”, adding that many of Restore’s supporters are “ethno-nats”.

Advance has built up a respectable profile: it now has more than 40,000 members, nine councilors through defections from Reform, and outsized publicity thanks to endorsements from Tommy Robinson and Elon Musk. But the Tesla mogul, as well as boosting Habib’s party, has in recent days cheered on the progress of Restore Britain. On Wednesday afternoon, he went so far as to accuse Reform of being “Nazis” because “THEY are the ones who want race extinction.” As the world’s richest man, armed with 234 million pliant X followers, Musk’s overseas influence is considerable; his amplification of posts about the grooming gangs helped push the Government into ordering a national inquiry.

Musk is widely reviled among British voters, but his support — both X-based and financial — could boost Restore’s international profile and increase the chance of collaboration with like-minded parties such as Alternative for Germany and Spain’s Vox. Farage endorsed the AfD in 2017 but has, in recent years, kept a deliberate distance. There is a gap here for Lowe to exploit as anti-immigration groups build ties around Europe: these are parties which are gaining influence but which are still considered too dangerous by Reform and the Tories.

While Farage might think he flies in the face of such squeamishness, and that he is dismantling the “uniparty” consensus, Restore supporters believe he instead represents little more than a continuation of the New Labour-inflected order which has governed Britain for the past three decades. According to Downes, Reform’s senior figures “basically agree that the vision Blair had for Britain was admirable and desirable”. In his view, “it will come to pass that Farage is the Regime’s lifeline, not its nemesis.”

Lowe’s calculation may well be that he doesn’t need to expunge the less savory elements from his party’s message, and that the electorate will instead move closer to him. The UK’s Overton window has undeniably shifted on immigration; Labour’s Home Secretary, Shabana Mahmood, is taking a harder line than her Tory predecessors, even as the polls are led by a party with a plan for mass deportations. Almost half of Britons say they would support an agenda in which no new immigrants are admitted to the country and large numbers of recent arrivals are required to leave. British voters’ conception of national belonging remains chiefly civic, but some of Lowe’s most influential cheerleaders believe there is further room for that ideological window to move.

Either way, the Restore leader is not one for apologies. On Wednesday, he wrote that he is “entirely uninterested” in “being called unpleasant names”. He has repeatedly made clear that being labeled racist is no deterrent for him. Pushed to recant a suggestion that illegal immigrants should be sent to remote Scottish islands for the “midges to do their work”, he doubled down. Lowe, evidently, has a thick skin. In his previous life as chairman of Southampton Football Club, disgruntled fans used to sing about hanging him from the Itchen Bridge.

It’s easy to forget that, even after “Rivers of Blood”, Powell was immensely popular. Polls carried out shortly after the speech demonstrated that a majority of the British public agreed with his assessment of race relations. In 2002 he was voted one of the 100 greatest Britons ever. On his death, the Telegraph wrote that he “would survive more surely than any other British politician of the 20th century except Winston Churchill”. Just as Powell’s fears around integration proved prophetic, Lowe may now find himself a 21st-century equivalent — an emissary from a future Britain whose decline has been contingent on its tolerance.

Ferdinand Mount, who headed the No. 10 Policy Unit under Margaret Thatcher, wrote of Powell that “always, he is restlessly pursuing the ultimate safe haven: the nation.” Nationalism’s great strength, for Mount, is its “iron framework” — the “insistence that the nation is the supreme political fact”. The very act of restoration inherent to Lowe’s project is its own safe haven, as inarguable in its logic as “Make America Great Again”. He, like Powell before him, has recognized the British state as the sclerotic, rulebound husk it is. And now, as Powell was, he is filled with foreboding.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe