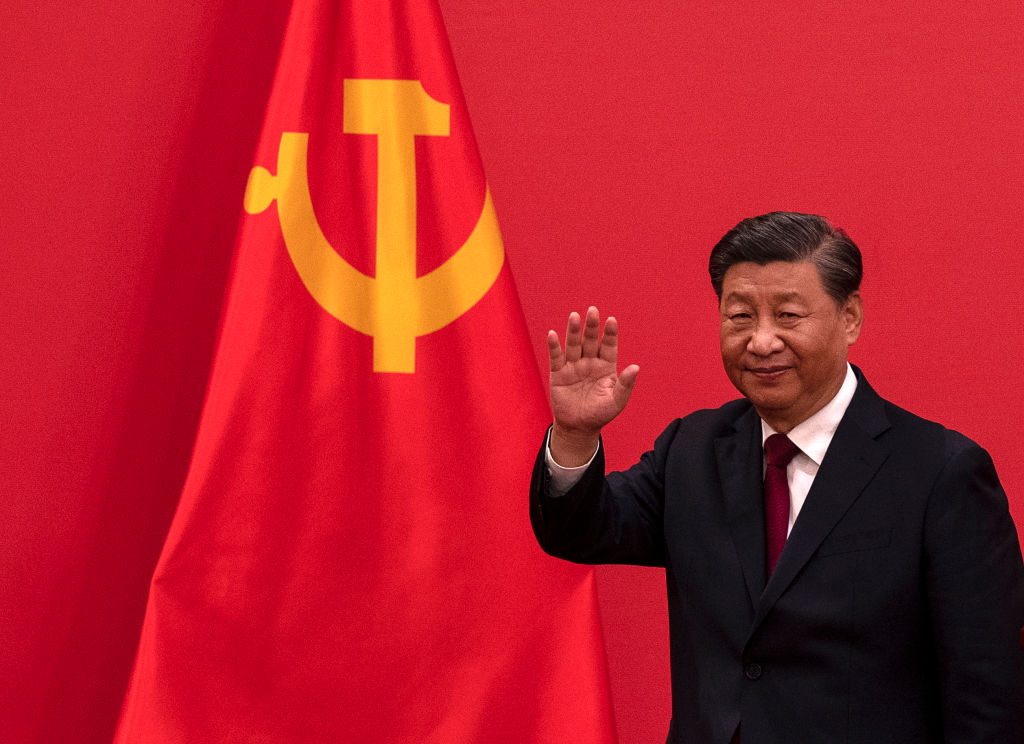

Chinese President Xi Jinping has confirmed what many may have thought for a while: that he wants to make the renminbi capable of rivaling the dollar as the global reserve currency. His remarks represent China’s boldest statement yet about its ambitions to become a global financial power. They aim to seize the moment, exploiting unease over Donald Trump’s readiness to reshape the world through US financial hegemony. But it begs the question: can China offer a salient, stable alternative?

As of 2025, the US dollar still accounts for roughly 57% of allocated global reserves, down from 71% in 2000, but remains dominant. The renminbi, however, ranks sixth, at around 1.93%, behind the euro (20%) and even the Japanese yen (5.82%). For countries like Russia or Iran, pushed out of dollar-dominated financial channels, settling trade in China’s currency would seem as though it’s a solution. But for the rest of the world, it’s hard to see the renminbi as a credible long-term store of value.

This is because reserve currencies aren’t chosen based on whether or not world leaders support them. They’re chosen because global investors and central banks trust the systems behind them. Dollar dominance was forged through deep, liquid capital markets, strong property rights, and judicial independence, then cemented by military credibility demonstrated in two world wars.

China doesn’t offer that. It offers capital controls, opaque policymaking, state discretion over markets, and limited legal protections for foreign (and domestic) investors. That’s hardly inspiring for the confidence that a reserve currency demands.

Nevertheless, the main source of skepticism about the renminbi is political, not technical. If the aim of moving beyond US hegemony is greater multipolarity and financial autonomy, then simply replacing Washington with another dominant power is self-defeating. A system centered on a country that controls vast global supply chains risks becoming even more constrained.

Giving Beijing comparable monetary centrality would unite industrial and financial power in a single state. The United States became the dominant reserve-currency issuer after the Second World War while holding an enormous share of global manufacturing, but supply chains were still largely national. China today sits at the center of far denser and more inescapable global production networks.

Beijing’s position is structurally different. With a $1 trillion trade surplus, China sits at the center of modern global manufacturing in a way that is deeply integrated with the rest of the world’s economies. Even countries that resent American overreach should hesitate before endorsing a system that could make a single state both the factory and the banker of the world.

In the multipolar era, what countries should be aiming for is to move towards diversification of reserve currency, rather than trying to find a singular alternative to US dominance. We may see more local currency settlement in trade corridors, bilateral swap lines, redundancy in payment systems, and stores of value that aren’t instruments of another state’s foreign policy, like gold or crypto.

None of this means the dollar is untouchable, but even in a context of diversification, the American currency is likely to remain dominant. The reason is not that the world loves Washington, but rather that it remains the best-proven option among the alternatives. The renminbi may improve its standing, but concentrating monetary power in a nation that already dominates manufacturing would be a strange solution to the US dollar hegemony.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe