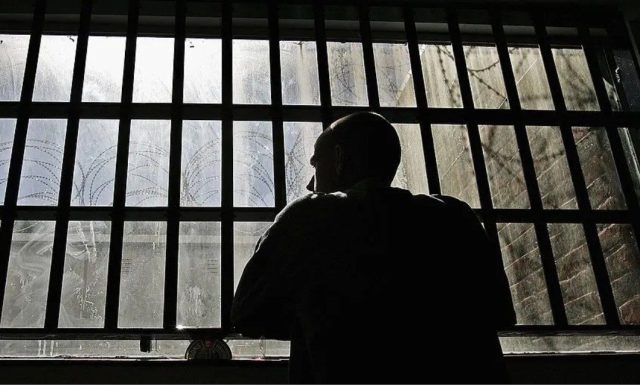

'This is not about romance or scandal. It is about safety.' (Peter Macdiarmid/Getty)

The wing is sealed for lockdown at HMP Gartree, a Category B lifer jail. The corridor is so quiet that even the light footsteps of an officer can be heard shuffling along. A knuckle taps the hatch; a whisper follows. Two voices lean into a thrill they know they shouldn’t indulge. Lingering too long. Returning too often. Small signs, but unmistakable to those of us locked behind our cell doors. Scenes like this were common in a closed world where boundaries matter, because they are the first line of defense between order and opportunism.

Despite today’s headlines about officers being sacked or jailed for illicit relationships with prisoners, none of the underlying dynamics are new. Across the 16 years I spent in custody, I saw it all first-hand, from furtive tenderness to outright corruption. But if base human impulse will endure until our jails turn to dust, the prison environment has changed. With austerity undermining the workplace structures that once controlled interactions between inmate and guard, hormones — and self-interested cynicism — are now far harder to constrain.

A recent surge in misconduct cases has dragged prison romance into public view. The media focus has fixed largely on women, partly because several cases have been unusually sensational, from the explicit footage to relationships that fused emotional dependency with criminal compromise. The HMP Wandsworth case, where an officer was jailed after being filmed having sex with a prisoner, illustrated how quickly fantasy, contraband and security failure can collapse into public scandal.

The figures reflect this trend. In the year to June 2024, a record 165 prison staff in England and Wales were dismissed for misconduct, a 34% rise on the previous year. The offenses ranged from inappropriate relationships to smuggling phones and drugs. Across the wider Ministry of Justice and its agencies, dismissals for misconduct have more than doubled since 2022. Increased detection doubtless plays a role here, but so do the cumulative effects of structural degradation. Ironically, the very contraband used to sustain secrecy — mobile phones — has helped expose wrongdoing so publicly that the state has been forced to respond.

In truth, though, this is about far more than a smuggled iPhone. There was a time, after all, when such relationships were contained by experience. Older officers understood prisoner behavior instinctively. They spotted manipulation early. They knew when a conversation lingered too long, when grooming had begun, when a colleague needed to be rotated off a wing. Their presence acted as the prison service’s immune system. I remember one senior officer who ran the wing I lived on. He was firm, sometimes abrasive, but effective. “It’s his train set,” a fellow prisoner once joked, and in a sense it was. He understood the environment and how to keep it stable.

That authority wasn’t abstract. One officer I knew, who become involved in an intimate relationship with a prisoner, was working under exactly this kind of robust leadership. Once the early signs were identified, there was no slow drift, no tolerated ambiguity. She was removed from the wing and marched off-site within hours. As it was relayed to us later, a superior told her simply: “This job is not for you.”

These protections were stripped away after 2012, when ministers replaced a planned privatization drive with “public sector benchmarking”: doing more work with fewer staff. From 2011 to 2017, frontline officer numbers fell by roughly 30%, and the service has never recovered.

When that senior officer I knew took redundancy, some were glad. Within a year, though, the cost was obvious. The atmosphere loosened. Boundaries blurred, and with them the everyday authority that had kept the wings stable. What followed was a power vacuum, one swiftly filled by violent criminals, organized gangs and Islamists. Authority, in other words, isn’t withdrawn from the landings, nor does it disappear. Rather, it’s ceded: to those most willing to impose it, arbitrarily and often violently.

And for every experienced prison guard who retires, their replacement is almost invariably worse. I saw this first hand, as landings were filled with inexperienced recruits, some barely out of college, and all with minimal training and weak supervision. A vicious circle soon followed, as staff with little life experience were dumped into some of the most brutal environments in the country. I witnessed this shift personally, when a new female recruit arrived on my wing. She was keen and professional, but inexperienced in reading her surroundings. That is not a criticism of her; it’s an obvious risk when 22 year olds are stationed on wings holding around 100 men, and where they’re routinely left to patrol landings alone. High on the third floor, the guard was dragged into a cell by a prisoner serving a life sentence for murder, with no colleagues to assist her. Intervention came only after other prisoners heard her screams.

By late 2023, the scale of this collective inexperience was stark. 41% of prison officers had fewer than three years on the job, compared to just 2% a decade earlier. Meanwhile, the proportion with over 10 years’ experience had fallen from two thirds to less than a quarter. Knowledge that once passed informally between generations of staff — how to read a wing, how to set boundaries — had largely disappeared.

As my memories from HMP Gartree imply, secret relationships between inmates and guards have always existed. Falling in love is human nature, more so in the cramped psychological conditions of prison. Jail distorts ordinary emotional patterns. It compresses isolation and allows human instincts to slip their usual restraints. All this is doubly true for prisoners, starved of intimacy and connection, with deprivation turning small acts of kindness into oxygen.

Yet seasoned criminals hardly forget their methods at the prison gate. They cultivate familiarity, test boundaries — and wait. Once a line is crossed, leverage follows. A favor today becomes expectation tomorrow. Then exception becomes routine, and emotional access hardens into material extraction: contraband, prohibited communications, the “one-off” that last for years.

For officers, particularly young women placed on volatile landings with predatory men, environment and emotional reflex combine with dangerous force. There is the urge to nurture, easily triggered by displays of distress or vulnerability. There is the pull of charismatic alpha males who command status among dangerous peers. And there is flattery, the illusion of being uniquely trusted, understood or “liked”. Some slip into the role without quite knowing when the ground gave way. Others exploit it knowingly, sometimes for financial gain.

Whatever the reason, falling into crime, especially when your duty is to maintain professional boundaries and protect the public, is a choice. Yet when these forces collide with inadequate supervision, thin staffing and relentless exposure, they harden into risk — and the consequences can be severe. Intelligence leaks. Contraband circulates more freely. Debt and violence intensify. Informal power shifts. I have known officers disclose offenses, identify informants or pass on sensitive information, sometimes to ingratiate themselves, sometimes out of hatred for a particular crime. The consequences were predictable: prisoners attacked; debts enforced through beatings; men removed from rehabilitative pathways because trust, once broken, could not be restored.

Of course, not every case crosses the threshold into criminality. Some drift into genuine emotional partnerships. A small number of staff resign to continue relationships openly once prisoners are transferred. In lower-category prisons, this drift has sometimes been rationalized rather than challenged. At HMP Warren Hill, where I was held for over two years, one such relationship involving a charity worker was tolerated on the basis that it acted as a “protective factor” ahead of release, provided it remained “non-intimate”.

Still, just like in the real world, many of these staff-inmate relationships founder, and when they do, officers tend to suffer more. If the breach involves improper contact but no contraband, the (often female) officer is removed, barred and sometimes shamed in the press. The prisoner, however, may face little consequence beyond a file note. When criminality is involved, the imbalance widens further. Messages, footage, and entry logs usually sit with the officer. When it collapses, it does so brutally: prosecution, reputational ruin, shattered families and the realization that the promise of love was often as empty as the cell she now occupies. He, practiced in the art of concealment, may simply continue serving his sentence, his network and status enhanced.

His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service has acknowledged part of this reality, expanding its Counter Corruption Unit from 2019 to detect and disrupt wrongdoing. The rise in dismissals reflects that effort. But enforcement alone cannot repair a degraded system. This, too, reflects a wider failure across Britain’s criminal justice system: risk is managed procedurally rather than structurally. Scandals are treated as isolated lapses rather than symptoms of institutional weakening. Responsibility is pushed downwards onto individuals, while the conditions that made failure predictable remain largely untouched.

Honest reform would begin by honestly diagnosing the problem. This is not just a morality tale about individual weakness, but the predictable result of stripped-out experience, supervision and authority. From there, the authorities must re-professionalize the job. That means restoring experienced staff on wings, and ensuring training addresses the ethical and psychological hazards of prison work, all while rotating staff off high-risk landings. The watchword here should be prevention — not punishment.

Aligning incentives with reality is crucial here. Stabilizing violent, drug-saturated prisons is skilled, risky work. Until pay and progression reflect that, the service will continue recruiting for numbers and losing experience. And finally, the Ministry of Justice should improve design and culture, not just detection. Better sightlines and smarter CCTV both matter here, as do schedules that discourage isolation.

Ultimately, this is not about romance or scandal. It is about safety. Yet until prisons are rebuilt as safety-critical institutions — properly staffed and properly supervised — the same quiet patterns will persist: the light footsteps on the landing, the whispers at the door, the lines crossed just out of sight. And the consequences will not remain inside.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe