Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

The air inside the Harrisburg, PA kickoff for Robert F. Kennedy Jr’s “Eat Real Food” tour was thick with a chaotic kind of American energy. Looking around the State Capitol rotunda, nearly every part of the political compass was represented. There were young MAGA diehards in awkwardly fitting three-piece suits and broccoli-head haircuts, and older rural Republicans who were likely at the Pennsylvania Farm Show held there last week.

Then, at one point, I was approached by a thirty-something woman in a forest-green MAHA hat which partly concealed what the internet snarkily calls white girl dreads — possibly representing the “crunchy mom” demographic. She was signing up people for early ballots. Likewise, an elderly hippie type who could have been working at a health food co-op in Vermont was hawking colloidal silver supplements, telling potential customers: “I’m expanding my business because I’m not afraid of the FDA coming after us.” In any other year, the camo-and-denim versus yoga pants and dreamcatchers crowd may have been shouting at each other across a barricade. But in 2026, they were nodding in unison as Secretary Kennedy spoke about the new red-meat-friendly food pyramid.

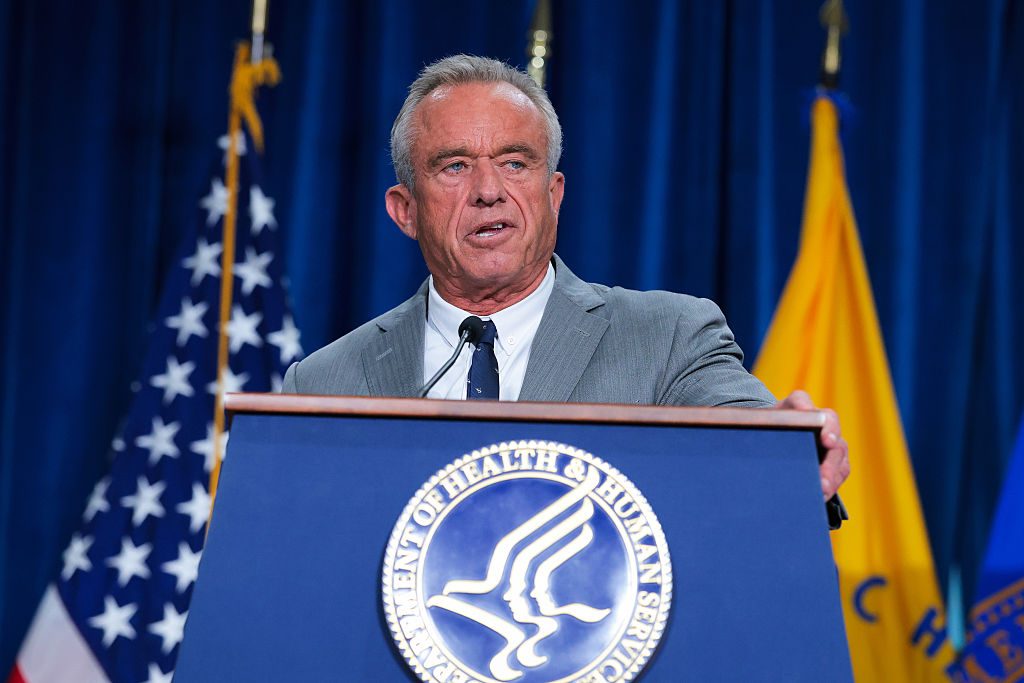

This is the paradox of the Make America Healthy Again movement. It’s a big-tent political project which represents an uneasy, even volatile, fit for both major parties in a time of hyper-partisanship. That was clear from watching the rally’s opening acts. Local statehouse officials took the stage first, delivering robust rhetoric that the GOP base has come to expect: their version of MAHA involved broadsides against Medicaid fraud, warnings about the expense of beta blockers and healthcare for trans people, and the standard bureaucratic grievances of the Right. But when Kennedy took to the podium, the channel changed instantly. He didn’t mention trans athletes or “welfare queens”. Instead, he spoke about the dangers of ultra-processed food and misplaced nutritional guidelines. It was as if two different planets temporarily aligned over a shared love of whole milk and hatred of Red Dye No. 40.

It underscores that MAHA isn’t a clean ideological project, instead existing in the gaps between Left and Right. The overlap stems from a deep-seated distrust of institutions, anxiety about societal decline, and a yearning for something less artificial in a deeply mediated age. Sometimes, it feels like a coalition of overlapping anxieties rather than a shared worldview. For some, health is about personal responsibility and discipline. For others, it’s about environmental degradation and corporate malfeasance or reclaiming bodily autonomy from institutions they no longer trust. That makes it confusing, uncomfortable, and easy to caricature, yet also one of the few political currents which doesn’t feel entirely pre-scripted.

Kennedy’s critique of monopolies and corporate power, his insistence on trusting the science (though perhaps not the science that Democrats subscribe to), and his skepticism of deregulation don’t fit neatly with a Republican Party still reflexively hostile to anything that smells like environmentalism or public-health intervention. The GOP has spent 40 years branding itself as the party of big business deregulation, yet here is its Health Secretary proposing what is essentially a massive, state-led intervention into the private sector’s right to sell Froot Loops with whatever ingredients they see fit.

MAGA diehards accept it because they trust the messenger, particularly since the GOP is starting to become the party of physical fitness. But the ideological fit is awkward. In some sense, they are cheering for Michelle Obama’s anti-obesity campaign in 2008 and the “nanny state” as long as the nanny is wearing a camo hat and questioning the FDA.

Conversely, the Democratic platform should find common ground here. For decades, the Left owned the “organic” brand. They were the ones worried about Big Ag and Big Pharma. Yet many Democrats and the liberal media seem incapable of engaging with the MAHA agenda beyond a singular, obsessive focus on vaccines. By reducing the movement to “anti-vax kookery”, they miss the broader, more potent appeal: a genuine, cross-partisan anxiety about the fact that America is getting sicker, fatter, and more medicated.

Whether the existing MAHA alliance can survive and succeed over the next three years is another question. Kennedy acts as a bridge between the hippie-ish “wellness” world and the “don’t tread on me” Right, but as MAHA moves from rallies to policy, the contradictions will become harder to ignore. For now, most people can agree on slightly shifting America’s grocery list.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe