Wikipedia has become the invisible editor-in-chief of the digital age. Its millions of entries sit at the top of Google search results, supply answers to Siri and Alexa, and help train leading artificial-intelligence models. For most people, it’s become the default reference library of modern life.

What most users of these “downstream” platforms don’t see is that Wikipedia has a distinct worldview — one that often stands in quiet opposition to the convictions of billions of religious believers.

This shows up in what the platform calls “Wikivoice”, the site’s institutional voice reserved for asserting uncontroversial facts. Take the article on “Yahweh”, the God of Israel. It opens by characterizing Yahweh as an “ancient Semitic weather and war deity”, recasting the central figure of Jewish and Christian monotheism as a local storm god and reducing core religious concepts to anthropological curiosities.

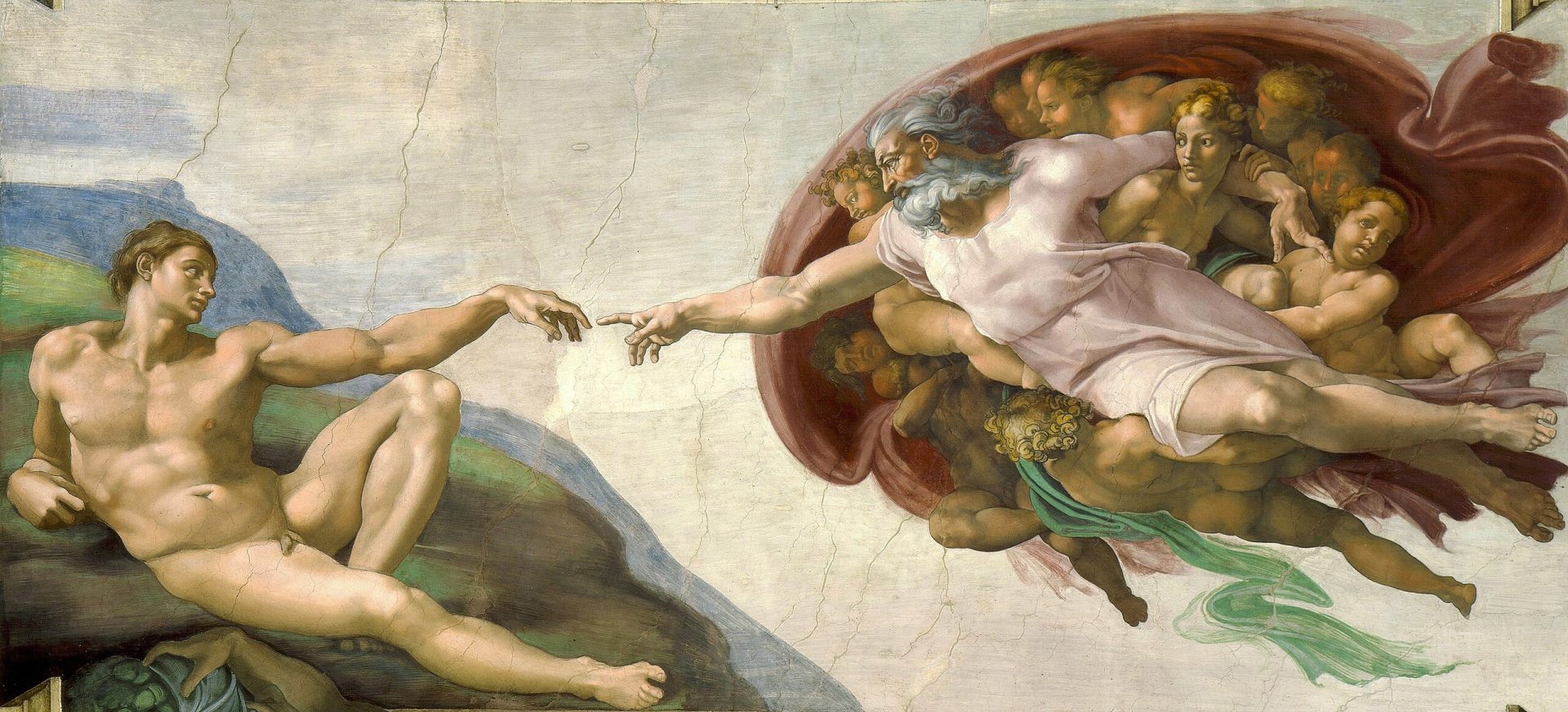

Or look at the entry on the Judeo-Christian account of creation, “Genesis creation narrative”. It describes the first lines of the Bible as a “creation myth”, which Wikipedia defines as “a symbolic narrative of how the world began and how people first came to inhabit it”. For billions of monotheists, Genesis isn’t a metaphorical tale in a comparative-mythology anthology: it is the authoritative account of the world’s origins. To see it presented as “myth” is fundamentally at odds with how believers understand their own faith.

There is nothing wrong with presenting skeptical or secular views of religious texts. That kind of analysis has a long and serious intellectual pedigree. The problem is that in relativizing religious accounts as one “myth” among many, Wikipedia treats a particular kind of secular scholarship as if it were simply factual description. What emerges isn’t neutrality, but a specific theology — a secular academic one.

The pattern is visible in other key articles. Consider the entry on the Septuagint, the ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. In the crucial lead section, Wikipedia cites “Biblical scholars” who “agree” that the text was translated by Jews living in the Ptolemaic kingdom. The traditional Jewish account— that 72 translators, six from each of the 12 tribes, produced the work — is moved to a section labeled “Jewish legend”. One view is presented as sober history, the other as folklore.

The intellectual engine behind this approach is “Biblical criticism”. Wikipedia defines it as the use of “critical analysis to understand and explain the Bible without appealing to the supernatural”, based on the belief that reconstructing the historical events behind the text, and the development of the text itself, will lead to “a correct understanding of the Bible”.

In practice, this method treats religious texts almost exclusively as products of human cultures and institutions. In its emphasis on the “instability of meaning, rejection of universal truths, and critique of grand narratives” (as Wikipedia describes postmodernism), this scholarship was a conceptual precursor to today’s postmodern frameworks. Wikipedia co-founder Larry Sanger has given this overall orientation a name: the GASP worldview — Global, Academic, Secular, Progressive.

The question isn’t whether scholars should be allowed to hold or publish such views. It’s whether a GASP perspective should be written into the operating system of the world’s default encyclopedia and then piped, unseen, into every search engine, smartphone and AI system that relies on it.

To see how GASP gets translated into editorial reality, look at how much power a small number of editors wield. According to Wikipedia’s own edit histories, large portions of major religion-related articles have effectively been captured by one or two highly active contributors. In the case of “Biblical criticism”, nearly all of the current article was written by a single editor, who explains on their user page that “‘mainstream’ scholarship is defined by critical method and what is verifiable historically. It is not a point-of-view or a philosophy, it is not found in the presence or absence of religious belief.”

One way to address this issue is through transparency. Wikipedia could disclose when a single editor has written most of a major article, especially in sensitive areas such as religion. It could label certain sections explicitly as representing academic-critical interpretations, rather than allowing them to speak in the site’s all-seeing “Wikivoice”. And downstream platforms — from search engines to AI systems — could stop treating Wikipedia as if it is the last word.

The problem isn’t that a secular academic theology exists. The problem is that it has quietly become the house theology of the internet. When a handful of unseen editors are effectively appointed as high priests of “neutrality”, we aren’t looking at an open-source encyclopedia. We’re looking at a new kind of magisterium — one that owes us far more honesty about what it believes.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe