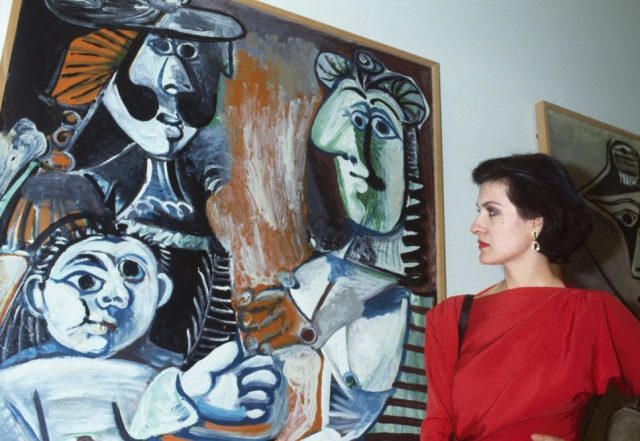

'By the end of its first quarter, the 20th century had already seen what many now consider its most groundbreaking artworks'. (Pierre Vauthey/Sygma/Getty)

Interwar Paris was a world-historic cultural incubator, one of the most fertile periods in the history of art, like 11th-century Baghdad or late 15th-century Florence. In his autobiographical Self Portrait, the modernist photographer and painter Man Ray provided an unparalleled picture of the explosion of radical art in the first decades of the 20th century. He described meeting many of the most influential creatives of the modern era: architects, film directors, composers, painters, sculptors, novelists, poets, playwrights, fashion designers, journalists. He claimed to have photographed every one of them. The archives suggest he actually did.

Yet what’s most fascinating about that world was how fragmentary, improvisational, and messy it appeared to the artists living in it at the time. Most of them didn’t have national or international renown, living sordid lives, scrambling to find patrons, collaborating on magazines nobody read, staging exhibitions that puzzled the public, and worrying more about ideas than fame or posterity. They were unafraid of experimentation, and willing to be misunderstood. They had little or nothing to do with universities, foundations, or established institutions. If they couldn’t find their way into journals, galleries, and publishing houses, they simply made their own. These artists deliberately opposed the contemporary world, even as they dragged it like a cadaver into the future with them. Their real allegiance was to the idea of the artist as a free agent in the world: they understood that their true audience was other artists; that the goal of art was to redeem a culture always on the brink of forgetting everything; and that most people, rich or poor, will always be far behind their own times.

By the end of its first quarter, the 20th century had already seen what many now consider its most groundbreaking artworks: Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase; Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring and Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire; Joyce’s Ulysses, T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, and Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. A quarter of the way through our own century, do we have a single novel, poem, composition, or work of art that can measure up to these? The answer is nearly always “no”. And if it’s ever “yes”, the examples offered are never really satisfying. Some might suggest the environments of Pierre Huyghe, or the films of Terrence Malick, or Helen DeWitt’s wonderful novel The Last Samurai. But as brilliant as they are, these works simply don’t have the same sense of having revolutionized the medium in ways unimaginable before them. There is far less distance between them and the modernism of Man Ray than there is between Man Ray and the paintings of someone like J. M. W. Turner, a century before him.

When future critics write the annals of our era, I suspect that what will actually strike them most is just how little has happened in our time. Rather than a litany of genius artistic accomplishments, it is much more accurate to see our moment as the height of industrial mass culture’s revenge upon art — a period in which creative industries, academic training, popular taste, assembly-line content production, and distribution technologies have fused into a monolith without qualities. The idea of artists as pioneers and outsiders has given way to a professionalized class within contemporary academic and media institutions. Yet with the arrival of each new digital technology, even these artists risk being taken out of the equation. What’s more, the characteristic experience of art in our time has become divorced from all previous eras in human history: there are few amateur art societies remaining; connoisseurship has been mocked almost out of existence, and patronage reduced to market speculation. For most people, art has next to nothing anymore to do with religious ritual, or even the pursuit of commonality and sociality. Audiences are now individual people behind individual screens — voyeurism is the ruling principle of the digital experience of art.

Everyone knows this: significant portions of these spaces are devoted to discussions about how miserable it is to be there. Even so, what most people seem to want from their media today is the chance to watch other people do things. The most consistent experience of anything resembling art is not happening in galleries, in the pages of journals, at the cinema, or in the concert hall. It consists of watching other people play video games, watching other people make food, watching other people listen to music. Those future historians will likely conclude that life in the first part of the 21st century was something that happened to other people. They will feel pity for the hundreds of millions of human beings whose yearnings were so thoroughly diverted from the world of sense into a state of passive surveillance.

Many of us now spend a majority of our waking lives trapped in a continuous flow of the possibility of experience, instead of experience itself. The revenge upon art is also revenge upon experience, since this is just what we do when we participate in the cacophonic theater of digital spaces — we take revenge upon the difficulty and pain of our experience. The aesthetic of our era is mostly a flight away from art, since art embodies all those things — real sex, death, history, feeling, pain — which we are desperate to escape. Plainly, the modern world has become too complex for us. There is too much news, too much noise, too much action — too much for any one person to handle. Our bodies rebel against their conditions through illness, fatigue, and depression: hence the common sentiment that interacting with serious art is just too difficult, that what’s really needed at the end of the day is mindless, numbing escape. Art must now compete with the universal desire for dissociation.

We have of course been preparing for this escape for a long time. Our anti-art era reached its apex in just the past two or three years, with the arrival of machine-generated versions of visual arts, music, and literature. Whether by accident or design, the makers of these “artificial intelligences” have come close to achieving what many creative industries were tending towards anyways: the abolishment of the artists themselves. The endless scroll is now replete with machine-generated “art”, but so long as the average consumer is seeking to numb their reality, there’s no reason for them to care if what meets them are human- or machine-made images. If our hypothetical future historians are accurate, they will perceive that the dominant tone of our time is anesthetic, since the role of nearly all popular media now is a panacea, meant to assuage an underlying anxiety, but only worsening it in reality.

Anesthetic is a perfect term for a deeper reason, too. Given the meaning of the prefix “an-” (“without” or “lacking”), the word quite literally means “lacking aesthetic” — without feeling or perception. We’re living in a time in which the average consumer’s experience is in tacit collusion with a mass-produced media world that has successfully propagandized on behalf of hollowing out our aesthetic experiences — and which now has the technology to eliminate artists from the production of it. This revenge upon art has so far been successful for two reasons: first, a 20th-century mass culture created by the perfection of major broadcast technologies; and second, the aforementioned conversion of artists to a professionalized class of aspirational elites.

The development of radio and television in the 20th century created the largest interconnected mass culture in history. The values of this monoculture quickly combined with the centralizing and propagandizing dictums of the century’s globe-spanning states. Whether Soviet propaganda, or the leading US television networks, or TIME magazine, or The Times, the idea was the same: whoever reaches and sways the most people wins. Monoculture relied on technologies of mass persuasion, broadcasting from single sources to millions of listeners, readers, and viewers. And the people who experienced this world passed on those same values, creating the newer world of digital information. We on the internet today have inherited this idea that mass culture ought to exist, even though it would seem alien to most times and places in human history. The ideal only exists because of those broadcast technologies, because the point of the game being played through them was to monopolize the maximum amount of airspace and human attention.

The internet, however, is not a single medium, but a fabric of mediums. In its networks one finds broadcast technology but also telephonic and text-based technologies. Social media platforms were able to disrupt the original internet by essentially constructing sociality-themed meta-games in the midst of what was once a decentralized network of libraries, messaging systems, and sites. But where the 20th-century mass culture required many people tuning into a limited range of channels such as radio frequencies, television stations, even cinema screens, social media algorithms curate distinct channels for each user. This traumatic loss of collective experience has been partially substituted by the chaotic “public square” of those platforms. Yet creative industries and tech companies are still based on the old incentives, and have generally monopolized every digital outpost to deliver only their content to huge numbers of people.

Our problem now isn’t a lack of cultural production, but too much of it. So much so that the vast majority of artists simply can’t compete with the tiny number of hugely popular names with the full backing of the media conglomerates. At the empty center of this era of over-production is what the critic W. David Marx has called the “Blank Space” — the name of his recent cultural history of the 21st century. Marx’s Blank Space deals above all with the force of “Poptimism” — a rising idea among many critics that their duty was to advocate for popular commercial products as an antidote to the hipsterism, snobbery, and elitism of the 20th century. As Marx argues, no matter how open-minded these critics thought they were being, the actual result of their rhetoric gave the media and the public carte blanche to reject high-minded art in favor of shallow pop culture, ceding the once-transgressive powers of the avant garde to a resurgent Right-wing often allied with the very tech companies who want to automate away cultural production. This has desiccated creative subcultures and made it harder for critics to get attention for unknown artists, while audiences themselves increasingly reject any attempt to argue for better art as aristocratic arrogance. As the saying goes: “Just let people enjoy things.”

However, part of this resentment against elitist critics also extends to the whole field of modern art itself — something Marx doesn’t consider. The mass culture of the late 20th century — which is what really made the radical art of the early century famous, reducing artists like Picasso and Duchamp to memes and flat cultural icons — continued to harbor at least some of the old oppositional avant-garde sensibility. Even popular artists could be respected for challenging and shocking their audiences. But over time, the paradox was simply too great: if the main imperative is to get as much content out to as many people as possible, then challenging or difficult art can only ever be in conflict with it. This is why Poptimism as an idea has been so deleterious: it preys on the part of the audience which rejects difficulty, which regards the old avant-garde attitude as snobbery, and dislikes critics because critics often tell them that what they like isn’t very good. Over the past few decades, we’ve seen exactly what happens when you combine a global mass-commercial imperative, the hamstringing of serious criticism, and the diffusion of physical countercultures into the internet. The result is the Blank Space: an alarming rate of technological change, ironically counterposed by an absence of novel artistic movements.

As a legible history of the past 25 years, Marx’s book encourages us to imagine something better — to imagine the return of physical subcultures, of serious criticism, and the development of something resembling an avant garde. But this is a forbiddingly difficult thing to do, since the place of artists has shifted so far from what it once was. On the one hand, there is the idea of the artist in popular culture — one which might sometimes contain the old ideal of aesthetic excellence at all costs, yet has for the most part given way to influencers, celebrities, and brand managers. On the other hand, there is the reality of artists within cultural institutions. Look at the blue chip galleries and recipients of huge foundation funds; the majority of “upmarket” authors published by the major houses; the poets who win major literary prizes; the young writers who work their way from unpaid internships to staff jobs; the people who run the arts non-profits. You will find an extreme bias towards upper-middle-class backgrounds and university educations. Looking at the biographies of emerging artist award winners and grant recipients, you might be bewildered by how many of these people have BFAs, MFAs, even PhDs in their area.

This is the professionalization of the artist in our time. It is well known just how difficult it is to get published, or to get one’s work seen, without the right resume: a degree certification, specially curated portfolio, the requisite recommendations. The artist in this professional climate — whether a young composer, painter, poet, or filmmaker — faces an enormous bureaucratic barrier of entry to their field. Their style has to conform to a certain industry expectation, has to fit in with the current understanding of sales trends, and can’t risk offending or upsetting anyone at any step in that process. So, for decades, university programs have sprung up with the intention of training young artists for entry into these careers, in workshops and fine-arts programs designed to maximize their legibility at the expense of idiosyncratic style.

In our current environment, an artist like Man Ray — who turned down a university scholarship, working as a technical illustrator and taking classes at the Ferrer Center, an anarchist day school in New York — would get nowhere. But, of course, artists like Man Ray have never got anywhere in these environments. The early 19th-century Romantics rebelled against the school of Joshua Reynolds; the later Impressionists against the reigning Paris Salons; the fin-de-siècle Vienna Secessionists rebelled against the Association of Austrian Artists; Man Ray, Picasso, Duchamp and other avant-gardists rebelled against the ossified remains of those previous revolutionary styles. Today’s young creatives may want to think of themselves as a crusading vanguard, particularly regarding social justice causes, but, more often than not, they are themselves the producers of the stuffy bourgeois academic style which all great modern art movements have defined themselves by rejecting.

This state of affairs has only contributed to the suspicion that today’s creatives are hustlers and grifters making risk-free art. Where former eras regarded them as confusing freaks, even exiles, the public now sees them as poseurs and snobs. The undifferentiated style of these artists’ exhibitions, novels, poems, and compositions only reinforces the sense that their only audience is other professionals and academics. At the same time, as hemorrhaging industries concentrate more and more on sure-fire market successes, the professionalized caste is kept on life support solely by grants, residencies, foundations, and legacy media attention. Potential audiences drift further towards mass-produced slop and digital numbness, yet these artists still sand away every bit of risk, experiment, or novelty to make it in the shrinking creative industries. There is very little room in this equation for the creation of new artistic movements — and little incentive for anyone to want one.

So what is to be done about this? Well — many things. The first is to be clear about the situation, no matter how depressing. For the time being, the majority of the public is too distracted, numbed-out, and tech-addicted to respond to much art. Still, this is only a despairing thing from the point of view of that 20th-century monoculture. For most of human history, the production of culture was meant to exalt God, or give prestige to the ruling aristocracy. In the wake of the Romantics and modernists, the highest value became the creation of great art as the ultimate mode of human experience. When this becomes the ideal pursuit, even at a social cost, and the artist is understood as an essential outsider, public disinterest becomes the norm; it even becomes a sign of health. One of Man Ray’s consistent refrains was that whenever he noticed his work confusing someone, he knew he was really on to something.

We also have to admit that the current academic style is moribund. My generation — made up of young Millennials and elder Zoomers — has yet to produce a truly great novelist, poet, composer, or painter. And that is because too many have given up the time and energy that should have gone to their true education in formal history, to pursue professionalized academic tracks promising elite approval. As Marx pointed out, these careerist industries have left the old transgressive spirit of the avant garde to be subsumed by trolls and reactionary Right-wingers, who are themselves nearly incapable of producing art, their transgressions limited to stepping on liberal social norms and indulging in half-ironic bigotry. Not that progressives have fared much better: the last two decades of social justice politics produced no great art, with proponents largely choosing empty pieties over practical liberatory politics. Once elites figured out how to use the language of those movements, they quickly adopted it to police established class boundaries in the media, and plenty of artists adapted to the situation immediately.

What is clear is the need for secession. The need for greater numbers of serious artists, writers, musicians, and filmmakers who exist outside of the academy, legacy media institutions, and the major creative industries. Artists who create their own smaller institutions, their own laboratories, their own publications, their own exhibitions — all with the clear intention of avoiding trends, embracing experimental collaboration, and rejecting the need for a large audience whatsoever. At the beginning, the only audience should be other artists. Artists need spaces outside the confines of the internet, even outside the confines of society. Yet much of what goes on now, in the burgeoning scenes of New York, London, or Paris, are only small magazines, artsy parties, and showings with an eye towards sexy contemporary issues. A lot of it only happens in conjunction with small presses, or on Substack.

These people certainly have the great avant-garde artists in mind — they yearn for the days of bohemia, for Paris between the wars, or the Künstlerhaus in Vienna. But so far, their attempts to forge new art scenes have been too much scene, and too little art. The point there is less to experiment and envision some genuinely new movement, and more to imitate the romantic social lives of older artists. Until these scenes take the collaborative process of art-making and art-theorizing as seriously as they do their parties and online publications, they will be transitory. What’s more, artists need to be far more sincere about mixing with different kinds of creatives. One of the most remarkable things about interwar Paris was just how many kinds of people mixed together — aristocrats, socialites, commercial artists, designers, filmmakers, painters, playwrights, poets. They didn’t segregate themselves by medium, only by the groups they’d dedicated themselves to (and even then those boundaries could be quite porous). Judgment and taste were the sole currency. Artists who didn’t measure up to their standards were quickly dismissed as kitsch-mongers. Today we mischaracterize this posture as elitist — but it is only elitist if it comes from an actual powerful elite. For artistic movements, strict standards are self-preservation, the only thing with any chance of revitalizing a calcified aesthetic culture.

The art of the future is not going to come from our current institutions and academies. Yet neither is it going to be purely Romantic, or purely modernist. It will have to emerge from the technical mastery of all forms that came before it. Artists will have to spend far less time seeking facile “personal expression” and more time practicing old-fashioned methods, understanding them inside and out — which is the only real way to imagine something beyond them. Only an intimate understanding of the history of an artform can really respond to the world as it is now, a world which has tried to take its revenge upon art by robbing artists of their role in society, and drowning the masses in assembly-line slop.

The new contemporary art will have to be part evangelism and part theater; the artists will have to be unforgiving preachers of the gospel of aesthetic excellence. They will have to be stringent in their commitment to experimentation and their rejection of the current style. For the sake of real creative freedom, they will have to reject positioning and political signaling (though this hardly means rejecting politics itself). What is needed, in short, is a theory of contemporary art which aspires once again to shock its audience, when it finds it — not merely to transgress against social norms, rather to shock people back into reality, back into the stream of experience. The role of the artist in the anti-art era will be the person who sees the world as it is — numbed-out, anxious, resentful, overwhelmed, half-asleep — and tries to wake it back up again, by whatever means necessary.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe