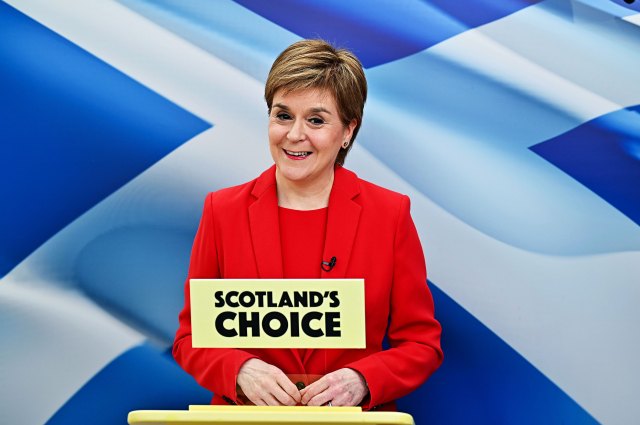

Nairn was no false prophet (Jeff J Mitchell – WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Nicola Sturgeon has exited the stage, but the threat of Scottish independence has not. Whatever the triumphalism in London over the First Minister’s resignation yesterday, the idea that the secession crisis has ended is absurd. For the time being, the grim truth is that neither Scottish nationalism nor British unionism is strong enough to triumph — not because of some personality problem, but because of deep, structural weaknesses on both sides.

Today, both secessionism and unionism feed off the other’s incoherence. Sturgeon’s press conference in Edinburgh compellingly proved this: she described her decision in ways that made it sound as if she were some kind of martyr. Under her leadership, she said, the cause of Scottish nationalism had suffered because it had become caught up in the irrational partisanship of her opponents, who had grown to dislike her so much that they could no longer judge Scottish independence on its own merits. She was, she intimated, sacrificing herself in the hope that a new leader would be able to bring more people into the tent of Scottish nationalism. Unionists should not be complacent about this prospect — she may actually be correct — but the structural problem for Scottish nationalism is not the prejudice of its opponents, but the failings of its own offer.

Brexit has made Scottish independence a far more complicated prospect than it was before. It is now possible that we will look back on the referendum in 2014 as the moment Scottish independence made the most sense. Fair or not, Brexit means that Scotland cannot dilute the dominating reality of England simply by leaving the union and joining the rump UK in a wider EU. If anything, Brexit has made England’s hulking presence next to Scotland even more pronounced, while demanding answers from the SNP that it does not seem ready or able to provide. What happens at the border with England? Will Scotland introduce the euro? Will Holyrood accept common European debts? Will it rejoin the Common Fisheries Policy? For the SNP, Brexit has turned out to be both the casus belli for its second push for independence and a strategic disaster. The best thing that could happen to Scottish nationalism would be for Britain to rejoin the European Union.

For unionists, however, Brexit might be an unexpected weapon in their constitutional arsenal, but it is one whose very existence is a reminder of the union’s inherent Englishness. Today, it is impossible to escape the reality that the UK has ceased to function in any meaningful sense as a unified British state; it now operates as an incoherent and imbalanced union of separate entities whose English character has not been softened by devolution, but incalculably sharpened. The fact is, the more Holyrood dominates Scotland’s national life, the more English the actual national parliament in Westminster becomes. This is a hole in the national barrel, draining the legitimacy of parliament and in time the union itself. The irony, then, is that just as Brexit acts as both an irritant and a salve to the threat of Scottish independence, devolution itself is a prime source of the union’s instability, the unbridgeable fault line in the body politic which no-one in Westminster is prepared to confront.

Watching Sturgeon’s resignation, I was reminded of the late Tom Nairn, the great academic pin-up of Scottish nationalism whose book The Break-up of Britain argued that the British state was destined to collapse like the Hapsburg, Tsarist or Prussian regimes of the 19th and early 20th centuries. “It is a basically indefensible and unadaptable relic, not a modern state,” wrote Nairn. “The only useful kind of speculation has assumed a geriatric odour: a motorised wheelchair and a decent funeral seem to have become the actual horizons of the Eighties.” Nairn’s book was published in 1977 and yet the geriatric old relic endures, still supported by half of Scottish voters, despite Brexit and the political crises in Westminster that have followed.

Yet Nairn cannot be dismissed as a false prophet. As a political force, Scottish Nationalism has been transformed since 1977. The SNP is now the dominant force in Scottish politics, with independence supported by almost half the population and most of the young. As a result, Britain is easily the most fragile power in western Europe, or indeed the wider Western alliance. Almost no other country — apart from Canada or Spain — is as close to breaking apart.

Nairn was also right to argue in the 2002 edition of his book, when devolution was being hailed as a great reform which would permanently obstruct the demand for independence, that the British state remained structurally unstable. “A new tide seeking real independence is forming itself beneath the facade of Blairism,” he wrote. “It will rise into the spaces left by New Labour’s collapse, and by the increasing misfortunes of the old Union state.” Thirteen years later, the SNP expelled Labour from Scotland, winning every seat but three.

Nairn, in my view, was right to see long-term structural challenges to the British state, but wrong to believe that this made it uniquely outdated, or somehow destined to collapse. The fact that after eight years as First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon has resigned, still unable to answer how Scottish independence will be enacted, is testament to the inherent challenges of secession, not just continuity.

When I asked Nairn a few years ago about the challenge Brexit posed to Scottish nationalism, he was thoughtful and reflective, arguing that it changed the type of relationship an independent Scotland would have with the UK after the latter’s inevitable collapse. In his last interview before he died, Nairn argued that what would eventually replace Britain was still being worked out. “We’re trying to replace Great Britain… with something else, but what that is, there is no ready and living example of it to which we can turn. We have to make it up as we go along, because there is nothing else.”

In this he was right, but the truth is both sides are making it up as they go along. None of us have been here; everything is new. Unionism has yet to offer coherent answers to the problems posed by devolution to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland but not England; Brexiteers have yet to offer coherent answers to the problem of Northern Ireland and its border with the Republic; and Scottish nationalists have yet to offer coherent answers to the problem of seceding from Britain after Britain has seceded from Europe. Nicola Sturgeon departs as First Minister of Scotland having failed to find them. But her opponents should not crow, for they have not succeeded in this task either.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe