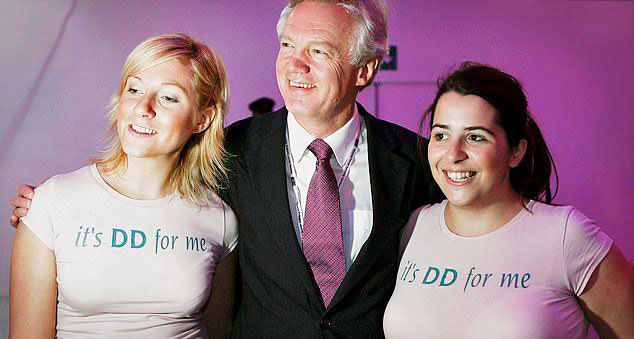

Mr DD (Getty)

With MPs reassembling after their February break, the great Boris Johnson Leadership Melodrama will soon be back in the headlines. For the time being, at least, the Prime Minister survives, bloodied but not yet fatally wounded by that tumultuous encounter with a birthday cake. Yet even if he does cling onto power, everybody knows now that Boris is mortal.

The polls tell the story. Prime Ministers with a disapproval rating of 70% rarely last long. Nobody defies gravity forever. Margaret Thatcher didn’t; nor did Tony Blair, despite winning three elections. Johnson has won only one. And the next test is not far away. On 5 May voters across the country will go to the polls in the local elections. A terrible set of results, and more letters of no-confidence will surely flood in. For Rishi Sunak, Liz Truss and their rivals, the prize must seem so tantalisingly close…

And yet, and yet. Political history is littered with examples of potential leaders who struck too soon or waited too long, future England captains whose moment never came. Nobody remembers the R. A. Butler governments of the late Fifties and early Sixties, because they never happened. A decade later, Roy Jenkins sharpened the knife, raised it high about his head and prepared to plunge it deep into Harold Wilson’s back… but the blow never fell. And a decade after that, everybody knew Tony Benn was going to become Labour leader one day — but he never did.

The list goes on. Willie Whitelaw delayed and delayed, loyal to the last to the beleaguered Ted Heath, and then found himself overtaken by, of all things, a woman. Michael Heseltine timed his deadly attack on Margaret Thatcher to perfection, only to discover that many of his fellow Conservative MPs would never forgive him for it.

Kenneth Clarke won three separate parliamentary ballots in three different Tory leadership contests, yet never wore the crown. David Davis arrived at the Conservative conference as a runaway favourite with two busty women in T-shirts reading “It’s DD for me”, only to find that the party faithful preferred a smooth-talking shepherd’s-hut enthusiast instead. Even Boris Johnson’s first leadership bid exploded on the launch pad, sabotaged by his chief engineer.

And then there’s the most disastrous campaign of all, the Labour moderates’ risible attempt to unseat Jeremy Corbyn in the summer of 2016. “Angela is a star in the Labour firmament. She will be at my right hand throughout this contest and if I am successful, Angela will be alongside me as my right-hand woman.” The words of the future Labour leader Owen Smith, talking about his erstwhile rival Angela Eagle. That was just five-and-a-half years ago. Dame Angela is still there somewhere, lurking unnoticed on the backbenches. But poor Smith isn’t even an MP.

It would be nice to claim there’s a clever formula for success, or to tease out some immutable “lessons from history”, but that would be disingenuous. There’s no formula. Indeed, the joy of political leadership campaigns is that nobody can quite predict the strange chemistry that makes a winner, the peculiar combination of luck and personality, the unforeseeable, unrepeatable point when man (or woman) meets moment.

Take Labour’s Roy Jenkins, the embodiment of metropolitan citizen-of-the-world liberalism, whose admirers often describe him as one of the best Prime Ministers Britain never had. In the spring of 1968, the only question was not if, but when. Following the humiliating devaluation of the pound a few months earlier, the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, seemed crippled beyond recovery. The public had tired of his endless slipperiness, and as a smart and urbane crisis Chancellor — Rishi Sunak parallel alert! — Jenkins seemed the only plausible successor.

On the Labour benches Jenkins commanded what he called “a dedicated group of commandos, waiting as it were with their faces blackened for the opportunity to launch a Dieppe raid against the forces of opportunism”. Their leaders reported that they had assembled an elaborate system of ‘dissident cells’ comprising more than a hundred supporters, as well as an ‘inner group’ who would co-ordinate the revolt. At a secret meeting on 17 June the chief plotters even produced a definitive list of some 120 potential rebels. All they needed was the signal to strike.

It never came. A couple of weeks later, Jenkins told them to hold off for the time being. The premiership was so close — but he “did not want to be implicated in actually launching an action”. A convicted assassin, he believed, would never wear the crown: “I will never be caught with a dagger in my hand unless it is already smoking with my enemy’s blood”.

So Jenkins waited, and waited… and the moment passed. Wilson stayed on at Number 10 and Labour lost the next election. Gradually, almost imperceptibly, Jenkins lost his sheen. He went from tomorrow’s man to yesterday’s, without ever having been today’s. By the time Wilson retired in the spring of 1976, Jenkins’s chance had vanished. He had fallen out with the party’s Left wing over Europe, but there was a palpable sense, too, that he lacked the killer instinct.

Later, in his memoirs, Jenkins fell back on the excuse that he had never been ambitious enough, a clever way of complimenting himself for his own failure. But some of his supporters told a different story. “Roy was too ambitious, not insufficiently ambitious,” wrote his friend David Marquand. “He never thought it was the right moment; he always thought it was too risky”. The stakes were too high; he was paralysed by the fear of missing out. I wonder if, one day, Sunak’s friends will tell a similar story?

What of Jenkins’s insistence that the assassin never wins the ultimate prize? Well, there’s always the lesson of Heseltine in 1990. But such a flamboyant showman would have been deeply distrusted by many Tory MPs even if he’d never lifted a finger against Margaret Thatcher. And there are plenty of telling examples of political hitmen who made it all the way. Stanley Baldwin, instrumental in terminating Austen Chamberlain’s leadership in 1922, became Tory leader himself two years later. And Harold Macmillan succeeded Anthony Eden in 1957 precisely because many Tory MPs thought that by knifing Eden in the back, he had showed the cold, single-minded ruthlessness that Rab Butler lacked.

Then there’s the best-known political assassin of all, an object lesson in pitiless opportunism. Margaret Thatcher had spent the first four years of the Seventies nodding and smiling at Ted Heath’s policy U-turns. Not once had she whispered a word of dissent. And when, after the second general election of 1974, she announced that she was challenging him for the leadership, nobody seriously thought she would win.

The story goes that when, as a courtesy, Thatcher visited Heath to warn him of her intentions, he said coldly: “You’ll lose.” The Conservative parliamentary party, agreed his old rival Enoch Powell, “wouldn’t put up with those hats and that accent”. Even Mrs Thatcher’s family thought she was wasting her time. “You must be out of your mind,” remarked her husband Denis, not entirely supportively. “You haven’t got a hope.”

Yet as it turned out, Thatcher beat Heath by 130 votes to 119. (“A black day,” declared another of his old rivals, Reginald Maudling.) And now the strange magic of leadership contests took effect. With Heath gone, four new contenders, notably his lieutenant Willie Whitelaw, threw their hats into the ring. But it was too late; all the momentum lay with Thatcher. As the Telegraph remarked, it looked as if “a whole herd of fainthearts left it to a courageous and able woman to topple a formidable leader” and then “ganged up to deny her her just reward”. When the second ballot was held a week later, she stormed to victory. “My God!” exclaimed one Tory vice-chairman when the news came through. “The bitch has won!”

The other great canard about leadership elections is that you should keep an eye on the dark horse, with John Major’s victory in 1990 as Exhibit A. But was Major such a dark horse? He was, after all, Chancellor of the Exchequer, having just served a short stint as Foreign Secretary. It’s true that if the leadership election had been held a year or two earlier, he wouldn’t have stood a chance. But Major had timed his run to perfection, his victory a perfect example of how, in politics, you make your own luck. It would have been easy for him to waver in 1990: to bide his time and sit this one out. But he calculated, quite rightly, that he would never have a better chance. With cool, understated efficiency, he took it.

In reality, most dark horses never come remotely close to winning, and many soon relapse into utter obscurity. Who now recalls Peter Lilley’s leadership pitch in 1997? How many people look back on Michael Ancram as the great lost leader of 2001? Is there, perhaps, some parallel world in which Stephen Crabb faced Liam Fox in the final round of the Tory contest in 2016? Can there really be a universe where Mark Harper battled Esther McVey for the crown three years later?

Yet all of these people, presumably, must have imagined the pieces slotting into place: their colleagues marvelling at their unexpected talents, the other contenders falling away, the momentum sweeping them towards that historic audience at Buckingham Palace. Alas, it almost never works out that way. If you enter the contest as an outsider, you’re probably doomed before you start, because most MPs like backing winners.

A good example is one of the most colourful dark horses in modern political history, the hard-drinking, grammar-school-smiting Labour intellectual Tony Crosland. When Wilson resigned in 1976, Crosland fancied his chances. He looked at his rivals. Jim Callaghan, the favourite: too old. Michael Foot: too Left-wing. Roy Jenkins: too Right-wing. Denis Healey: too arrogant. Tony Benn: too mad. And it all seemed so straightforward. One by one the others would blow up, and Crosland would come through the middle.

So the future Prime Minister summoned his protégé, Roy Hattersley, who would surely play a key role in the victorious campaign. They got straight down to business. The most important thing, Crosland said, was to get a “decent vote” in the first ballot, and build strength from there. “I take it you’ll vote for me.”

Silence. Then, at last, Hattersley confessed. He didn’t want to waste his vote, and had already promised to back Callaghan. Crosland couldn’t believe his ears. It was all falling apart, and the campaign had barely started. “You’ll not vote for me?” he said. “Then fuck off.”

Crosland finished dead last in the 1976 leadership election, with just 19 votes. And the winner? Callaghan, just as everybody had predicted. Dark horses aren’t dark horses by accident. Favourites are favourites for a reason.

So are there no lessons at all for Rishi Sunak and Liz Truss — or for Jeremy Hunt, Penny Mordaunt, Tom Tugendhat and the host of other putative dark horses? Well, here are a few thoughts. Most politicians only get one chance. Miss your moment, and it never comes again. Courage is usually more admirable — and more effective — than caution. If you do stand, don’t say anything stupid. Ideally, don’t say anything at all.

None of this is very helpful, I know — not least because there are so many obvious exceptions. So to finish, here’s one ironclad rule of leadership contests, which may not be what the current hopefuls want to hear.

Really, honestly, it would be better to lose. Losers always have more fun. Just ask yourself: would Roy Jenkins have been able to enjoy quite so many agreeable three-course dinners if he’d been Prime Minister? Or would he rather have been defending the Government’s policy on salmonella? Would Denis Healey have been free to appear on TV with Roger Moore and Dame Edna Everage? Or would he rather have been at a meeting in Frankfurt with Helmut Kohl? Would Ken Clarke have been happier organising a junior ministerial appointment for John Bercow, or smoking his fifth cigar of the night in some West End jazz club?

For this is the great unspoken truth about leadership contests: it’s a competition to see who’s going to be the most despised person in the country in a couple of years’ time. Yes, you get to have your picture on the Downing Street stairs, just along from Gordon Brown and Theresa May. But as they would surely tell you, being Prime Minister is awful. Everything goes wrong, and everybody hates you. So instead of agonising about when to declare and what to say, just don’t do it. You’ll have a much happier life if you stay out, and the country will thank you for it.

Here endeth the lesson. Liz, Rishi: don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe