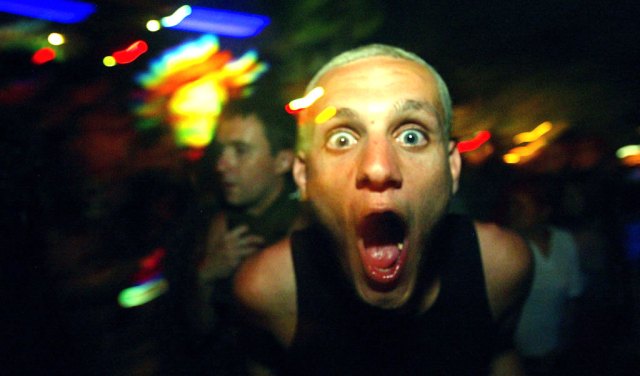

A raver in Thailand. (Photo by Paula Bronstein/Getty Images)

The nightclubs opened again on Sunday night, with queues around the block. I was not there, but while middle age has done for my former love of sweaty, expensive late nights, I’ve spent my share of evenings fidgeting in club queues.

I was born the year Thatcher came to power, and came of age just as the rave scene began to be pried loose from illegal parties in fields and sweaty, underground warehouses. By the time I turned 18, the countercultural hedonism of rave culture was a regulated multi-million-pound industry. Even so, clubbing felt subversive: a form of self-expression where social norms could be dissolved in a bath of pure hedonism, shorn of stuffy rules and social norms.

Hearing the bass get louder as you approached the entrance, and the way the air became a warm, rich fug of dry ice, hormones and ear-bursting noise. The spark of sexual tension, the illicit substances, the sheer extravagance all felt thrilling.

But with the cynicism of my now-wizened age, I’ve come to believe that nightclubs have replaced their subversiveness with a sort of cuddly fascism. I’m not talking jackboots-and-flags fash, of course; but instead about how the absolute hedonism and self-expression of a nightclub needs a single point of authoritarian control — the DJ. Usually enthroned in an elevated position that resembles a dais or altar, everyone surrenders to this monarch of the decks, while order is kept at the margins by his unaccountable enforcers: the bouncers.

It’s a note-perfect representation, in other words, for the way an individualistic society seems to combine the pursuit of freedom with a drift toward authoritarian governance. Perhaps unsurprisingly, studies suggest the generation that came of age after me — just as clubbing went mainstream — is the most authoritarian generation alive in Britain today. One 2019 report showed 35% of under-35s supported having the army run the country, compared to just 15% of over-65s. And just 75% thought democracy was a good way to run a nation, down from 93% of over-65s.

But if the hedonistic autocracy of a nightclub is the perfect metaphor for an emerging millennial authoritarianism, so too is the crowd: a mass of people united in the shared thrill of the music, yet also atomised, every dance unique. And indeed, a study released last week by the think tank Onward reported the most authoritarian generation is also the loneliest.

According to the study, 22% of under-35s say they have one or no close friends. This proportion has trebled over the last decade, while the proportion with four or more close friends fell from 60% to 40% over the same period.

I’m not suggesting that growing up clubbing somehow caused a generation to become lonely or authoritarian. But we’re all, to a great extent, what our parents made us; and the millennials, children of the boomers, were raised to express themselves. We can hardly blame them for doing so — or for accepting the trade-offs. And even if self-expression inadvertently makes us lonely, there’s always Big Tech to help. This industry is now rushing to fill the gap, with apps to help you find friends as well as a partner.

Will this work? Loyalty and affinity have their own arithmetic, and it’s not very amenable to individual control — or computer algorithms. I’ve drifted through numerous social scenes, careers and geographies over the last two decades; people who’ve become and stayed friends over that time are often not those I might have clicked as a “match” on some website.

Besides, contrary to the stereotype that sees younger people as so self-absorbed they don’t want friends they can’t choose, Onward’s report questions the idea that young people are selfish. For example, under-35s were twice as likely as older generations to look in on vulnerable or elderly neighbours on a regular basis during the pandemic.

Nor is it purely a matter of spending too much time on social media. While another easy “young people nowadays” stereotype paints them all as too Very Online to socialise in the real world, it seems that only 25-34s now conduct their social lives mainly online. For this group, 42% agree that “I have more friends online than I do in real life”, while only 25% disagree.

This lonely, very online demographic, though, has been heavily represented in political unrest over the pandemic. Indeed, as lockdown after lockdown has rolled out, I’ve come to suspect a link between those shuttered nightclubs and flourishing mass demonstrations.

I’ve argued elsewhere that pandemic-era protest is less directly about politics than self-expression: a rave-like experience, ordered by a generalised, emotive cause without clear links to any specific policy outcome. The expressive quality of this phenomenon was richly illustrated by the protest against lockdown that took place to mark the end of restrictions. It remains to be seen whether this energy that migrated from clubland to street politics will go quietly back to its box now that dancing is permitted again.

I dare say those millennials who’ve done well over the last two decades will be happy to see that happen. The older edge of this generation is reaching positions of political influence now, and will likely be happy to help roll out legal, cultural and financial infrastructure for the authoritarian hedonism they themselves have largely evaded. Who cares about a little more state control, if that’s the price of expressing yourself with an evening dancing? No wonder the kids are being offered a return to unrestricted clubland partying — but only in exchange for willingness to be vaccinated, and perhaps to show a vaccine passport.

And perhaps for some this will be enough. When the BBC filmed elated clubbers at Fibre in Leeds on Monday, the watchwords were “friends” and “freedom”: that paradoxical cocktail of individualism, mass participation and hedonism that only a nightclub delivers. “We’ve been blamed for the spread of the Covid”, said one twentysomething woman, “and it’s just nice to get freedom”. But others may find the buzz wears off.

For Covid abruptly switched off most of the compensations offered to those millennials who didn’t do so well in an increasingly brutal economic race, that’s engulfed everyone my age and younger — and whose sharp strictures are helping to drive an epidemic of loneliness. Its contours are well-documented. Home ownership was 53% in the early 1980s, for example, in outer London — but by 2018 it was just 16%. A twentysomething working full-time on minimum wage would have to pay at least 71% of their wages even to rent a one-bedroom flat anywhere in the UK.

It’s hard to picture settling down in those conditions; and indeed, the age of first marriage has been rising steadily for years. Onward’s study suggests many feel too overworked and precarious even to build neighbourly relations or local friendships. This generation, then, may not just be lonely and liquid by choice but also by circumstance.

Against that backdrop, perhaps the appeal of individualistic hedonism isn’t so startling after all. Clubland offers a dream of freedom and self-expression, albeit with little of enduring value to go home to in the morning. But if your home is a shoebox owned by a private equity firm, why would you not want to have a good time?

If this seems bleak, there is some hope that Gen-Z will turn the tide. For this generation, Onward suggest, rejects the internet’s offer of a lonely existence: under-24s are more likely to disagree than to agree with the statement “socialising online is better than socialising in-person”. And in keeping with this turn away from hyper-mediated mass loneliness, there’s evidence that Gen-Z is also backing away from the kind of mass hedonism of clubland; Gen-Z drinks less, has less sex and is more interested in getting good grades and time with family and close friends than getting blitzed and dancing till 4am.

The more prescient members of Gen-Z, then, seem already to have grasped that the clubland no longer offers a promising social metaphor. They’re adjusting their party (and life) plans for a different mode. The question ahead of us is what becomes of the millennials now sliding, in my footsteps, into middle age.

Banks and private equity firms are snapping up rental housing, and investing in build-to-rent new construction. This spate of investment implies a financial sector confident in having a captive market for private rental housing for a long time. The Dalston warehouses where I queued on Friday nights in the noughties have long since been converted to luxury apartments for the millennials who did well over the last two decades: the coming generation with cultural influence, OBEs and budgets.

And because freedom has been good to them, we can expect them to go on pushing the authoritarian-tinged policies of hedonism and atomisation that delivered freedom (and fond memories of clubbing) with few obvious downsides, until they were ready to buy a house and have kids. But for the also-rans, the ones now missing the boat for starting families, the eternal renters, the chronic gig-workers with seemingly insuperable student debt, the “freedom” to get mashed for an evening may not feel like compensation for long.

In clubland, if you lose track of your friends and dance to the bitter end, you’ll see the lights come on to reveal a dance floor in its true colours: shabby, lonely, devoid of fun. More importantly, partying may not pacify Britain’s lonely and increasingly pessimistic young people forever — with or without a vaccine passport. In such a scenario, expect a bitter political comedown.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe