If you can't escape home, you can at least escape into a book. Credit: LOIC VENANCE/AFP via Getty Images

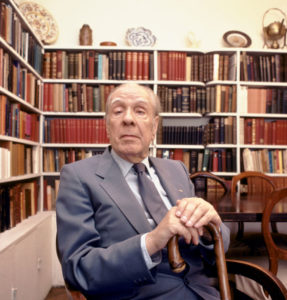

Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, by Jorge Luis Borges

Recommended by John Gray

This short story tells of the discovery of an encyclopaedia describing an imaginary world that has been invented by a secret society. In Tlon there is only one intellectual discipline: psychology. Physical objects are ideas in the mind; only the floating world of impressions and notions exists. Yet these insubstantial ideas have the power to invade the realm of matter.

In a postscript, Borges records how, after the discovery of this encyclopaedia, people began to find small and extremely heavy cones, “made from a metal that is not of this world”. The “primitive language” of Tlon found its way into schools, where a make-believe history was taught and only a concocted past remained. The imagined universe of Tlon disintegrated the human world.

Nearly everyone in lockdown has been struck by a sense of unreality. It is not only the empty cities that seem phantasmagorical. So, too, do the lives we led before the pandemic. If we long to return to the way we used to live, we also suspect that this previous life was a fantasy.

In pre-lockdown reality, other species were becoming extinct at a rate unprecedented for tens of millions of years. The climate was becoming violently unstable. Yet these realities did not disturb the world dreamt up in the human mind. It came to be believed that humans lived in a new era — the Anthropocene — in which they had mastered the natural world.

Like Tlon, the Anthropocene was a figment of the imagination. Springing from living relics of wilderness sold off to be eaten, the virus has disrupted that dream. While it was dreaming, humankind was desolating the planet. Now the dream has dissipated, we find ourselves in a world that seems too strange to be real. But it is in this world in which we must learn to live, with the virus.

The Man Who Planted Trees, by Jean Giono

Recommended by Polly Mackenzie

One of the great lessons of this crisis will be that we need to make more decisions for the long term. We have to prepare not for what we need now, but for what we will need in the future. To help us absorb this lesson, there is one parable I think we should all read, and especially everyone working in politics: The Man Who Planted Trees, by Jean Giono.

It tells the story of a shepherd called Elzéard Bouffier, who Giono meets in a wind-swept, desolate valley in Provence in 1910. He watches Elzéard sorting and then planting hundreds of acorns as he walks through the wilderness. Giono returns after surviving the first world war to find the valley is starting to bloom into health, with saplings everywhere. The world has torn itself to pieces but one man’s gesture of hope has created new life where there was none. And Elzéard continues to plant, even after the forest is mature and the valley prosperous.

This modern edition has an introduction by Michael Morpurgo

Elzeard teaches us that life and hope can come from the most desolate circumstances. He teaches us that one man or woman’s choices can make an endless difference. He teaches us that small gestures can be transformative, if you give them time, and don’t give up.

The story is short but it covers decades of history. You have to, if you’re writing about trees. It’s just one of those things about them, as I had to explain to my son when he planted a pear seed in the middle of the lawn last week. They take a long time to grow. There will not be pears for dinner. You do not plant trees for today, or for yourself.

So look at the trees in your park or street as you go for your daily constitutional. Wonder who planted them. Give thanks. And then wonder what gift you can give to someone who comes twenty, or fifty, or a hundred years from now.

The Expert System’s Brother, by Adrian Tchaikovsky

Recommended by Chris Deerin

There’s something about the lockdown — the unshakeable murmur of anxiety, the throb of genuine distress, the sudden unknowability of the future — that has left me temporarily unable to cope with, and less tolerant of, much literary fiction. I need escape, and plot, and preferably humour. Stories in which things happen. That don’t overstay their welcome. That get me out the door.

I’m largely finding my solace in science fiction: world-building and otherness provides a place to liberate oneself, to get lost, to be dazzled.

Adrian Tchaikovsky is among modern sci-fi’s biggest plasma guns. I came to him relatively late, when his wondrous, anthropomorphic tale of space-spider evolution, Children of Time, deservedly won the 2016 Arthur C Clarke award.

I’ve just finished one of his slighter works, a 170-page novella called The Expert System’s Brother, published in 2018 but highly germane to the current madness. Humanity endures a reduced, agrarian lifestyle, living in small villages run by wise elders. The twist, though: these elders seem to be cyborgs.

Don’t underestimate the power of a good sci-fi novel

As the story unfolds it becomes clear that a lost history — of forgotten science and technology and space travel — is being excavated, both figuratively and literally. In his search for meaning, 16-year-old Handry, the central character, is therefore confronted with two possible futures for his kind.

How much power and autonomy should technology be given? What is the role and purpose of human agency? How can difference and prejudice be overcome? Can tradition be beaten? Along the way, our protagonist encounters a figure who offers messianic certainty — and Handry struggles to hold on to scepticism and doubt, those most essential human qualities.

As we emerge from the Coronavirus plague and recalibrate our society, these questions — as old as the hills but utterly of the moment — will similarly confront us. The Expert System’s Brother is a useful primer, a philosophical stimulant, and a cracking read.

The Diary of a Nobody, by George and Weedon Grossmith

Recommended by Tom Holland

On Easter Sunday, I rose very early with my wife, and walked through an empty London. To see the banks of the Thames, the City and the West End all still and silent was as eerie an experience as any we have ever had. Looking towards Primrose Hill, wherein H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds the Martians set up their base and then die of flu, it was hard not to feel that we had strayed into the world of the novel. “Those who have only seen London veiled in her sombre robes of smoke can scarcely imagine the naked clearness and beauty of the silent wilderness of houses.”

Which is why, as my lockdown read, I would recommend a novella published five years before The War of the Worlds, and which, although likewise set in late Victorian London, could not be more utterly, more joyously different.

“Why should I not publish my diary? I have often seen reminiscences of people I have never even heard of, and I fail to see — because I do not happen to be a ‘Somebody’ — why my diary should not be interesting.” So begins The Diary of a Nobody, the chronicle of the spectacularly unspectacular life of Mr. Charles Pooter, a City clerk.

Illustrations by Weedon Grossmith

He paints a bath; he despairs of his raffish son; he attends a ball at the Mansion House. Nothing much more than that happens. There are certainly no murderous tripods. Yet it is the easiest, most enjoyable read. “The funniest book in the world,” Evelyn Waugh called it — and he did not exaggerate. As a distraction from the strange and unsettling times in which we live, I cannot think of a better recommendation than this great celebration of the normal and the utterly conventional.

Oh, and the illustrations are wonderful as well…

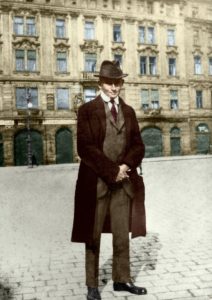

The Burrow, by Franz Kafka

Recommended by Jenny McCartney

The experience of ‘lockdown’ has — for many of us — shrunk the world to the confines of our homes, save for the occasional government-approved excursion. With sufficient vigilance, we are encouraged to think it may be possible to keep the viral foe at bay. Meanwhile we contemplate our domestic grocery stores with fluctuating concern or satisfaction.

Which is why, while stuck indoors, you should read Franz Kafka’s short story ‘The Burrow’. Do not, however, approach this story if your sanity already feels precarious.

‘The Burrow’ is narrated in the voice of a large burrowing animal — a carnivorous, mole-like creature, we intuit, although the exact species is never declared. This creature is obsessively concerned with the security of its home and larder, into which it has poured a vast amount of labour and strategy over the years. Like any stockpiler, it gloats over its supplies, which it hoards in a section called the Castle Keep: “Consequently I can divide up my stores, walk about among them, play with them, enjoy their plenty and their various smells, and reckon up exactly how much they represent.”

The animal has acute hearing and smell, which enable it to detect the approach of enemies — or false alarms — at a great distance. Such perceived threats trigger enormous worry, and a degree of precautionary plotting that verges on madness. The story is a unique portrait of a paranoid mind, and yet — without any objective means by which to assess the external threat — the reader cannot judge whether or not the paranoia is partly justified.

Kafka, a German-speaking Jew in Prague, was keenly aware of both the lurking external menace of anti-Semitism, and the invasive horror of a germ: the tuberculosis that killed him. Yet only his peculiar genius could have nosed out such a means to let anxiety speak.

All good writers try to shrug on other skins, to inhabit other characters. But Kafka dares to cross into other species, to shrug on skins that are not human, and somehow triumphs. Although this creature talks, it is not human: its tunnelled world reeks of earth and instinct and the atavistic consumption of lesser animals, or ‘small fry’. And yet we recognise its voice.

I have read ‘The Burrow’ many times, and it still astounds me. To come to it now, however, is to experience the height of its bizarre spell. For we are communally closer to its claustrophobic, uneasy mindset, in this strange period of history, than most of us have ever been before — and, hopefully, will ever be again.

The Clothes They Stood Up In, by Alan Bennett

Recommended by Simon Evans

To the Billy Liar in all of us, a sudden lurching change in reality such as that effected by Lockdown triggers a slew of rough parallels drawn from fiction, myth and movies. Everything from Planet of the Apes to 28 Days Later to The Truman Show have suggested themselves as templates for our new situation. Or in Hove, Planet of the Gulls.

But the short fiction that has helped me to understand the potential of this moment is that of the shift in perspective often associated with the mid-life crisis. Such events are often regarded as fundamentally comic, even trivial, in nature. Yet what is Dante’s Divine Comedy if not such a crisis, writ mythopoetic?

“In the middle of the journey of our life, I came to myself, in a dark wood, where the direct way was lost…” — we’ve all been there, lately.

One good example, and of very readable length, is Alan Bennett’s The Clothes They Stood Up In. A late middle-aged couple return home from Cosi Fan Tuti one evening to find that their house has been burgled — but of everything. Beds, carpets, light fittings, the lot. Hence the title.

On an unexpected change of domestic circumstances…

I won’t spoil the story — it’s on Kindle, and less than £2 — but it takes several unexpected turns before the final curtain. It’s tackled as light, bittersweet comedy, of course, and deftly done. It has many of Bennett’s familiar tropes, and mild failings. It’s full of slightly twee vernacular and his sympathies fall a little predictably — though he acknowledges this at one point with an unexpectedly graceful meta-injunction on his characterisation of the husband.

But it is the effect the burglary has on the wife that has stayed with me. In particular, her tangible disappointment when their former life is restored, after all, and things return to “normal”.

This, as much as anything, is something we need to brace for, I suspect, when Lockdown lifts. And this gentle, very English book is a hint at some worthwhile preparatory meditations, tempered by some affectionate reflections on the likelihood of their making a damned bit of difference when it comes.

A Temporary Matter, by Jhumpa Lahiri

Recommended by Freya Sanders

If you could spend a year in solitude, where would you choose? “A house full of books” would have once been my answer. But now the hypothetical has happened, I’m quite unenthusiastic about reading. It only makes me feel more distant from social life.

If you feel compelled to read, though, read Jhumpa Lahiri. She’s an expert on the ways in which we can feel distant from one another.

In one of her short stories, A Temporary Matter — available in The New Yorker archives — a young-ish married couple receives a letter informing them that “for five days their electricity would be cut off for one hour, beginning at 8 P.M”. The inconvenience jolts the household out of its routine. For months, the husband has eaten dinner in his study, pretending to work; the wife has eaten hers in front of the TV. “With no lights, they would have to eat together.”

You sense that until now the lives of these two characters have crossed only in conversations about the washing up, complaints about coats not hung up properly. But now, thrown together for an hour, the couple start to talk. The wife suggests they each share one thing about themselves that the other doesn’t know. They do this, each night. Until, eventually, they address the elephant in the room.

The irony of social distancing is that a lot of people are suddenly spending a lot of time with loved ones who have been, for whatever reason, distant. Lockdown may, as some suggest, end in a cascade of divorces — but will be the confinement be the cause, or the catalyst? People, it seems, are perfectly able to trudge along together miserable peace, until something like the virus — or a persistent power-cut — makes such an existence impossible. But then what…

‘A Temporary Matter’ is the first in a Pulitzer Prize-winning book of short stories that is called, aptly, Interpreter of Maladies. Each narrative addresses one of life, and lockdown’s, big puzzles: how to communicate with those we’re stuck with, in sickness or in health.

Death in Venice, by Thomas Mann

Recommended by John Lewis-Stempel

In which wearied writer Gustave von Aschenbach, after encountering a tramp one revelatory Munich afternoon, suffers a ‘contagion’ of desire to travel to the Venetian lagoon, where he falls lovesick for the boy Tadzio, wearer of sailor suit and bearer of golden curls.

Cosmetically de-ageing (he believes, tragically) with hair-dye and rouge, von Aschenbach then falls physically sick with Asiatic cholera. “And before nightfall a shocked and respectful world received the news of his decease.”

This is the novella for this time of pestilence, but also the novella for all modern time. Because our entire lives are diseased. Famed for its languid evocation of The Floating City (note that Tadzio is a homophone of adagio), Death in Venice is more truly the existentialist fiction that prefigures Sartre.

There are no escapes, even in forbidden love, even in aesthetics. Mooning after Tadzio causes Aschenbach’s death since he fails to flee Venice in time. As for the ‘improbable’ beauty of the city, Mann turns over every exalted stone of Ruskin’s to show Venice’s decay: the mephitic canals, the petty thieves, the “hateful sultriness in the narrow streets.” Et in La Serenissima ego.

Significantly, Aschenbach, solitary and solipsistic, chooses not to go to his house in rural Germany for recuperation. The German countryside was filling with the Lederhosen hearties of the Vandervogel movement who pre-figured Nazism. (There really are no ways out from the dilemma of being.) Some authors have their fingers on the pulse. Mann had a lancet, carved the human body gob to groin, and placed his hand on its soul.

You’ve got to laugh. Truly. A novel interpretation of Mann’s novella would suggest endemic subdermal black humour. He is wickedly funny about the self-pities and the pretensions of The Writer in maturity. Aschenbach “banished from his style every common word.” He could not indite “smelly”, he had to scribe “mephitic”. It was von Aschenbach’s first malady, his lucubration.

What’s Expected of Us, by Ted Chiang

Recommended by Sam Leith

I’m here to recommend a very short story indeed: the science fiction writer Ted Chiang’s ‘What’s Expected of Us‘. It’ll take you maybe three minutes to read, if that. But like a sip of a good wine, the taste lingers. Chiang’s story is a tiny squib on perhaps the biggest subject of all: free will. It’s a subject that seems particularly relevant at this time of global unfreedom, while we contemplate what we don’t know and what we’d rather not know.

The McGuffin for this story is a device called a Predictor: “Its only features are a button and a big green LED. The light flashes if you press the button. Specifically, the light flashes one second before you press the button.” The reader, the narrator says, has probably seen one — millions have been sold by the time you’re reading this. On the face of it they’re like a gimmicky executive toy. They work by sending a signal a second back in time. Everyone tries to find ways to “fool” them — but they can’t be fooled.

The story concerns the effect that these things have on people. Basically, they prove that free will is an illusion. As that knowledge sinks in, a global pandemic of why-bother sets in. People just… give up. They stop talking, stop doing anything. The narrator, it becomes clear, is issuing a dire warning — but why, and how, and from where? Aha: even for a short short story, no spoilers.

You can find this story online for free here. With a bit of luck, that taster will lead you to buy Chiang’s collection Exhalation — in which every story, though they aren’t all as short as this one, develops some giant idea. They do, to my mind, just what the best speculative fiction ought to. The best of them open up entirely other worlds and imagine what it would be like to live in them — or posit huge ideas in logic or ethics and work out just what it would mean to live with their consequences.

This is Pleasure, by Mary Gaitskill

Recommended by Rowan Pelling

The single aspect of normal working life I miss most is gossip. Without humans interacting in the same physical spaces over extended periods of time, there’s no flirting, no power games, no rebellions and no febrile soap opera. Or, at least, not the sort you can witness, or have retold to you in exquisite detail by a gimlet-eyed observer.

The crimes and recriminations of #MeToo suddenly seem to belong to another era. But Mary Gaitskill’s brilliant (and I do mean pitch-perfect on every level) novella This Is Pleasure plunges you right back in.

Quin is a foppish, married publisher who conducts numerous tendresses (why do the French have words we so painfully lack?), but not love affairs, with young women who he tells himself he wants to pique and spur on to greater things. His intimacies involve many, small provocations and a few undeniable, graver trespasses. Quin is outrageous and quite possibly dangerous, but also entertaining and compelling. He’s exactly the sort of person many of us do allow greater leeway than we should, for fear of boredom.

This new novella will make you miss office politics.

Quin’s close friend Margot also edits books and has graduated from being one of his prodigies/playthings/experiments — it’s hard to tell which — to being a family guest and confidante. She has experienced his inappropriate behaviour first-hand, but also his unforced generosity, professional support and joie de vivre. Margot has chided him, “You delectate pain,” but never intervened — something that will haunt her after Quin is denounced, fired and becomes a social pariah.

The novella is conducted in short chapters that alternate Quin’s and Margot’s points of view. The sense of two eras, before and after #MeToo, is deftly interwoven. This is a work that’s purely concerned with the grey areas. Quin is by no means a rapist and Margot is not by nature an appeaser. Nevertheless, they have been complicit. The degree to which one or both are guilty can only be decided by the reader and everyone will put down this book with a slightly different verdict.

The strange thing is that you may also find yourself nostalgic for the office world of power-games and dodgy gallantries. If there’s one thing worse than your colleague’s “micro-aggression”, it’s being bored out of your skull.

Houston, Houston, Do You Read, by James Tiptree Jnr.

Recommended by Matthew Sweet

My friend Una McCormack is an accomplished science fiction writer. Last year she introduced me to another. James Tiptree Jnr.

Who’s he? I asked. It’s complicated, she said.

She was right. In the 1970s Tiptree was celebrated as the Ernest Hemingway of sci-fi. However, neither readers nor peers nor publishers ever clapped eyes on him — which meant they had no idea he was really Alice Bradley Sheldon, a former CIA officer who chose her nom-de-plume while reading the labels in the jam section of her local supermarket.

Tiptree’s stories are about change — how to manage it when it happens, what to do about it when it doesn’t. They are about women — sometimes as individuals, sometimes as a collective — negotiating a solution to the problems of male power.

The short story collection Her Smoke Rose Up Forever gathers a set of bright hard gems that might reflect some light on our own historical moment. The Women Men Don’t See (1973) maroons its narrator in a mangrove swamp with a mother and daughter who, much to his bafflement, decline to behave like damsels in distress. The Screwfly Solution (1977) is set in a world overcome by a pandemic of male sexual violence: men have literally declared war on women, in an act of organised revenge upon Eve.

Don’t judge an author by her cover.

But perhaps Houston, Houston, Do You Read (1976) is her masterpiece. It’s about three male American astronauts who encounter unexpected company on a circumsolar mission — another spaceship, staffed by women who speak in Australian slang. At first the men hypothesise that the new ship has tumbled from the future through a black hole. However, it soon becomes clear that the traffic has moved in the opposite direction. The Earth to which they are returning is one in which plague has wiped out the male population, leaving women to figure out new ways of maintaining human life.

What should the new world look like, Tiptree asks. Whose skills will be most valued? And who will find themselves irrelevant? Questions we might ask as we shelter at home, while nurses and cleaners and shelf-stackers take up their positions on the front line.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeYes, I had noticed that my attention span has been reduced, not least because I need the constant dopamine of another podcast from Jimmy Dore or Tim Pool or Steve Turley or The Hill etc. As such my reading right now is a very lightweight collection of Jim Walsh’s journalism on Minneapolis and its music scene, and the somewhat more heavyweight collected prose of Zbigniew Herbert. Good job I finally got around to, and finished, Dostoevsky’s ‘Devils’ just before this whole thing really kicked off.

Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, by Jorge Luis Borges

Recommended by John Gray

Thanks John, looks like an interesting book of short stories, but I think i’ll give it a miss…

Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius Paperback ““ 15 Oct. 1982

by Jorge Luis Borges (Author)

5.0 out of 5 stars 2 ratings

See all formats and editions

Paperback

from £209.38

4 Used from £209.38

I recommend England and other short stories by Graeme Swift, a lot cheaper too!

Every time I read the expression ‘Muslim feminist’ I’m amazed that it is accepted in mainstream articles and news reports.

Muslim ideology is based on the Quran, anyone who reads that will find that the expression ‘Muslim feminist’ is a contraction in terms, an oxymoron. It’s as if the term ‘ ‘feminist’ has lost all meaning.

What’s happening? It’s like the term ‘woman’ is now no longer a sufficient descriptor; it now needs to be qualified: cis-woman or trans-woman. Or, for cis-women, we can happily now also use ‘people with a cervix’. On the road to lucidity and sanity we are not.

Perhaps One rational position about the Muslim movement, I’m quite sure they still recognise ‘woman’ as a word that is sufficient on its own. How fantastically ironic!