The internet needs better policing. Credit: Peter Macdiarmid / Getty

As our exit from Europe continues to dominate daily politics, other, vitally important areas are being neglected. So what should our politicians’ priorities be once we are beyond Brexit? We asked various contributors to draw up a pledge card for a post-Brexit manifesto.

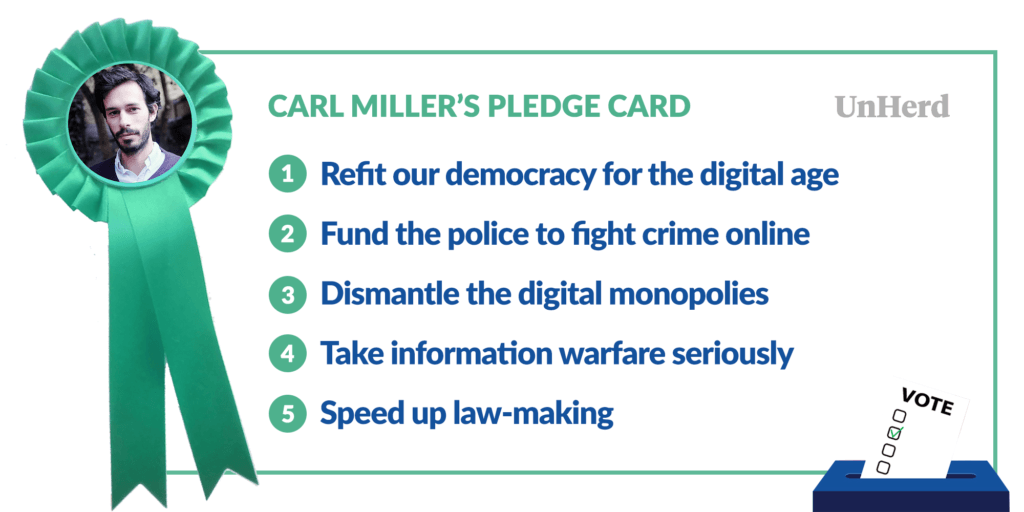

1. Refit our democracy for the digital age

One of the few things that unites the majority of the electorate is the idea that democracy isn’t working. People on both sides of the Brexit fence feel betrayed and ignored, and their overwhelming sense is that democracy did not do what it was supposed to. Voters, some say, didn’t know the facts. Parliament, say others, haven’t listened to the people. Ultimately, the whole thing exposed differences that government has been unable to reconcile.

We need a new wave of politicians who are determined to change democracy. They need to look across the globe of how to weave technology and democracy together to give people a clearer idea of the facts, as well as new opportunities with which to participate in decisions, and to bring to the fore consensus, rather than division.

New online political spaces with completely different kinds of plumbing to Twitter or Facebook are possible. As people propose solutions and respond to them, the ones that are seen are the ones not only your group, but the majorities of other groups can find agreement in as well. Digital spaces that can surface consensus are ones that, slowly but surely, politicians can begin weaving into decisions.

2. Fund the police to fight crime online

Behind the very visible problems with our political processes are those kept well hidden. None is more serious or neglected than cybercrime.

The way crime happens has changed enormously since the turn of the century. Half of crime now happens through the internet, at least in part through romance scams, online fraud, ransomeware or prodigious amounts of intellectual property theft.

Crime in digital form poses a particular and extremely difficult challenge to our police force. In investigation after investigation, the police find the victims of crime in one country, the evidence in another, and the perpetrators in a third, fourth and fifth. Crime on the internet travels like the wind across borders. Much less able to cross those borders are the law enforcement officers trying to stop it.

The moment crime began to migrate online, everyone thought it was falling. In fact, it was transferring to online venues most people didn’t know existed. That has produced a dangerous and lingering political fiction: that it’s possible to cut crime and police budgets at the same time. We have 21,000 fewer officers than in 2010, and budgets are now down by a fifth.

Our government must commit to a complete overhaul of the police system and stump up enough money to fund it. Crime has changed. The police must do the same.

3. Dismantle the digital monopolies

A tiny number of software giants have eaten entire sectors of the economy. Today’s dominant media companies – Spotify and iTunes – are software companies, and so are the world’s largest advertising (Google, Facebook), telecoms (Skype), recruiting (LinkedIn), taxi (Uber) and payments (PayPal) firms.

They have been swept to the top by a new commercial logic, based on network effects and enormous amounts of data. The largest networks create the most data, which makes those networks smarter and better, causing more people to use them, which produces even more data, and on and on it goes. Normal capitalism creates a field of competitors. This logic has created a tiny number of dominant winners that no-one can compete with.

Put bluntly, capitalism is broken. Dismantling the monopolies of the digital age has to be central to the agenda of any government that cares about free markets and opening up competition, consumer rights, and challenging the system’s vast concentration of power and control.

4. Take information warfare seriously

No-one can claim not to have been dimly aware that something was happening in the run up to the EU referendum. During the election campaign of Donald Trump, the alarm bells grew a little louder. A strange new kind of ‘information warfare’ has broken out as the Internet and social media are weaponised to interfere in elections, debates and the general politics of liberal democracies. Given that Brexit will be swiftly followed by a general election, we need to take the threat seriously.

Much like cybercrime or the new species of monopoly, the challenge information warfare poses undercuts the way that we protect ourselves. Again, the solution begins with political will. Our security apparatus needs to be reformed to monitor campaigns and detect these threats. The security treaties we’ve signed up to, especially NATO, need to be changed to recognise that there are some forms of attack that really can happen through Tweets, memes and viral posts. Authorities need to be encouraged by politicians to name, sanction and respond to at least the worst cases of information warfare, as and when they happen.

5. Speed up law-making

My last pledge is the most important but also the most difficult to deliver. The Government must move more quickly. Pledges will mean nothing if they remain pledges. They have to become law. It can take years to pass a parliamentary bill into law, and for good reason. They need to be debated and scrutinised line by line. After amendments are passed, those need to be scrutinised too.

Yet, the looming threats facing politics over the coming decade are now changing as quickly as the technologies that are woven through them. Politics must contend with, and of course govern, a reality that is accelerating all around them.

This issue will be at the heart of many of the most serious problems in future politics. It’ll cover everything from your rights in the workplace to your experience as a consumer, the health of a free press to the health of the environment.

How do you make the law move faster without sacrificing oversight? I don’t know the answer, as I don’t think anyone does yet. But anyone who takes this question seriously – who recognises that this is the existential question not just of political ideology but the relevance of politics itself – well, they have my vote.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe