Credit: View Pictures/UIG via Getty Images

As our exit from Europe continues to dominate daily politics, other, vitally important areas are being neglected. So what should our politicians’ priorities be once we are beyond Brexit? We asked various contributors to draw up a pledge card for a post-Brexit manifesto.

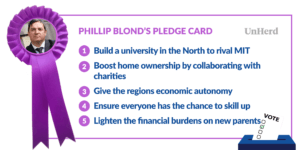

1. Build a university in the North to rival MIT

Most of the debate surrounding the UK’s North/South divide has focused on things such as hard infrastructure and transport deficits. But since the industrial revolution, what the North has really lacked is software, not hardware – there aren’t enough people with MAs and PhDs working in key areas such as applied technology.

Evidence suggests that the presence of tertiary degree holders and applied tech universities (such as MIT) is decisive in reducing wider economic imbalances. So let’s think big and put a brand new, massively-endowed applied tech university in the middle of the North.

Why a new one? Because most northern universities are not focused on applied technology, are not high enough in the world rankings, and are too path-dependent to shift at the scale and pace required. The model should echo Imperial College London’s: the university was founded in 1907 (around 800 years after Oxford) because the UK was afraid its scientific research would fall behind Germany’s. Thanks to support from the government (and the royal family, of course) Imperial became one of the world’s elite universities.

Let’s show similar ambition for the North.

2. Boost home ownership by collaborating with charities

A new ‘guaranteed buyer model’ for the UK housing market has long been promoted by my think tank, ResPublica. We suggest that not-for-profits and the private or public sector should join forces to buy homes at scale, then rent them out long-term.

This would create an investment surplus, which could be used for the public good. For example, the prices of a third of the houses could be frozen, until their tenants can afford to buy them. The proceeds from these purchases could then be reinvested, and the model repeated over and again. With the remaining houses, the aim would be for not-for-profits to buy out the other parties – meaning that, if publicly funded, the model would only temporarily contribute to public debt, without adding to the deficit.

Implementing this model could stimulate the construction of tens of thousands of additional homes each year, since the market only builds what it can immediately sell. Thus we’d address the true problem that limits housing supply: the limited speed and scale of construction.

This guaranteed buyer scheme would offer security to those whom the market has doomed to be nothing but renters for the rest of their lives.

3. Give the regions economic autonomy

If we are serious about tacking regional inequality, then we have to do more than simply sigh and say it’s an inevitable consequence of London’s success. As Professor Phillip McCann put it after an exhaustive survey, “the UK is one of the most interregionally unequal countries in the industrialised world”. This problem is serious: it’s time for macro-economic solutions.

As the Northern Powerhouse Partnership recently argued, devolving road taxes – such that fuel tax and exercise duty could be replaced with road price charging – could raise £8 billion for the North. Imagine what bolder measures might achieve.

We’ve already conceded and devolved powers to the home nations: Northern Ireland can now reduce its Corporate Tax rate; Scotland can vary its income tax rate. Let’s combine both these powers and offer them to the English regions (some of which, after all, are more populous than the other nations in the UK). Let them compete for the businesses they need – and, to make the regions even more attractive, let the costs of any relocation be 100% tax deductible. That might finally allow us to create the fiscal platform we need to tackle our extreme regional inequalities.

4. Ensure everyone has the chance to skill up

In the UK, we over-invest at scale in the 50% of young people who go to university, and effectively abandon the rest as they take the poorly-funded vocational path. Then, we as a country never offer anybody any training ever again – unless you get so far from the labour market that you’re classed as insecure or vulnerable. This is a woeful approach.

Though the returns on education are falling, skills still boost wages by 10% – and productivity by far more. Yet post-university – and despite the coming epochal, AI-driven shift in the labour market – we have no national programme to address the vast, diverse, increasing need for skill and training opportunities.

Britain’s overall skills base lags behind many comparable countries, as a forthcoming ResPublica paper points out, coming 24th out of 34 OECD countries for intermediary skills. Overall, the UK’s profile suggests the nation struggles “to meet the requirements of the technologically advanced sectors”.

We need a national, modular, employer-specific training programme – one which, based on innovation projections, promotes future skills. And it should be accessible to all: mothers returning from childcare, workers wishing to retrain, and young people who never went to university but want to secure jobs that require specific skills.

5. Lighten the financial burdens on new parents

The birth and care of young children puts parents under enormous pressure. Some manage by stopping work – giving up income to become full-time caregivers. Others outsource care to a nursery, which is often astronomically expensive – for themselves or, if the child is over the age of three, for the state.

But at the moment, single-earner households in the UK are the most heavily taxed in the OECD. Rates for such families are 70% higher than for comparable families in France, and 15 times higher than those in Germany. In the UK, just when young families are under the most pressure, we press parents between a rock and a hard place.

Better to offer a genuine choice to parents – following the example of Germany, where parents can choose to remain at home during their child’s earliest years. Perhaps one of the simplest and swiftest ways to support single-earner families is to allow the full transfer of the stay-at-home spouse’s tax-free allowance to the one who is working, during the first three years of a newborn’s life.

Unlike the pitifully small Marriage Tax Allowance, such measures would genuinely make a difference.

Click here to compare Phillip Blond’s pledge card with the others in our Beyond Brexit series.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe