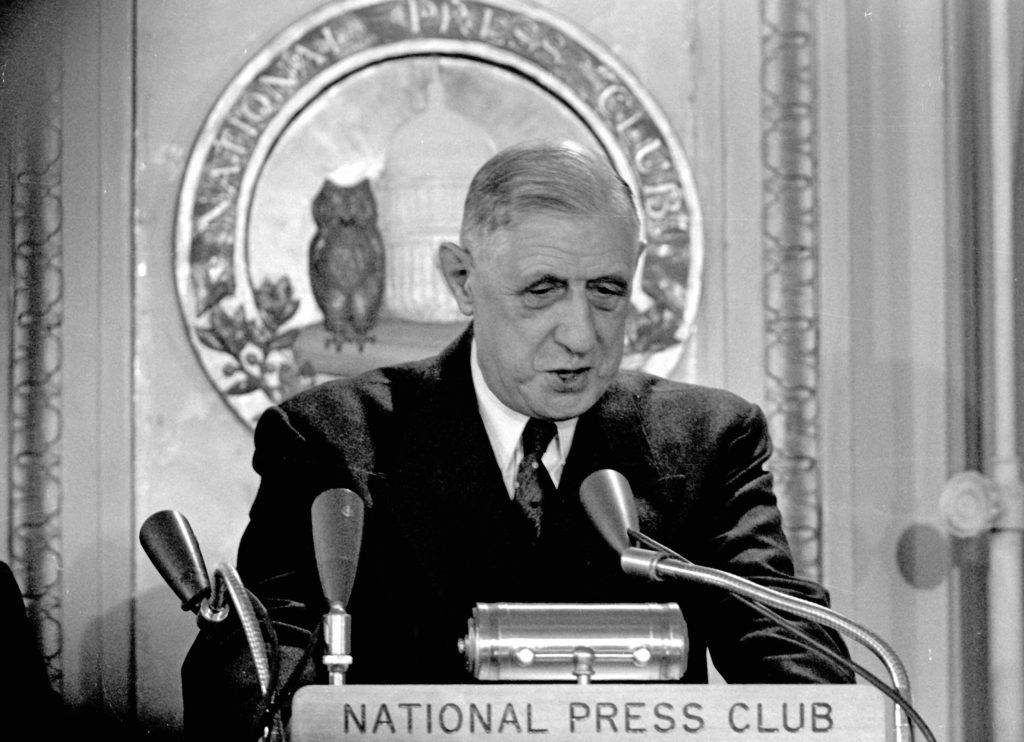

A statue of French president Charles de Gaulle. Credit: sigurcamp/Getty Images

Ask any conservative French politician to define his or her vision for society, and it is an absolute certainty that they will mention Charles de Gaulle. The name of the country’s Second World War leader, and most famous modern president, is shorthand for Gallic might and morality – the embodiment of all that makes traditional citizens proud of themselves in the land that also produced Joan of Arc.

Such reverence has not only motivated those seeking public office, but united the population through extremely turbulent times. The precise meaning of Gaullism has been debated constantly, but adherents generally describe it as a version of nationalism expressed through centralised government – one that places trust in a dynamic figurehead who knows exactly where France has been, and where it is going. It views Leftist politics as inherently divisive, replacing it with Right-wing consensus. The result, Gaullists argue, is effective rule.

Just as Britain undoubtedly benefited from a post-war consensus, so Gaullism helped produce les Trente Glorieuses – the three decades of impressive economic growth that started in 1945. The Republic took on challenges with a near-Napoleonic vigour, asserting herself on the world stage as a self-styled rival to America and the Soviet Union, while also claiming joint leadership of Europe alongside Germany. Even those who might be considered diametrically opposed to everything De Gaulle stood for – including Socialists and members of the far-right Front National – adopted the Gaullism tag when it suited them.

In fact they still do, and this is one of the reasons why contemporary usage of the term must be revised or – even better – slain like a once powerful but now woefully anachronistic dragon. Gaullism has outlived its rational historical usefulness, and those trying to manipulate the ideology for electoral gain need to think up something far more original and relevant to the modern era.

A key date in the long sweep of history relating to De Gaulle is 1970 – the year Le Général breathed his last at Colombey-les-Deux-Églises, his adopted village, east of Paris. Announcing this massive shock to the national psyche on television a few hours later, President Georges Pompidou simply said: “General de Gaulle is dead. France is a widow.”

It was perfectly acceptable that those who immediately carried on where De Gaulle left off, including Monsieur Pompidou himself, called themselves Gaullists. Theirs was an exercise in restrained pragmatism focused on a very particular idea of France. De Gaulle’s base was made up of white, Roman Catholic conservatives who had a quasi-mystical faith in their rural nation – or La France profonde as it was often referred to.

What was ignored, however, was a changing France – one that encompassed millions of new citizens linked to the decolonisation process that De Gaulle had presided over. Globalisation – including the spread of Anglo-Saxon culture – was among numerous other major developments that Gaullism struggled with.

Far more than that, Gaullism has never found another Charles de Gaulle, or anyone approaching his stature. On the contrary, the low depths to which it has sunk is illustrated by the appalling record of recent Gaullist presidents.

Jacques Chirac (who served two terms between 1995 and 2007) is now a convicted criminal. He received a two-year suspended prison sentence for financial corruption linked to his time as Paris mayor. His successor Nicolas Sarkozy (one term 2007–2012) is an indicted criminal suspect facing far more serious charges, including claims that he accepted millions from the late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi and, inter alia, bribed a judged.

François Fillon, once the runaway favourite to become President, also risks trial and prison for stealing money from the state along with his British-born wife, Penelope Fillon. The couple is accused of setting up a fake job scam that defied their image as devout Catholic parents dedicated to the public good.

It was with breathtaking arrogance – not to say a fair amount of hubris – that, in August 2016, Fillon attacked Sarkozy when the pair were competing to stand as presidential candidate for the Republicans, the current name for the Gaullists. Sarkozy was as usual under judicial scrutiny, leading Fillon to sneer: “It’s useless to speak of authority when we are not irreproachable ourselves. Who can imagine for a single moment General De Gaulle under criminal investigation?”

Fillon was charged a few months later, yet did not see this as a motive to end his candidacy to become the latest in a line of thoroughly disreputable Gaullist leaders. Such cynicism was accordingly punished by electoral defeat.

Thus lacking a charismatic chief and contemporary outlook, it’s hard to see how Gaullism and its antiquated dogmas can continue to thrive.

Emmanuel Macron, the former Socialist Minister who now runs France as an independent, is regularly portrayed as a Gaullist because of his high international profile and Jupitarian persona, but this has far more to do with lazy language than descriptive precision.

In a speech made in English to the U.S. Congress this week, Mr Macron went so far as to decry “the illusion of nationalism”, because it forced “the western world back in to the dark ages”. He added that “closing the door to the world will not stop the evolution of the world”. The underlying message was of renewal while working with trusted allies on a worldwide scale, not trying to revive an ailing Gaullist dragon that should have been buried years ago.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe