Credit: Justin Sullivan/Getty

Do you know the difference between a continuous payment authority (CPA) and a direct debit? No? Neither did anyone in the UnHerd offices (myself included). Nor, for that matter, do 79% of Britons (according to Citizens Advice). And yet millions of us have at least one CPA.

CPAs, also known as “recurring payments”, are different from direct debits because they are linked to your debit or credit card, not your bank account. They are often used for subscription services – like gyms, porn websites, beauty products, telecoms – and payday loans, and a CPA allows companies to take payments whenever they think they are “owed”. More than that, those companies don’t need to give notice of a change in payment date or amount. Which makes life nice and easy for the company but not so much for their customers who often find themselves trapped in subscriptions they can ill afford and never really understood in the first place (more on that opacity later).

Surely, though, you can just cancel the CPA by calling your bank? In theory, yes but like so many theories, the practice falls short.

Only 3% of websites offering a free trial are ‘problem free’

Half of consumers struggle to cancel or unsubscribe from a ‘free trial’

£490 is the poverty premium facing low income households

12 months since Philip Hammond promised “a green paper on protecting the interests of consumers”

A 2013 review by the UK’s financial watchdog, the Financial Conduct Authority, found that many banks were not cancelling CPAs when asked to by their customers, despite the law requiring them to.1 As a result, suitably chastised, the banks agreed to review all complaints about non-cancellations and repay those monies. And yet, two years on, that Citizens Advice analysis found that in 36% of cases where a consumer had requested a cancellation the bank did not comply.

But cancelling payments, while particularly urgent for families struggling to pay the bills, is just one issue. There’s a reason consumer groups talk about the “subscription trap”. We’re back to that opacity. The information imbalance between producers and consumers alone should be cause for concern – is there really a need for T&Cs to rival War and Peace? – and that’s before we even get to the shady practices, of which there are many. The “free” trials that sign you up to an ongoing paid subscription; the additional charges buried in small print and legalese; the hidden commissions; the automatic renewals.

A lengthy report from the European Commission, for example, found that of the 900 websites they screened across Member States, fewer than 3% were free of problematic practices associated with free trials.2 And almost half of consumers involved in a mystery shopping exercise had difficulties finding out how to cancel or unsubscribe from a service after a free trail. Consumers across Europe are being played. Last year the UK’s Consumer Protection Partnership named “subscription traps” as one of the key areas of “consumer detriment”.

Market purists will argue that unless the practices are fraudulent, government and regulators shouldn’t be concerned. Consumers are signing up to the free trials by choice, they’re entering their card details for the CPA subscriptions, it’s their fault if they don’t read the small print.

At best that’s a failure to recognise that yawning gap between theory and practice. It’s also a misunderstanding of Adam Smith, the doyen of free market capitalist theory. As I pointed out in my introduction to this series, the consumer, not the producer, should be king.

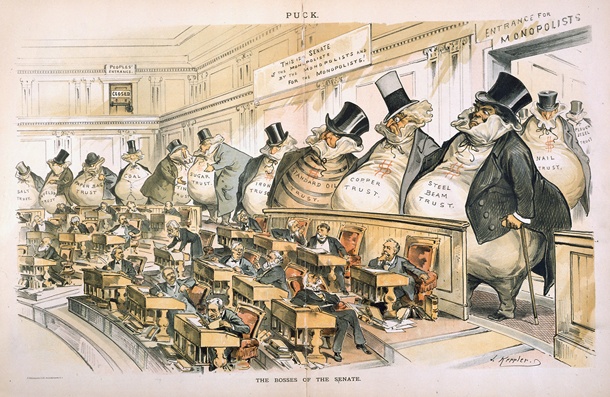

As each piece in our series highlights, the balance of power between producer and consumer has swung far too far in favour of the producer – or more specifically the big business producer. Misleading, tricking, or trapping consumers is not simply the by-product of a free market model, it’s evidence, as James Kirkup says, that the model is rigged in favour of producers. Just look at the recent miselling scandals, or the secretive online “dynamic pricing”, or the predatory practices, or the fact that regulators in various markets have had to step in and cap outrageous prices (payday loan interest rates, for example, have been a target in both the UK and America, though, off the back of heavy lobbying, the Trump administration look to be rolling back US consumer protections3). Look at the CPAs.

The UK energy sector in particular is a good example of bad practice. In our energy podcast Henry de Zoete talks about the “Freddy Krueger” model in which the “Big Six” energy companies entice consumers with loss-leading cheap deals before ratcheting up the costs a year later – what is known in the industry as “tease and squeeze”. A 2016 Competition and Markets Authority investigation found that energy customers were paying £1.4 billion a year more than they would be in a fully competitive market.4 The “poverty premium” experienced by low income households – on average £490 – is largely driven by sky-high energy tariffs. That is not Adam Smith’s capitalism.

Politicians, not just regulators, should care about rip off practices and oligopolisation – consumers are, after all, constituents. In Summer 2016, Democrat Senator Elizabeth Warren gave a speech attacking the monopolisation of US consumer markets.5 In it she said less competition means less consumer choice; less innovation and economic growth; and more lobbying, concentrated political power and regulatory capture. Our series this week shows that to be true.

Sadly, in America the Trump administration appears to be on the opposite path. In the UK, it is 12 months since the Chancellor promised “a green paper on protecting the interests of consumers”. “Left unchecked” Elizabeth Warren argued, “concentration will pervert our democracy into one more rigged game.” Time to rein in the big business oligopolies and put consumers back in the driving seat.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe