Credit: Richard Ellis via ZUMA Wire

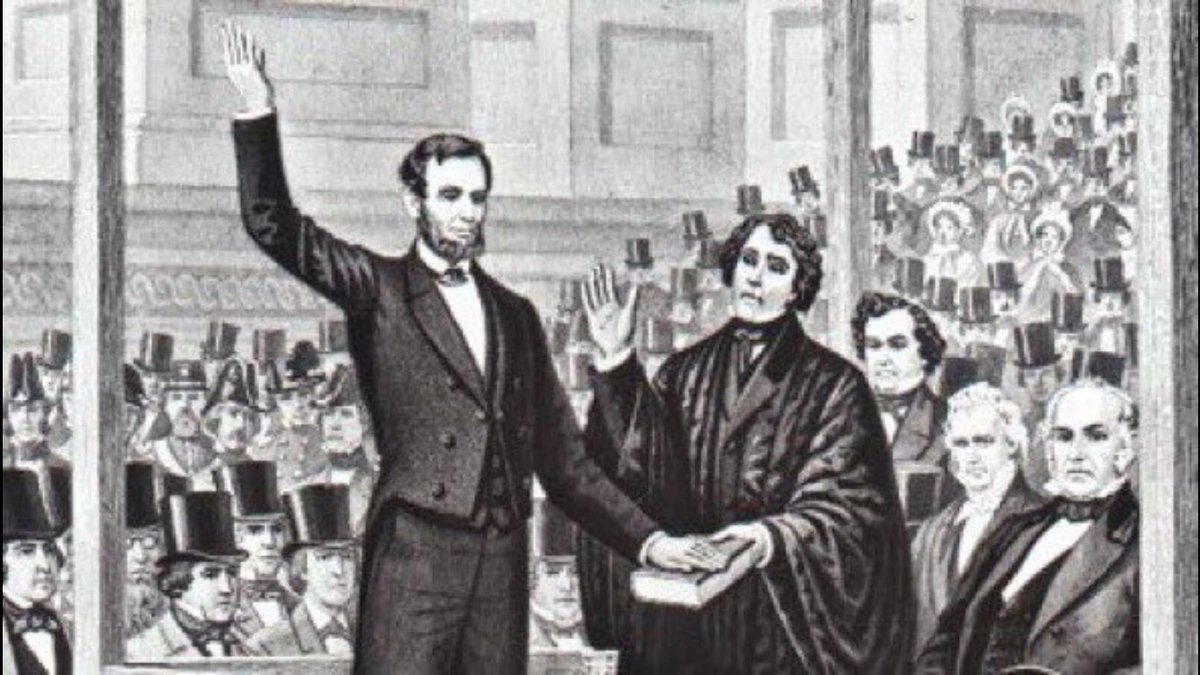

An attractive image accompanied UnHerd’s “Believers in Trump” series. In it, the First Lady’s elegantly gloved hands hold two bibles, one on top of the other; her husband has his left hand place atop these to take the oath of office during his inauguration in January 2017.

Most people know – because the media made a big deal of it – that the lower bible, in its protective box, was the one used at President Lincoln’s inauguration in 1861. The “Lincoln bible” is small – 6 inches by 4 – and bound in burgundy red velvet. It is an 1853 printing of the “King James Bible” (KJB), so-called because it was first published in 1611 during the reign of King James I of England (and VI of Scotland), and by his authority, “Appointed to be read in Churches”. Thus it was also known as the Authorized Version.

For three centuries, the KJB was the standard – indeed, almost the only – bible for English-speaking Protestants.

At the time of his own inauguration, Lincoln didn’t use his personal bible, but one kept for official use by William Carroll, clerk of the Supreme Court. When Lincoln arrived in Washington to be sworn, his personal belongings had not yet arrived. The bible remained with Carroll afterwards for a time, the Lincolns acquiring it only later. In 1928, the widow of Lincoln’s sole surviving son donated it to the Library of Congress, where it stayed until President Obama used it for the inauguration of both his terms (2009 and 2013).

Quite what President Trump intended by using the Lincoln bible is unclear, besides his obvious reverence for the man – Trump had, after all, been the presidential candidate of “the party of Lincoln”, as the GOP likes to be known (and from time to time needs reminding of). Some have speculated that choosing the bible that Obama had used was meant to be reminiscent of Lincoln’s words at his 1861 address: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection.”

It seems unlikely.

But what of the second, upper, bible? The media – even those two East Coast titans, The New York Times and The Washington Post – had nothing to say other than that it was a gift to the young Donald from his mother, Mary Anne MacLeod Trump, on the occasion of his graduation from church primary school in Queens, New York, in 1955. Trump, a Presbyterian, has said that he opens his bible and looks at it a lot. And, indeed, it is well worn.

The Trump bible is not, however, the same version as the Lincoln. It is the “Revised Standard Version”, which although much more recent that the KJB carries a good deal of “history”.

The Revised Standard Version (RSV) is an English translation published in the mid-20th century. While it traces its history to the English priest William Tyndale’s New Testament translation of 1525 – for which, inter alia, Tyndale would be judicially strangled and burned at the stake in 1536 – it is generally held to be a revision of the American Standard Version of 1901 (ASV), which was itself in some measure a revision of the KJB.

While, however, the ASV excelled in literal accuracy, this rendered it difficult to understand for the reader who was not well versed in the context of the original (Hebrew and Greek) texts. The RSV, on the other hand, is less accurate in its literal translation – or what is known technically as “formal equivalence” – but easier to read and understand, the translators being more concerned with conveying general, thought-for-thought meaning (“dynamic equivalence”). The translators had aimed for a good balance between the two, and one that maintained a degree of dignity in language (as in the KJB) while avoiding unnecessary opacity.

The RSV was published initially in two tranches: the New Testament in 1946, and the complete bible, with the Old Testament, in 1951 (on St Jerome’s Day, appropriately – Jerome having first translated the Bible into Latin). The first copy to come off the press was presented to President Harry S Truman.

It is this 1951 edition that President Trump used at his inauguration.

So what?

The Master Stroke of Satan?

The RSV – particularly the Old Testament – was not universally well received, especially by fundamentalist evangelicals. The criticism varied, was sometimes scholarly, and although perhaps seemingly arcane, touched nevertheless on core issues of doctrine. For example, Isaiah 7:14, in which the prophet promises King Ahaz of Judah that God will destroy his enemies, and that the truth of this will be shown in a miraculous sign. Both the King James Bible and the American Standard Version of 1901 render this passage in words well known to lovers of Handel’s Messiah: “Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel” – and thus the prophecy is linked to the coming of Jesus Christ through his birth to the Virgin Mary.

The RSV, however, disputing the original rendition in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures) of the Hebrew word almah as “virgin”, gives it instead as “young woman”.

This and several other disputed renderings, including some in the New Testament, troubled some even in the mainstream churches, but particularly in independent and fundamentalist congregations. The controversy added impetus to the so-called King-James-Only-Movement, which held that all recent versions were based on flawed linguistic scholarship and dubious texts (the RSV had made use of some of the early discoveries of the “Dead Sea Scrolls”). Indeed, Isaiah 7:14 became something of a litmus test in assessing new editions.

Some critics took to dramatic protests. Baptist Pastor Luther Hux, of Rocky Mount, North Carolina, delivered a two-hour tirade against the RSV, which he described as “the Master Stroke of Satan—one of the Devil’s Greatest Hoaxes”, and afterwards led his congregation out of the church, gave each worshipper a small American flag, and then set light to the pages containing Isaiah 7:14. There were other incendiarist pastors, although supporters of the RSV likened them to the burners of Tyndale.

For Trump to have decided to use the Revised Standard Version, therefore, is significant. It either suggests that this degree of literalism in the United States has abated, to the point that electorally it does not matter (Trump’s campaign continued, and continues, long after the election), or else he was unaware of the controversy.

It seems unlikely, however, that in his pursuit of the white evangelical vote he can been unaware of it, even if deciding that it is ignorable; he certainly didn’t try to disguise the fact that he was using the Revised Standard Version at the inauguration, for the words are clearly visible on the spine. So perhaps the lack of any apparent backlash indicates that it was a good judgement call. Yet why should he risk it?

Whatever the truth, the mere fact that President Trump’s choice of second bible has gone wholly unreported in a nation with such sophisticated media may be something to ponder on.1

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe