Credit: Schifres Lucas/ABACA/PA Images

One hundred years ago, in early 1918, President Woodrow Wilson launched his audacious ‘14-point programme’ – a bold, open-handed power play. The United States, having entered the First World War less than a year before, laid out a peace plan it was willing to enforce with hard power, upending relations between a previously dominant Europe and the upstart ‘New World’.

Wilson’s speech marked the start of ‘the American century’ – his country would lead a ‘liberal coalition’ of Western democracies, supported by smaller client states elsewhere. That was the moment, perhaps more than any other, when the US, newly-crowned as the largest economy on earth, laid claim to global hegemony.

China’s current rise to global hegemon has so far been rather different. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) already acknowledges that the People’s Republic has overtaken America as the largest economy on earth – at least on the basis of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), a measure that adjusts for differences in prices. But China, for now at least, seems unlikely, unwilling and unable to usurp the US by taking on a military leadership role, engaging in far-flung conflicts or acting as a global arbiter of peace.

The route Beijing is plotting towards worldwide influence and control is more gradual, based less on military prowess, more on economic and financial might. China’s fast growth – averaging more than 7% a year for more than four decades – is now widely acknowledged and understood. Those watching closely may also have noticed that Beijing, off the back of China’s awesome export machine, has amassed the world’s largest stock of foreign exchange reserves – its $3,300 billion haul exceeding that of the entire G7 combined.

Beyond the headlines, though, other developments, far less noticed but no less telling for that, illustrate the extent of China’s financial progress and the scope of its global ambition. And the most significant for a while will be next month’s launch, after a 25-year wait, of oil futures contracts, denominated in yuan, listed on the Shanghai stock exchange and available to global investors.

The launch of a new financial instrument, which sounds rather technical, won’t trouble many Western headline writers on 26 March – the date, just announced by the China Securities and Regulatory Commission, that these contracts will first trade – they’ll no doubt remain fixated on celebrity tittle-tattle, Brexit and Trump. But these new contracts represent a big step in China’s long-held ambition to establish the yuan as a major reserve currency, perhaps one day replacing the dollar as the denomination of choice for worldwide trading, settlement and, crucially, in which central banks hold their reserves.

The key to reserve currency status, history shows, is being a petrocurrency – the currency in which crude oil is priced and traded. China is working on that, too. As it strives to challenge the dollar’s dominance, Beijing boasts important allies – including oil export giants Russia and possibly even Saudi Arabia. And now, by denominating oil contracts in yuan, and allowing them to be traded globally, China will be taking another important step in promoting the use of its currency around the world.

The “exorbitant privilege” of reserve currency status

For much of the 19th and the first few decades of the 20th century, sterling was the world’s reserve currency. Some time during the 1930s, with America confirmed as the world’s commercial powerhouse, having eclipsed the British Empire several decades earlier, the dollar took over as the global currency of choice. That reserve currency status was then confirmed at the landmark 1944 summit in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, which set up the IMF, World Bank and other US-dominated institutions which formed the architecture of global financial governance that remains broadly in place today.

Since then, global commerce has been conducted largely in dollars and leading economies have held the greenback as their primary reserve currency, in their respective large companies, treasuries and central banks. The advantages this bestows on the US are enormous. Reserve currency status generates huge demand for dollars from governments and firms around the world. This has allowed successive US administrations to spend far more, year-in year-out, than is raised in tax and export revenue.

By the early 1970s, US economic dominance was so assured that even after President Nixon reneged on the dollar’s previously unshakeable convertibility into gold, amounting to a massive default, dollar demand kept growing. As such, for several generations now, America has not needed to worry unduly about balance of payments crises, as it can pay for imports in dollars printed by the Federal Reserve.

Washington can borrow and spend, then, pretty much at will, as long as the world keeps buying ever more US government bonds. The Fed, in other words, uniquely in the world, can ‘print hard currency’.

It is this “exorbitant privilege” – as French statesman Valéry Giscard d’Estaing once sourly observed – that has been the bedrock of America’s post-war hegemony. It is the status of the dollar, above all, that has allowed Washington to get its way, putting the financial squeeze on recalcitrant countries via the IMF while funding foreign wars. To understand politics and power it pays to follow the money. And for most of the past century, that money has been dollars.

A China-Russia tie-up is challenging US hegemony

That US hegemony is now being explicitly challenged – by China. In 2013, President Xi Jinping, laid out the ‘One Belt, One Road’ proposal, a modern equivalent of the old ‘Silk Road’, with Beijing creating a network of railways, roads, pipelines, and utility grids linking China, Central Asia, West Asia, and parts of South Asia. Comprising more than physical connections, OBOR is aiming to be the world’s largest platform for economic cooperation, trade and financial collaboration, as well as social and cultural exchange. This is no idle talk. The ratings agency Fitch estimates that no less than $900 billion of OBOR projects are currently underway.

In 2014, China then launched the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank, to directly challenge the World Bank. Based in Beijing, the AIIB channels a combination of state and private cash into infrastructure projects around the world – under the tutelage of China, not the US. America initially discouraged other large Western economies from joining the AIIB’s board, but Washington was defied, including by the UK.

China has, in addition, backed the creation of the New Development Bank (NDB), often referred to as ‘The Brics bank’. Established by Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, this Shanghai-based lender extends finance to both public and private projects globally, once again challenging the dominance of the US-led Bretton Woods institutions. Billions of dollars of NDB loans have already been extended for projects ranging from renewable energy, to rural drinking water, to information technology.

Aside from high-profile institution building, China is also asserting itself by building bonds of economic co-operation that, in turn, will boost the role of the yuan. It is in this regard that the new Shanghai-listed oil contracts are so crucial. And they are being launched in the context of an ever-strengthening bilateral relationship, of primary importance to both sides, between China and Russia.

Enemies for much of the Cold War, China and Russia have spent the last decade building serious commercial ties across their 2,700-mile border. Trade between them, just $12 billion back in 2007, soared to $85 billion last year. Both sides recognise the vast synergies between Russia, the world’s largest energy exporter and a bridge to continental Europe, and China, not only the world’s largest manufacturer but, since last year, the biggest oil importer too.

In 2009, Rosneft secured a $25 billion oil swap contract with China. The state-run Russian oil giant signed an additional $270 billion deal in 2013, agreeing to send an extra 300,000 barrels a day eastward for 25 years, doubling its crude supplies to China. Russia is now the largest exporter to the People’s Republic, selling around a fifth of its exports to China, which in 2017 averaged around 1 million barrels a day.

These crude exports have risen steadily since the 2010 opening of the Sino-Russian ESPO (East-Siberia-Pacific-Ocean) pipeline. A second ESPO pipeline then opened last month, doubling Russia’s export capacity to China. The geopolitical implications of this China-Russia tie-up are obvious, for those prepared to think them through – and not necessarily advantageous to the West.

Moscow, for one thing, with a major alternative buyer of its hydrocarbons, now has more price leverage when selling energy to Europe. But the broader importance of this emerging pan-Siberian link-up is that, by extending existing yuan-ruble swap arrangements, and settling massive energy trades in a currency other than the dollar, these two nations are directly challenging the predominance of the US currency.

Crude oil is currently priced in dollars, of course. The two main global price indices – for ‘Brent Crude’ and ‘West Texan Intermediate’ – are remnants of Anglo-Saxon global rules. But China’s voracious appetite for energy imports, and America’s increased focus on domestic production, mean the days of dollar-priced energy, and related dollar-dominance, are starting to look numbered.

That’s why Beijing has already struck numerous trade agreements with major commercial partners such as Brazil and India that bypass the dollar. If Beijing and Moscow – representing, respectively, the biggest demander and supplier of exported energy on earth – decided totally to drop dollar energy pricing, while encouraging others to do the same, America’s reserve currency status would start to unravel. That, in turn, would undermine the US Treasury market, seriously complicating Washington’s ability to rack up enormous annual budget deficits and finance its vast, and still fast-growing, $20 trillion of dollar-denominated debt.

The yuan may not become the reserve currency, but the era of the dollar is ending

Originally attracted by the dollar’s stability, the big emerging markets have become increasingly miffed in recent years by America’s deliberate currency debasement, as Washington has fired up the virtual printing press in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

Since the quantitative easing began, the US base money supply has ballooned from $800 billion in 2009 to well over $5,000 billion now. That’s bad news for foreign creditors like China, with vast dollar-denominated reserves and debt instruments, diluting the value of what they are owed.

These concerns over dollar depreciation, plus a desire to divert part of America’s “exorbitant privilege”, has seen China and Russia cut a number of non-dollar energy deals, which have the added advantage of avoiding US sanctions, or any other random controls imposed by the US banking system. Moscow and Beijing are now stepping up bi-lateral large-scale non-dollar settlement, in the form of currency swaps and specific deals. Much of the $27 billion Russia is using to finance its vast Yamal Arctic liquid natural gas project, for instance, is coming from Chinese lenders.

With these new crude contracts priced in local currency, Beijing is helping Russia – along with Iran, that other key power necessary for Chinese-led Eurasian integration – short-circuit US sanctions by trading energy in their own currencies, or in yuan.

Naysayers claim the dollar will stay supreme. On-going capital controls, which restrict movements of money in and out of China, will spook foreign investors, they say. So Shanghai’s oil contracts will remain an offbeat, exotic investment, rather than position the yuan as a petrocurrency.

Not so, the Chinese authorities shoot back. The yuan will soon be fully convertible into gold on both the Shanghai and Hong Kong exchanges, they claim. The key is that the dollar is being bypassed and, in this ‘Asian century’, the unique status of the US currency is a relic of a bygone era.

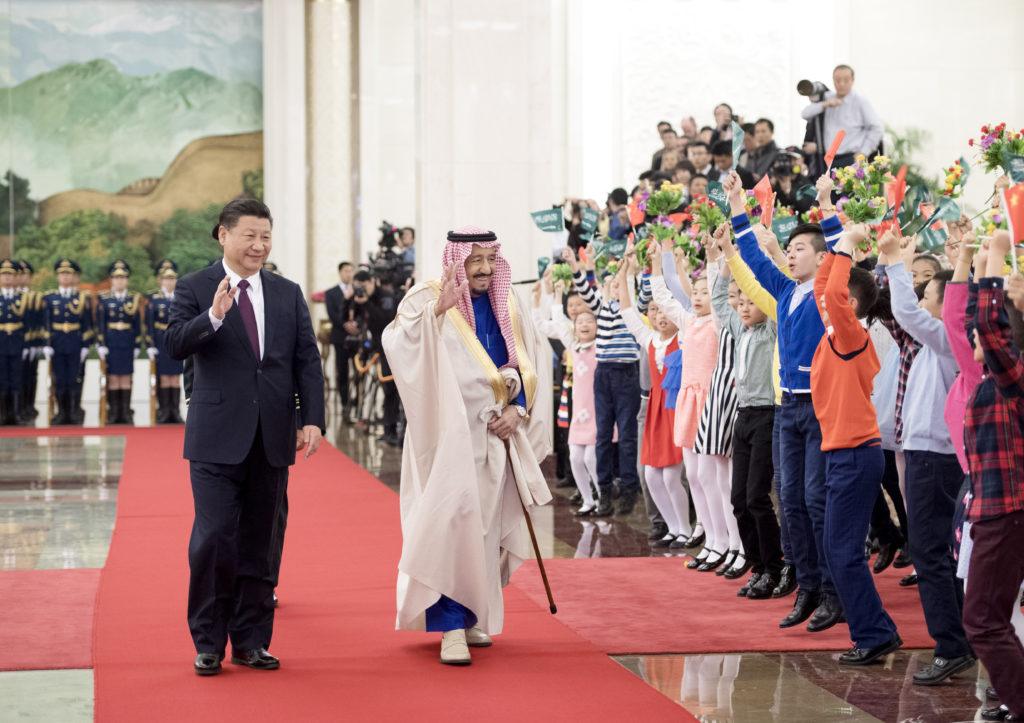

Beijing is staging a full-frontal attack, with other large powers in its corner. Along with Russia, China is also pressuring Saudi Arabia – the lynchpin of the OPEC exporters’ cartel – to price its oil exports in yuan. Beijing has already made an offer to “take a large strategic stake” in Saudi Aramco, the state-owned oil monolith, which an increasingly cash-strapped Riyadh is being forced partly to privatise. And with plenty of cash reserves at the ready, Beijing can extend further largesse to the Saudis, until it gets what it wants.

The dollar’s reserve status won’t end overnight. The US currency still accounts for around 60% of central bank reserves around the world, though that is down from 80% in the 1970s. But the yuan has made a start.

My guess is that, pretty soon, within a decade or so, a ‘reserve currency basket’ may emerge, with central banks storing wealth in some combination of dollars, yuan, rupee, reals and rubles, as well as precious metals. Perhaps some kind of synthetic mix of the world’s leading currencies will emerge, with emphasis placed, after years of QE, on assets backed by commodities and other tangibles, as well as crypto-currencies.

China’s new oil contracts, though, will expand ruble-yuan oil trading across the vast Eurasian landmass, and with broader non-dollar commodity trading beyond that, turn up the heat up on the West. It brings us closer to the dissolution of America’s unique reserve currency status, ushering in a new multipolar world order.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe