Liberal. No word in political philosophy seems to be so capable of such a variety of meanings. For some, it is fundamentally a philosophy of the Right — a philosophy of free markets, small states and individual freedom. For others it seems to have a leftward focus — open borders, minority rights, civil liberties. Little wonder that disputes involving the word liberalism are often ways for people to talk at cross purposes.

The distinguished political theorist Michael Walzer has offered a fascinating clarification in a recent essay in Dissent magazine ‘What it means to be Liberal’. Liberalism began life as an “ism”, that is, a substantial theory of political philosophy. But from sometime around the mid twentieth century, he argues, liberalism turned into an adjective, not a noun. It is now a qualifier to other more substantive ideas such as democracy, nationalism, Judaism, communitarianism, even monarchy.

To speak of liberalism as an adjective is to say that it qualifies and constrains the activity of the noun it describes. So, for example, liberal democracy represents the majority but is limited by things like minority rights, by freedom of the press to criticise, by the rule of law. Populism, on the other hand, is what happens when democracy seeks to throw off its liberal qualifiers in the name of majoritarianism.

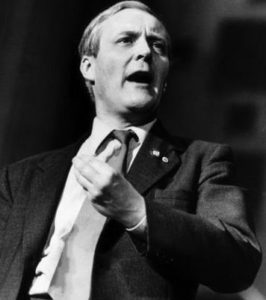

This is a helpful clarification. And explains what is at stake in the populist revolutions around the world. But it also raises the question as to how adjectival liberalism — liberalism as a qualifier of majoritarianism — establishes its own moral justification. If populist leaders gain their moral authority through the ballot box, how is the liberal qualification to that power to be justified? And how might it ever be legitimately challenged? This is rather important, because the liberal qualifiers to majoritarianism contain great power. So how, for instance, would the various forms of liberal qualifying power answer those famous five challenges as put by Tony Benn:

Where did you get it from?

In whose interests do you use it?

To whom are you accountable?

How do we get rid of you?

One of the important questions raised by populism is the extent to which qualifications to the will of the majority are a clever strategy for certain world-views or interests to assert themselves in a way that is beyond democratic scrutiny. For one of the charges made by populist democrats is that — to put it in Walzer’s terms — the adjectival form of liberalism is a disguised mechanism for protecting a series of largely middle class interests, shielding them from any form of democratic challenge. Or to put it another way: unable to achieve power from voters, certain interests have built it into the working software of democracy itself.

From Hungary to India to the United States, populism is becoming more and more effective at weaponizing the ballot box against its limiting liberal qualifiers. And unless these qualifiers — secularism, human rights, judge-make law, for instance — can do a better job at answering Benn’s five challenges, we shouldn’t be surprised if populism continues its worrying progress.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeI do consider my self as a liberal, as in everybody in a country should have as much freedom as possible and not to be constrained by large Government. I also believe in democracy and in accepting the democratic vote.

So I find that your statement that “populism continues its worrying progress”

as rather alarming.

Do you only believe in democracy if your side wins?

‘Or to put it another way: unable to achieve power from voters, certain interests have built it into the working software of democracy itself.’

Very well put, Giles. The liberals (most of whom have never worked at anything productive or useful) have abandoned the working/lower classes over recent decades. The result, in many places, is a populism that seems to me no worse than the liberalism that brought us Iraq and Afghastlystan, rule by and for the banks,the mass movement of people who were often forced to move wherever capital dictated, and many other awful things.

As for Tony Benn, had he come to power the gulags would undoubtedly have followed, probably sooner rather than later.

I would agree and add that the ‘progressive liberals’ from Blair to Obama, taking in the Remain part of the Tory party (Cameron) that held power for so long, also tried, very successfully, to eliminate the Right through the education system. It has moulded a huge part of the educated middle class to accept it’s principles: minorities dictating the way society is run, vast population movement, control of capital by large multinational banks, vast public and private debt and many other aspects of our lives today that need to be challenged and alternatives worked toward.