(Photo by Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images)

It went largely unreported, but at a Vatican conference on nuclear disarmament earlier this month, Cardinal Peter Turkson, who leads the Holy See’s dicastery (department) for “The Promotion of Integral Human Development”, explained that Rome was “exploring the possibilities of speaking to [North Korea] directly.”

This should come as no surprise, given that the Vatican has played a significant part in enabling better relations between the US and Cuba. Indeed, given the high stakes and the Vatican’s extensive and experienced diplomatic service, it would be surprising if the Pope took no interest beyond the prayerful and admonitory. What it all amounts to is impossible to say. Secret diplomacy is the best diplomacy, and the Vatican knows how to do things in secrecy.

There is, of course, a role for public diplomacy (propaganda, one might say, but uncharitably, for the word has only negative connotations nowadays1. If, according to Churchill and others, Stalin really did once or twice ask the sneering question “The Pope! How many divisions does he have?”, he was forgetting the huge resources the Soviets had always put into propaganda. There’s no substitute for hard power, but only when hard power is the only thing that works.

Pope Francis certainly made his position known at the disarmament conference, which was attended by the UN High Representative for Disarmament Affairs (the Japanese, Izumi Nakamitsu), and Nato’s deputy secretary general (the American, Rose Gottemoeller). The Bishop of Rome declared:

“The existence of nuclear weapons creates a false sense of security that holds international relations hostage and stifles peaceful coexistence.”

Intuitively, you would expect a pope to be opposed to weapons of mass destruction, but the Holy See’s position has also been nuanced. During the Cold War, successive popes granted conditional moral acceptance to the system of nuclear deterrence in order to discourage either the US or the Soviet Union from launching a nuclear attack. In 1982, Pope John Paul II stated that the system of deterrence could be judged morally acceptable as “a step on the way toward a progressive disarmament.”

However, in the context of threats of first use of nuclear weapons, Pope Francis voiced his concern for “the catastrophic humanitarian and environmental effects of any employment of nuclear devices” and that “progress that is both effective and inclusive can achieve the utopia of a world free of deadly instruments of aggression, contrary to the criticism of those who consider idealistic any process of dismantling arsenals.”

Or as one delegate put it:

“The condition under which there was a limited acceptance… those conditions have evaporated.”

The Pope has expert, military backing

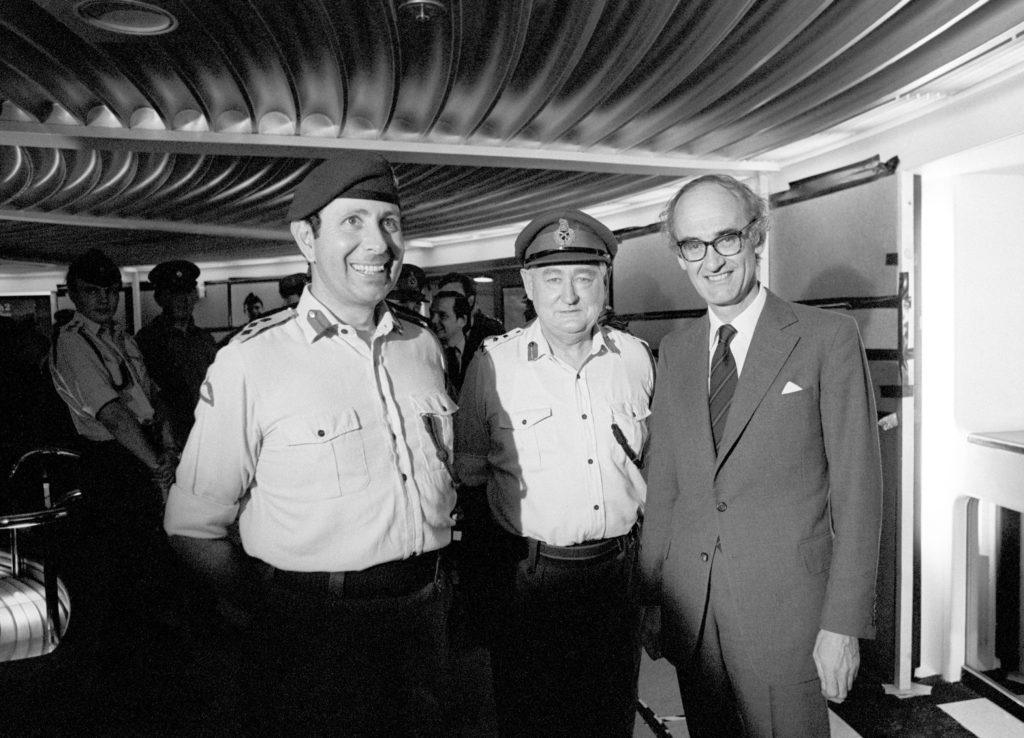

The Pope would have found (on the face of it) an unlikely supporter in one whose finger had been close to the button of Britain’s strategic nuclear deterrent at the height of the Cold War. Field Marshal Lord (Edwin) Bramall, Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS) 1982-1985, spoke strongly in favour of Britain’s nuclear deterrent posture during his first speech in the House of Lords, in 1987, after “retirement” (although a field marshal never technically retires). In his valedictory speech in the Lords in 2013, however, he argued against Trident renewal. Having first questioned the logic of maintaining such a strategic deterrent in 2007, he now believes the conditions in which that posture was necessary have evaporated.

Both the 2007 and 2013 speeches, and the position paper he wrote at the time of his parting shot, are included in The Bramall Papers: Reflections on War and Peace, recently published.

Both the 2007 and 2013 speeches, and the position paper he wrote at the time of his parting shot, are included in The Bramall Papers: Reflections on War and Peace, recently published.

His argument reflects not only his view of geo-strategic and military reality, but of moral authority of the type that Pope Francis evidently believes is both necessary and effective. He speaks of “a compelling but, I believe, fallacious argument that with Iran apparently close to acquiring a nuclear weapons capability, and North Korea flexing its nuclear muscle over the Sea of Japan, now is not the time to consider any change to Britain’s own nuclear stance.” Paradoxically, he believes that it is this very development that compels the opposite:

“It is because the threat of nuclear weapons falling into irresponsible hands is so real and worrying that we can no longer delay the review of our own nuclear deterrent system.”

Three questions that can longer be evaded

There are, Bramall argues, three closely-connected questions in such a review:

- First, from a military point of view, does Britain need a successor to Trident and would it be able to do the job intended for it? To this, he believes the answer is unquestionably “No”, arguing that such a system has not deterred, and would not deter, any threats or challenges to this country, nuclear or otherwise. Nor, in a now intensely globalised and interlocked world, could such a deterrent ever conceivably be used, not even after some seriously hostile incident (which it had presumably failed to deter). Britain’s national deterrent had never been truly independent anyway, “and if this country had not possessed one during the Cold War stand-off, it would certainly not be seeking such a capability now.” Moreover, he argues, conflict is moving inexorably in an entirely different direction, “so that the oft-quoted justification for such a status symbol—a seat at the ‘top table’—has worn thin.” He believes that prestige and influence are now derived from economic strength, wise counsel and peacekeeping rather than an ability to destroy en masse. Against this background, therefore, he is convinced that Britain does not need to maintain an ever-ready, invulnerable successor to Trident.

- The second question, which is where Pope Francis and Bramall so significantly converge, is: how can we make any positive contribution to dialogue over the reduction of nuclear weapons if the only example we set is to be a wholly negative one? “The claim that Britain must guarantee its security in all circumstances is a line of argument not lost, I imagine, on those who now wish to acquire such weapons for themselves.” (Nor on non-nuclear third parties who nevertheless wield power and influence; for example the EU).

- The third question is whether the British government – and successive British governments – is somehow politically-trapped. “Could it really defy popular feeling, so easily whipped up to claim that the government would be giving away Britain’s guarantee of security?” In political terms it could be dangerous for any party – witness Jeremy Corbyn – to propose such a step. It was and remains easier therefore to let a planned successor to Trident go ahead.

Bramall proposed, and still proposes, a way round this political impasse (emphasis added):

“We should give urgent consideration to adopting more practical, realistic and hopefully cheaper ways of warding off any likely threat to our nation, which at the same time would make Britain a leader in the non-proliferation dialogue.”

To begin with, he argues, we should recognise that there is no need for a nuclear-firing submarine to be at sea at all times in order to demonstrate an effective deterrent capability. Periodically one boat would have to be at sea for training purposes, and at others a submarine could put to sea at short notice if the threat level were perceived to have increased. Some worthwhile economies would arise from a system of reduced readiness. The existing Trident programme could be kept on for longer, which would help stave off the political threat:

“But more importantly, however, it would allow a breathing space in which to develop a more relevant, economical and useable system. Britain’s current and projected nuclear capability is geared towards immediate response. Stepping back from this state of preparedness would be a sound and progressive step.”

It would not be unilateral disarmament, and it would not be without precedent. After the break up of the Soviet Union, as a result of the “Options of Change” review, the UK gave up two of the three legs of the “nuclear triad” – battlefield nuclear weapons and sub-strategic (air-launched) missiles. There was no longer the means of nuclear escalation, therefore; only immediate resort to Trident. This was a highly significant step.

The money is running out

Since Bramall’s valedictory speech, various “gateway decisions” have been made to renew continuous, at-sea deterrence. This year alone, the unbudgeted cost increase in the programme is over £300 million. Yet as the chancellor, Philip Hammond, indicated in his budget speech (22 November), there will be no new money for defence. Trident replacement is now running at enormous opportunity cost to Britain’s armed forces, which, as I argued last week, are now in a more perilous condition than at any time since the 1930s. The secret review being carried out at present by the National Security Council is only considering defence costs in “tactical terms”; there is no strategic review as such. But the time has come to ask if we can truly afford a nuclear deterrent of the nature of Trident. The argument that the government would only spend the money on something else won’t wash. As a Nato member, we are committed to spending 2% of GDP on defence.

Four years ago, Field Marshal Bramall, now 93, who won the Military Cross in Normandy and was Margaret Thatcher’s chief of defence staff, wrote:

“Britain should not re-prepare for the last war, but instead present a better-balanced and more relevant defence programme. Moreover, by making a further and significant contribution to the general dialogue for multinational nuclear disarmament, it would enhance the value of our counsel in international affairs and as a key member of the Security Council.”

He remains of the same view today2.

If only we knew what the chiefs of staff truly thought.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe