Economists have been trying to put a monetary value on prayer by testing how willing people are to pay for it.

In a bid to reduce tender human experiences to pounds and pence — or dollars in this case — participants in the study were given $5 notes which they could either take away with them, or exchange for thoughts or prayers.

In a bid to reduce tender human experiences to pounds and pence — or dollars in this case — participants in the study were given $5 notes which they could either take away with them, or exchange for thoughts or prayers.

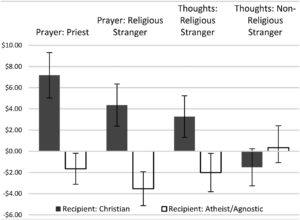

As you might expect, religious people were willing to pay to be prayed for (more if it’s a priest, not a stranger). Rather more surprising, was the fact that the non-religious were willing to part with cold hard cash in order not to be prayed for. They wanted shielding from prayer. Christians, meanwhile, weren’t particularly keen to receive ‘thoughts’ from a non-religious stranger.

It seems people (or at least Americans, which the study focused on) are as tribal and divided on this as on any other emotive issue.

The concept of ‘thoughts and prayers’ does carry particular cultural weight in the States, where it is so often parroted by politicians after mass shootings that it is taken as a cowardly alternative to action. But it was the strength of feeling about prayer in the non-religious that really struck me. If you don’t believe in the efficacy of prayer, why would it bother you that it’s happening?

It divides us in Britain too. Prospect magazine carried a piece on prayer this month, in which atheist Oliver Kamm became increasingly apoplectic at Catholic Dawn Foster’s suggestion that prayer might fuel positive action.

So I did some canvassing of my own. While some people said they didn’t mind praying, others admitted it made them deeply uncomfortable. Offers of prayer were received as implying moral superiority, or as attempts to convert. Religious friends felt slapped in the face by this, as if the most precious, loving thing they could offer had been stamped on.

We are so fragile and easily hurt, so quick to judge or feel judged. The wide difference in attitudes to prayer is part of the background atmosphere that makes talking about belief so difficult. My worry is that if we don’t talk about the deepest things, our existential hopes and fears, then these misunderstandings simply deepen. And I’m not sure economics can help us with that.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe