As inflation rages, strikes are taking place across Britain. The two phenomena are connected, and obviously so: understanding how is enormously important. Not only does it give us potential insight into the future trajectory of strikes and inflation, but it also allows us to get a sense of whether a wage-price spiral is taking hold in Britain.

A wage-price spiral is a situation where, after inflation takes hold, workers try to bid up their wages to keep pace with rising prices. But, faced with these rising wages, companies are then forced to increase their prices even more to offset the new, higher wage costs. This dance can go on interminably, meaning that inflation, which may have otherwise subsided, becomes entrenched in the system.

Wage-price spirals almost inevitably become a politicised affair, with those who consider themselves defenders of the working class denying their existence — or, if they are feeling even more radical, blaming capitalists for ‘price-gouging’. In recent days we have seen some credentialed people engage in denialism about this issue. Former permanent secretary to the Treasury Lord Macpherson, for example, declared that “public sector workers don’t create inflation”. Meanwhile, former deputy governor of the Bank of England Sir John Gieve questioned whether larger pay rises for public sector workers would significantly fuel inflation.

This is part of a broader trend, where Left-leaning economists deny the existence of a wage-price spiral altogether. Some claim that a spiral only exists when wage growth outpaces inflation; others claim that inflation must be accelerating for a spiral to be taking place.

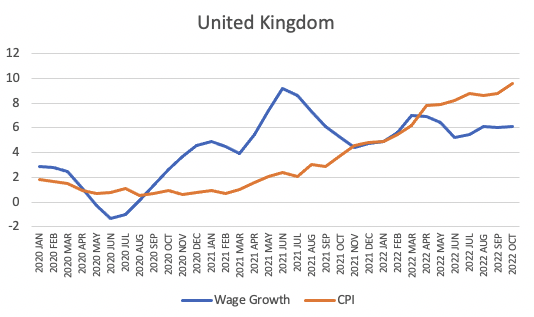

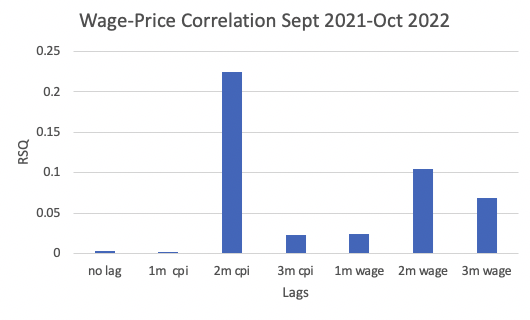

In fact, there are only two relevant questions when looking at a wage-price spiral. Firstly, did the wage rises come before or after the inflation? This can give a sense of whether wage growth had a role in sparking the initial inflation. Secondly, what are the specific dynamics taking place between wages and prices? The two charts below help us understand both.

The first chart shows clearly that large wage increases in 2021 precipitated the inflation. This does not mean that these wage increases were the only cause of inflation, but it does suggest wage growth in 2021 was a factor contributing to the present situation.

The second chart (below) shows the strength of the correlation between wages and prices adjusted for various lags. We have taken the data from September 2021 onwards, as this is when the serious inflation started. This may sound confusing, but what the chart shows is simple enough: wages tend to rise two months after an increase in inflation; then, two months after this rise in wages, prices also go up. These dynamics are clear evidence that a wage-price spiral is taking hold in the British economy.

What then of Lord Macpherson’s claim that public sector workers cannot create inflation? While it is true that, say, the NHS will not raise prices in response to higher wage demands by workers, nevertheless these higher wages will bid up the price of goods more generally. More importantly, rising wages in the public sector mean that private sector workers will demand higher pay to keep up.

The outcome of this mess is obvious: we have been here before. In the 1970s, Britain’s economy became embroiled in strikes during a period of high inflation. As time went on, the link between the two became obvious, public support of the unions withered, Margaret Thatcher was elected and the unions were defeated. Already, public support for the strikes is waning — net support has fallen from 19% in September to -3% in December. The government understands this, with one senior Conservative telling the Financial Times that public support for strikes “tends to fall the longer they go on”.

Former public officials and Left-leaning economists engaged in wage-price denialism may believe that they are protecting the working class, but they are not. Workers never win when wage-price spirals take hold for the simple reason that companies can raise prices much more easily than workers can raise wages, and so inflation-adjusted wages always fall.

In the longer term, the industrial disputes that wage-price spirals give rise to discredit unions in the eyes of the public and pave the way for laws that curtail their activity and diminish their power. The supposed experts in denial are not the champions of the working class and of working-class institutions: they are their gravediggers.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeWhat are people supposed to do if living standards are going down? If workers aren’t supposed to demand higher wages if the cost of living is going up are they just supposed to default on their bills? Not many people have significant savings to dip in to. But large numbers of people simply failing to pay rent or heating charges, or defaulting on mortgages, is also going to have repercussions.

Superficially your description seems like “workers must not demand to be paid more, even if they (unusually) have the clout to do so, because it drives inflation” but “it is a fact of nature that if workers are paid more then businesses will charge more”. If that is true, why is a demand to maintain (or improve) their living standards irresponsible for workers but not for shareholders? It takes both sides to cause a price spiral, and if labour is told to exercise restraint but capital is assumed not to be able to exercise restraint, this looks more like a statement about who is in power than anything else.

Are there any policies in favour of the labour interest (or non asset-owners) that you do think work? If people aren’t supposed to take action themselves then they would have to rely on government intervention, but that doesn’t look very reliable, and it isn’t as if the government or central banks are likely to be on their side anyway: we have had a decade or more of asset inflation through monetary policies to benefit and protect asset owners, and it seems pretty clear that things that might drive costs down, like housing reform, are pretty much off the table.

(I accept that “actually we are in a total mess and everyone’s life is just going to get worse” may be the truth, but in that context I’m not sure why it’s wrong for members of a union to do their best to get whatever they can right now. I suppose it may still be doing positive harm to give people the impression that things can be made OK by paying people a bit more, when actually our problems are far, far worse than that.)

What are people supposed to do if living standards are going down? If workers aren’t supposed to demand higher wages if the cost of living is going up are they just supposed to default on their bills? Not many people have significant savings to dip in to. But large numbers of people simply failing to pay rent or heating charges, or defaulting on mortgages, is also going to have repercussions.

Superficially your description seems like “workers must not demand to be paid more, even if they (unusually) have the clout to do so, because it drives inflation” but “it is a fact of nature that if workers are paid more then businesses will charge more”. If that is true, why is a demand to maintain (or improve) their living standards irresponsible for workers but not for shareholders? It takes both sides to cause a price spiral, and if labour is told to exercise restraint but capital is assumed not to be able to exercise restraint, this looks more like a statement about who is in power than anything else.

Are there any policies in favour of the labour interest (or non asset-owners) that you do think work? If people aren’t supposed to take action themselves then they would have to rely on government intervention, but that doesn’t look very reliable, and it isn’t as if the government or central banks are likely to be on their side anyway: we have had a decade or more of asset inflation through monetary policies to benefit and protect asset owners, and it seems pretty clear that things that might drive costs down, like housing reform, are pretty much off the table.

(I accept that “actually we are in a total mess and everyone’s life is just going to get worse” may be the truth, but in that context I’m not sure why it’s wrong for members of a union to do their best to get whatever they can right now. I suppose it may still be doing positive harm to give people the impression that things can be made OK by paying people a bit more, when actually our problems are far, far worse than that.)

Convenient how it’s never the right time for the plebs to get a raise.

Convenient how it’s never the right time for the plebs to get a raise.

Wishful thinking.

Firstly the lesson of the 70s is the public will blame the Govt. Ask Heath or Callaghan.

Secondly with public sector wage growth median at 2-3% and inflation at 10% the contention workers are being unreasonable and prompting more inflation doesn’t hold. In fact BoE forecasting a return to 2% inflation or less within 2 yrs so not indicating a real fear of wage-price spiral. There is thus scope for some more reasonable offers to settle things and not create a greater economic ‘hit’. Remember nurses are currently poorer in real terms than they were when Tories came to power.

More spotlight should be turned on the policies last 10+ yrs that allowed asset wealth to rise so much faster, increasing inequality, benefitting the better off, and leaving many public sector workers unable to afford their own home. One always suspects articles like this semi-designed to deflect away from this to protect vested interests.

Wishful thinking.

Firstly the lesson of the 70s is the public will blame the Govt. Ask Heath or Callaghan.

Secondly with public sector wage growth median at 2-3% and inflation at 10% the contention workers are being unreasonable and prompting more inflation doesn’t hold. In fact BoE forecasting a return to 2% inflation or less within 2 yrs so not indicating a real fear of wage-price spiral. There is thus scope for some more reasonable offers to settle things and not create a greater economic ‘hit’. Remember nurses are currently poorer in real terms than they were when Tories came to power.

More spotlight should be turned on the policies last 10+ yrs that allowed asset wealth to rise so much faster, increasing inequality, benefitting the better off, and leaving many public sector workers unable to afford their own home. One always suspects articles like this semi-designed to deflect away from this to protect vested interests.

To the extent that Lord Macpherson or his former close colleagues are in receipt of a DB pension linked to the pay of current civil servants, surely he has skin in the game? It seems remarkable, and rather disingenuous, that a former Permanent Secretary to the Treasury would whip up fears on social media that “HMG is expecting public sector workers to take bigger real wage cuts even than in 1931”. Then, public service pay was actively cut by 10% and more, from levels far lower in real terms than today (when public servants actually enjoy higher pay than private sector workers despite also having greater job security and better pensions). Lord Macpherson might more profitably reconsider the historic Treasury and interest rate policies which have left the economy in these straitened circumstances.

To the extent that Lord Macpherson or his former close colleagues are in receipt of a DB pension linked to the pay of current civil servants, surely he has skin in the game? It seems remarkable, and rather disingenuous, that a former Permanent Secretary to the Treasury would whip up fears on social media that “HMG is expecting public sector workers to take bigger real wage cuts even than in 1931”. Then, public service pay was actively cut by 10% and more, from levels far lower in real terms than today (when public servants actually enjoy higher pay than private sector workers despite also having greater job security and better pensions). Lord Macpherson might more profitably reconsider the historic Treasury and interest rate policies which have left the economy in these straitened circumstances.

I think it’s pretty clear what caused inflation – shutting down the global economy and pulverizing the supply chain. It was amplified by the war in the Ukraine and the energy crisis.

Both of these were self-inflicted wounds caused by weak political leaders. To expect these same people to solve the problem is a rainbow unicorn deluded fantasy.

The supply chain appears to be recovering, but the west is clueless about energy. Without serious efforts to increase domestic energy production, high energy prices could derail any efforts to reduce inflation.

Having said that, the wage-price spiral is real and could extend inflation even longer. I’m not sure what the answer is, but it surely isn’t across the board wage increases.

Yes, but don’t forget Brexit. Voluntarily cutting ourselves off from the world’s biggest free trade bloc on our very doorstep caused labour shortages and upward pressure on prices too.

Immigration is higher now than it was in the EU days, and the free trade agreement with the EU means the bulk of UK exports have no tariffs attached. So perhaps leaving the EU has had almost no effect on prices?

Maybe Brexit didn’t help, but as an explanation it’s rather weak when plenty of EU countries are suffering similar levels of inflation. So is the US, which abondoned its European overlords over 200 years ago.

Immigration is higher now than it was in the EU days, and the free trade agreement with the EU means the bulk of UK exports have no tariffs attached. So perhaps leaving the EU has had almost no effect on prices?

Maybe Brexit didn’t help, but as an explanation it’s rather weak when plenty of EU countries are suffering similar levels of inflation. So is the US, which abondoned its European overlords over 200 years ago.

Yes, but don’t forget Brexit. Voluntarily cutting ourselves off from the world’s biggest free trade bloc on our very doorstep caused labour shortages and upward pressure on prices too.

I think it’s pretty clear what caused inflation – shutting down the global economy and pulverizing the supply chain. It was amplified by the war in the Ukraine and the energy crisis.

Both of these were self-inflicted wounds caused by weak political leaders. To expect these same people to solve the problem is a rainbow unicorn deluded fantasy.

The supply chain appears to be recovering, but the west is clueless about energy. Without serious efforts to increase domestic energy production, high energy prices could derail any efforts to reduce inflation.

Having said that, the wage-price spiral is real and could extend inflation even longer. I’m not sure what the answer is, but it surely isn’t across the board wage increases.

Those who claim (like politicians) that wage increases will adversely affect inflation, almost always have good jobs with good salaries. How can it be acceptable to persist in keeping public sector wages low if it makes recruitment & retention extremely difficult? Austerity policies have eaten away at living standards for 12 years but not everyone has been getting poorer. Surely the issue of NHS staff having to access food banks is unsupportable?

Those who claim (like politicians) that wage increases will adversely affect inflation, almost always have good jobs with good salaries. How can it be acceptable to persist in keeping public sector wages low if it makes recruitment & retention extremely difficult? Austerity policies have eaten away at living standards for 12 years but not everyone has been getting poorer. Surely the issue of NHS staff having to access food banks is unsupportable?

I’m not sure what the situation is in Europe, but here in Canada public sector employees are much better paid than their private-sector counterparts. Their pensions are spectacular and their wages are higher. If there has to be belt tightening, that’s where it should start.

Not the same in the UK, at least from my experience anyway. For comparable jobs I earned much more in the private sector than I did in the public one, and while the public sector pensions were very good most have these have now been wound down.

From my limited experience, geographic locale plays a massive part due to the standardised pay structures in the public sector. This results in relatively high paying jobs in cheap living cost areas and vice versa. I also suspect that the specific role plays into this, too.

From my limited experience, geographic locale plays a massive part due to the standardised pay structures in the public sector. This results in relatively high paying jobs in cheap living cost areas and vice versa. I also suspect that the specific role plays into this, too.

Not the same in the UK, at least from my experience anyway. For comparable jobs I earned much more in the private sector than I did in the public one, and while the public sector pensions were very good most have these have now been wound down.

I’m not sure what the situation is in Europe, but here in Canada public sector employees are much better paid than their private-sector counterparts. Their pensions are spectacular and their wages are higher. If there has to be belt tightening, that’s where it should start.

So inflation took off long before wages started rising and businesses are announcing record profits, yet the workers are the ones supposed to accept a drop in their standard of living to bring inflation down?

Why not simply allow wages to rise? At the moment there is incredibly low unemployment, so let the salaries of workers rocket up. These increased salaries will cause some of the more poorly run businesses to fail, unemployment will climb and workers will no longer be able to demand more pay and wages will settle at their new level. It’ll all steady down, inflation will flatten (if workers wages are indeed the cause of it) and the nations productivity will have improved by destroying the zombie companies.

Funny how many free marketeers are only in favour of supply and demand when it’s being used to suppress wages, rather than reducing company profits

So inflation took off long before wages started rising and businesses are announcing record profits, yet the workers are the ones supposed to accept a drop in their standard of living to bring inflation down?

Why not simply allow wages to rise? At the moment there is incredibly low unemployment, so let the salaries of workers rocket up. These increased salaries will cause some of the more poorly run businesses to fail, unemployment will climb and workers will no longer be able to demand more pay and wages will settle at their new level. It’ll all steady down, inflation will flatten (if workers wages are indeed the cause of it) and the nations productivity will have improved by destroying the zombie companies.

Funny how many free marketeers are only in favour of supply and demand when it’s being used to suppress wages, rather than reducing company profits

When comparing public and private sector pay, public sector pensions, including police and fire service, must be taken into consideration. A full pension can be paid after 40 years’ service, which is why many public service workers in their mid-50s did not return to work after lockdown..

I would suggest that contracts of employment should be binding. Any salary increase should be by negotiation (decisions taken by a Board with mixed abilities and political viewpoints) and not by striking and blackmailing the government into submission.

When comparing public and private sector pay, public sector pensions, including police and fire service, must be taken into consideration. A full pension can be paid after 40 years’ service, which is why many public service workers in their mid-50s did not return to work after lockdown..

I would suggest that contracts of employment should be binding. Any salary increase should be by negotiation (decisions taken by a Board with mixed abilities and political viewpoints) and not by striking and blackmailing the government into submission.

Some countries (e.g. Australia) have high inflation and no wage growth. This round of inflation seems to relate more to years of QE, the energy situation, supply chain, etc. than to wages.

Some countries (e.g. Australia) have high inflation and no wage growth. This round of inflation seems to relate more to years of QE, the energy situation, supply chain, etc. than to wages.

This is a supply side issue, the government must be focused on addressing that. Money alone will not magic more energy and food out of thin air.

And while I agree that leaving a large proportion of the work force on a real world shrinking salary is untenable, this solution is just kicking the can down the road.

To elucidate my point, money is not directly convertible into energy and food. These require raw resources, labour and infrastructure to exploit. Successive governments have considered these to be either unimportant or problems that the market will address. And even if the market can address these issues, it will do so with severe regulatory restrictions (particularly where energy is concerned). The complete lack of redundancy* in essential requirements for our economy is a damning indictment on our political class and the media that should be keeping them in check.

*Redundancy is essential in complex systems because it prevents single points of failure. It is astonishing how reliant the west was on two single points of failure: Russia for natural gas and China for its industrial base.

This is a supply side issue, the government must be focused on addressing that. Money alone will not magic more energy and food out of thin air.

And while I agree that leaving a large proportion of the work force on a real world shrinking salary is untenable, this solution is just kicking the can down the road.

To elucidate my point, money is not directly convertible into energy and food. These require raw resources, labour and infrastructure to exploit. Successive governments have considered these to be either unimportant or problems that the market will address. And even if the market can address these issues, it will do so with severe regulatory restrictions (particularly where energy is concerned). The complete lack of redundancy* in essential requirements for our economy is a damning indictment on our political class and the media that should be keeping them in check.

*Redundancy is essential in complex systems because it prevents single points of failure. It is astonishing how reliant the west was on two single points of failure: Russia for natural gas and China for its industrial base.

Funny how it’s always described as a ‘wage-price spiral’ and never a ‘price-wage spiral’.

Funny how it’s always described as a ‘wage-price spiral’ and never a ‘price-wage spiral’.