Tuesday marked a favourite date in the calendars of think tankers and political scientists everywhere: the release of Transparency International’s annual “Corruption Perceptions” index. The index throws up interesting results every year, but the ranking for 2022 takes on particular significance amid heated debate over Ukraine’s EU aspirations.

Some of the index’s results are decidedly odd, such as the Czech Republic ranking one place below Qatar, despite allegations that the Gulf state has been operating an international bribery network to buy the favour of EU politicians.

But surveying Europe’s results as a whole, perhaps the most interesting finding is that Ukraine and Russia sit together at the top of the corruption league table. President Volodymyr Zelensky has been on an anti-corruption drive ahead this week’s EU summit, in which he hopes to impress Brussels leaders. Already, though, Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, has warned that EU membership is ‘a long way off’ for Ukraine. After 10 high-level resignations last week, Zelensky launched another round where the houses of billionaire oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky and former interior minister Arsen Avakov were searched.

Zelensky is eager to prove to EU leaders that he is unafraid to root out corruption in the highest ranks, and Transparency International points out that, unlike Russia, perceptions of Ukraine are on an upward curve.

But corruption is a long-standing issue and remains arguably the biggest stumbling block to Ukraine’s aspirations to become a fully-fledged member of the Western international order. Zelensky is showing determination to change perceptions, but it doesn’t help that prior to Russia’s invasion, the President himself was accused of corrupt relations with Kolomoisky.

The issue has been put on the backburner amid a determination to support Ukraine’s war effort. But especially in some Eastern European countries such as Hungary and the Czech Republic, stereotypes of corruption in Ukraine are deeply ingrained among large swathes of the public.

Transparency International’s index suggests that the same is true for the “experts and businesspeople” who provide data for the rankings. This is concerning for Ukraine, because a persistently low score in “the most widely used global corruption ranking in the world” is likely to be cited by EU leaders who remain deeply concerned about cutting corners in the country’s accession negotiations.

Russia’s even lower score is no surprise, and the country has hovered at around the same level for years: Transparency International describes Russia as “the very embodiment of a kleptocracy”. Specific motivations for Russia’s downgrading this year are left vague, with most of the focus on the international impact of Putin’s aggression. But the Kremlin’s suppression of war critics and a string of mysterious deaths of business leaders in 2022 can’t have helped.

It should be remembered that Transparency International’s index is based on subjective opinions, so its results shouldn’t necessarily be taken as sacrosanct. But in the context of war in Ukraine, the fact that perceptions of corruption continue to dog Kyiv takes on a new significance. With EU leaders meeting Zelensky this week to discuss Ukraine’s future, this ranking may provide ammunition for those arguing that Ukraine is still years — potentially decades — away from meeting their conditions for membership.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeHaha, so what’s the odd $ 100 Billion, no audit naturally, up to? Well….. My guess is the depths of depravity and corruption involved could never be believed if exposed, too crazy – and we know that is not happening anyway.

FTX was up to some wild stuff so Bankman-Fried has about 1 in 1000 chance of surviving his sentence, Hunter??? Without secret Service he would be pretty worried now – but drop in the bucket….This Regional Conflict Biden has turned into WWIII is Nothing to do with freedom and democracy – it is all Power, energy, $ and some terrifying NWO thing. Corruption is the wheels this juggernaut rides on. MSM and Social Media Lies are the engine driving it.

Did you see the meeting just now of Ursula von der Leyen and Zalenski? And the recent one of Boris and him meeting? Red Carpets – long walk with cameras set on to Hollywood slickness – eyes full of stars, hands clasped at least 10 seconds more than than decency would expect – these guys are teamed up….. This is a wild time, anyone think this is about ‘Democracy’ likely thinks Lockdowns saved the world……

Haha, so what’s the odd $ 100 Billion, no audit naturally, up to? Well….. My guess is the depths of depravity and corruption involved could never be believed if exposed, too crazy – and we know that is not happening anyway.

FTX was up to some wild stuff so Bankman-Fried has about 1 in 1000 chance of surviving his sentence, Hunter??? Without secret Service he would be pretty worried now – but drop in the bucket….This Regional Conflict Biden has turned into WWIII is Nothing to do with freedom and democracy – it is all Power, energy, $ and some terrifying NWO thing. Corruption is the wheels this juggernaut rides on. MSM and Social Media Lies are the engine driving it.

Did you see the meeting just now of Ursula von der Leyen and Zalenski? And the recent one of Boris and him meeting? Red Carpets – long walk with cameras set on to Hollywood slickness – eyes full of stars, hands clasped at least 10 seconds more than than decency would expect – these guys are teamed up….. This is a wild time, anyone think this is about ‘Democracy’ likely thinks Lockdowns saved the world……

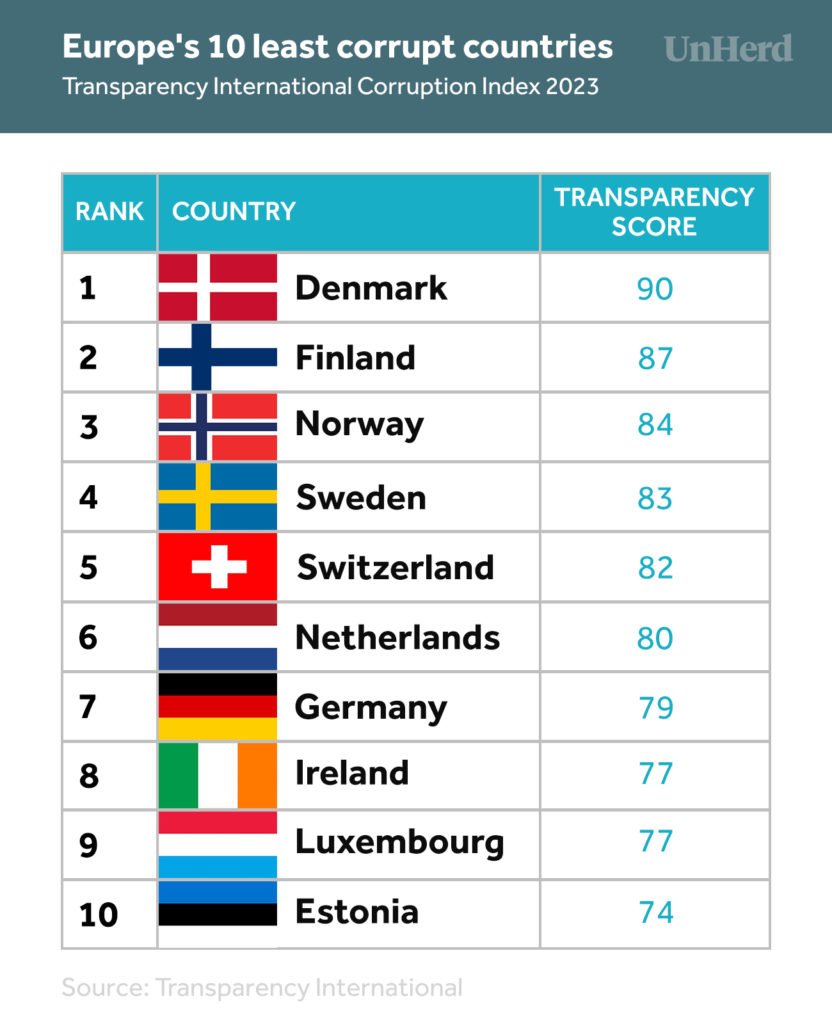

The placing of Ireland as 8th least corrupt state proves how useless a perception based survey is. There’s been successive waves of corruption scandals here since the 60s. There’s a few ongoing right now

The placing of Ireland as 8th least corrupt state proves how useless a perception based survey is. There’s been successive waves of corruption scandals here since the 60s. There’s a few ongoing right now

Nothing new here. Russia and Ukraine have been 1st and 2nd in Europe for years, probably since TI have published this index.

Funny how it took a visit from the CIA director to Kiev recently to kick start an anti-corruption drive when Zelensky has been in power for three years. He must have been told to clean up his act if he wants to keep those weapons and $$$ flowing.

Nothing new here. Russia and Ukraine have been 1st and 2nd in Europe for years, probably since TI have published this index.

Funny how it took a visit from the CIA director to Kiev recently to kick start an anti-corruption drive when Zelensky has been in power for three years. He must have been told to clean up his act if he wants to keep those weapons and $$$ flowing.

Switzerland has the fifth place as the least corrupt country? That must be a joke, a country that eagerly receives funds from whatever dictator or rouge country in the world isn’t corrupt? FIFA is probably the most corrupt of them all.

Switzerland has the fifth place as the least corrupt country? That must be a joke, a country that eagerly receives funds from whatever dictator or rouge country in the world isn’t corrupt? FIFA is probably the most corrupt of them all.

Note that this index is based on ‘subjective opinions’ and ‘perceptions’ not data and evidence. Ukraine was undoubtedly a gangster-dominated, corrupt society when under the influence of the Russian kleptocracy but Zelenskiy was elected (fairly unless you have concrete evidence to the contrary and not just Russian smears), only 3 years ago, on an anti-corruption ticket. It seems that also the war has changed everything in that regard and I maybe naive but if slow rooting out of corruption is very tricky, if not nearly impossible, the invasion by a Russian state on a killing spree is the seismic event which should sort it out, as seems to be happening.

Zelensky ran on a platform of peace. That he would help end the war and bring peace in the breakaway Donetsk regions, and adhere to the Minsk aggrements, even on expanding rights and protections to native Russian speakers (like himself) in schools. He had a lot of good promises…

And corruptly failed to honour a single one.

And corruptly failed to honour a single one.

Zelensky ran on a platform of peace. That he would help end the war and bring peace in the breakaway Donetsk regions, and adhere to the Minsk aggrements, even on expanding rights and protections to native Russian speakers (like himself) in schools. He had a lot of good promises…

Note that this index is based on ‘subjective opinions’ and ‘perceptions’ not data and evidence. Ukraine was undoubtedly a gangster-dominated, corrupt society when under the influence of the Russian kleptocracy but Zelenskiy was elected (fairly unless you have concrete evidence to the contrary and not just Russian smears), only 3 years ago, on an anti-corruption ticket. It seems that also the war has changed everything in that regard and I maybe naive but if slow rooting out of corruption is very tricky, if not nearly impossible, the invasion by a Russian state on a killing spree is the seismic event which should sort it out, as seems to be happening.

No wonder Ukraine is on the top of the list considering the amount of corrupt russians currently occupying parts of country.

Ukraine has been the Clinton, Obama, and Biden Piggy Bank for ever. Remember the 10% for the big guy? That is what Zalensky has tattooed over his heart, same as Biden.

Ukraine has been the Clinton, Obama, and Biden Piggy Bank for ever. Remember the 10% for the big guy? That is what Zalensky has tattooed over his heart, same as Biden.

No wonder Ukraine is on the top of the list considering the amount of corrupt russians currently occupying parts of country.

Russian criminal gangs in the Donbas are to blame for much of this. They have links to their pals in Ukainre.

Dream on.

Really this war should be over now. Zelensky was talking about accepting neutrality, but Borris came in on behalf of the Biden admin and said “under no circumstances”. This war is out of control, pushed on by those who don’t see themselves as having anything to lose. The worst thing is that the further East you go, the worse the Ukranian equipment is. It’s like thier lives dont even matter. But isn’t this the story all over the world now. Do any of the lives of people really matter to those in charge?

To most of them, no. You would like to think that the answer was yes, but while the governments change the anti-human policies stay the same. In the western world most of our leaders think that we are too well off and need a bit of poverty or at least the threat, to sharpen our attitudes and enforce our compliance.

To most of them, no. You would like to think that the answer was yes, but while the governments change the anti-human policies stay the same. In the western world most of our leaders think that we are too well off and need a bit of poverty or at least the threat, to sharpen our attitudes and enforce our compliance.

Dream on.

Really this war should be over now. Zelensky was talking about accepting neutrality, but Borris came in on behalf of the Biden admin and said “under no circumstances”. This war is out of control, pushed on by those who don’t see themselves as having anything to lose. The worst thing is that the further East you go, the worse the Ukranian equipment is. It’s like thier lives dont even matter. But isn’t this the story all over the world now. Do any of the lives of people really matter to those in charge?

Russian criminal gangs in the Donbas are to blame for much of this. They have links to their pals in Ukainre.