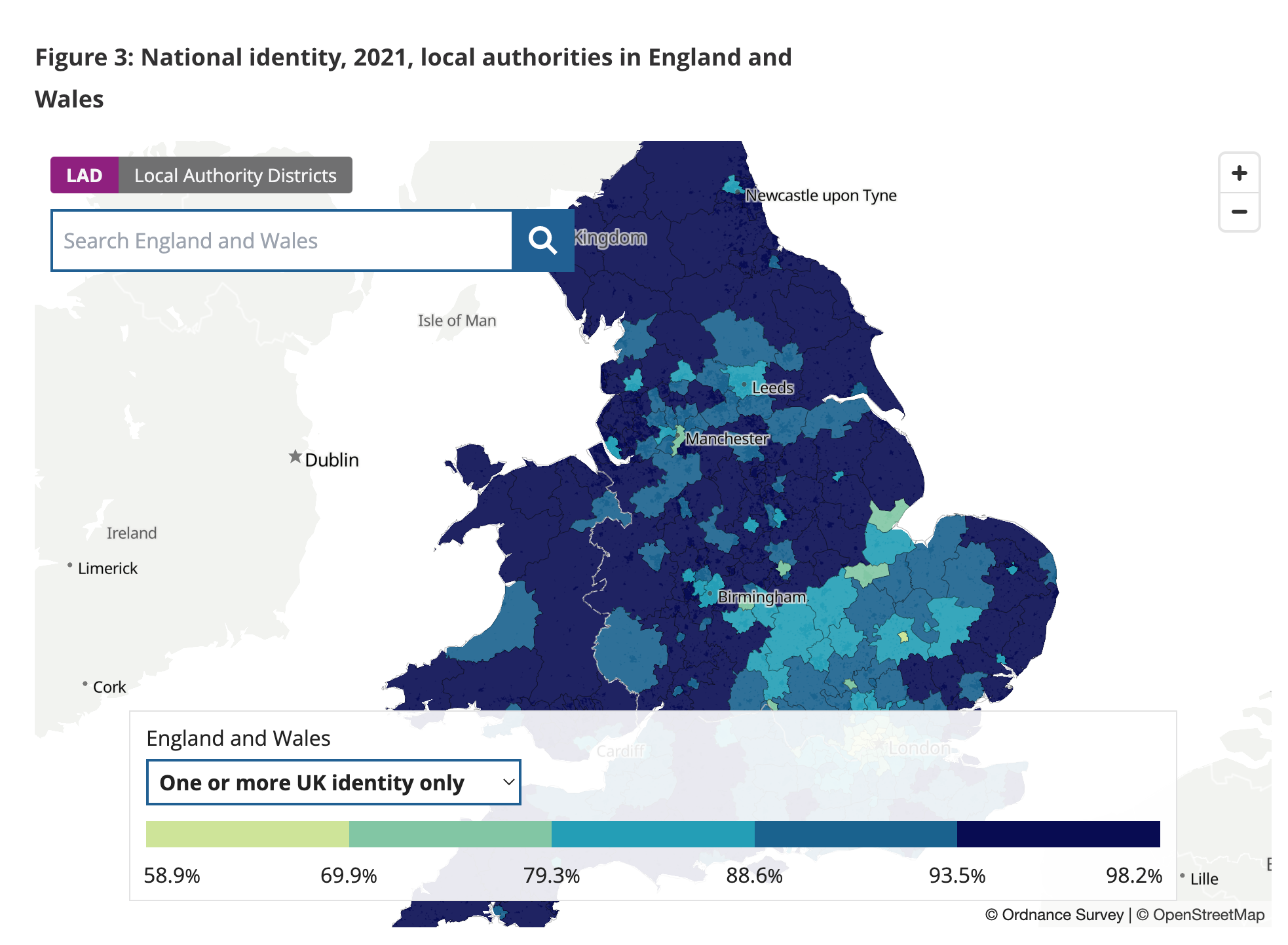

The release of census data on national identity should have demonstrated our progress towards a shared sense of nation. Sadly, it doesn’t shed much light on who we think we are, nor what it means. Flawed questions created a largely illusory swing from 60% ‘English only’ in 2011 to 55% ‘British only’ last year (reputable surveys show a much more gradual shift). This hasn’t stopped the ONS promoting a misleading ‘interactive map’ with only the vaguest health warning.

And when England’s diverse footballers take on Wales tonight, none of them could have ticked ‘Black English’, while the Welsh census let people be Black Welsh. The Welsh government insisted on the choice, while England’s union state did not. Excluding England’s ethnic minorities — you couldn’t be Asian English either — from English national identity and only letting them be British sends a powerful and unpleasant message about who belongs to the national community and who does not, as Labour’s David Lammy has highlighted.

Sloppy data gathering and presentation is indicative of scant interest in the extent to which we have shared national identities. Immigration is back at the centre of debate, but we need to be asking what nation is being made from those people already here. One in six of England’s residents were born outside the UK, with 4.2 million coming in the past ten years, 2.7 million between 2001 and 2011 and 3.6 million before that. Many who are making their lives here still feel no UK identity: this is a sweeping re-shaping of a national population. While there is no reason to think we can’t make a success of it — indeed we have no choice — it would be dangerous to assume that we will.

At one level things are going perfectly well. Our Prime Minister is a second-generation migrant, and Tory unpopularity owes little to his ethnicity. But the loose ties of liberal tolerance do not foster the shared stories, shared belonging, and shared commitments to each other that all nations will need in a world of climate change, food insecurity, mass migration and competition for energy and raw materials.

What’s more, this is a world in which the threshold of war has been lowered, human rights diminished, and democracy threatened. Only societies with the cohesion and common purpose that stem from a strong sense of nationhood and national belonging will give security to their own citizens and be the building blocks of internationalism. For those of us in England, that nationhood will be both English and British.

Conservative Unionists might want Britishness to unite the UK, but it doesn’t. The cosmopolitan Britishness of England’s elites is quite different to more English forms of Britishness. The British Election Study data shows people with strong English identities are much less diverse. National democracy and sovereignty have different meanings to different identities. In short, we don’t agree which nation we belong to or what that nation means. The contested understandings of national identity muddled by the census could yet become political fracture lines as they have in the recent past. At the very least, the offer they make to our newer fellow citizens is unwelcoming and confused.

British multiculturalism was buried by David Cameron ten years ago and popular Englishness, hidden from sight except in sport, has always had to make its own, as yet incomplete, journey to reflect all of England. (A good World Cup always helps). Rather than face the future with complacency, we would do better to understand that cohesive nations don’t build themselves.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeThe more I see stuff like this, the more I think our elites have become increasingly anti-English. Ideally I don’t want to give weight to things like the Great Replacement Theory, but it is becoming harder to not see the logical dots joining together.

It’s not anti-English, per se, but anti-religion, anti-culture, anti-spirituality, anti-self – anything to dislodge people from their roots and their traditions in order to replace these with the controlling slave morality of existence-guilt (i.e. you belong to an oppressor class so whatever bad things we do to you are well-deserved), and the false freedom of sexual licentiousness which serves well as a distraction while civil liberties and institutions are being quietly dismantled.

If it looks like a duck, walks like a duck and quacks like a duck it is probably….something else entirely a don’t say any different

It’s not anti-English, per se, but anti-religion, anti-culture, anti-spirituality, anti-self – anything to dislodge people from their roots and their traditions in order to replace these with the controlling slave morality of existence-guilt (i.e. you belong to an oppressor class so whatever bad things we do to you are well-deserved), and the false freedom of sexual licentiousness which serves well as a distraction while civil liberties and institutions are being quietly dismantled.

If it looks like a duck, walks like a duck and quacks like a duck it is probably….something else entirely a don’t say any different

The more I see stuff like this, the more I think our elites have become increasingly anti-English. Ideally I don’t want to give weight to things like the Great Replacement Theory, but it is becoming harder to not see the logical dots joining together.

The essence of being English is that we rely on effortless superiority, always have done and always will. In short we don’t need the ‘noise’ of lesser breeds as Mr Kipling rather unkindly called them.

However self praise is “no recommendation” so let us hear from a distinguished Spanish philosopher, who even had the misfortune to teach at Harvard, the late Georges Santayana.

This what he said about the British Empire in 1912, and off course he regarded it as an English Empire.

: “Never since the heroic days of Greece has the world had such a sweet, just, boyish master. It will be a black day for the human race when scientific blackguards, conspirators, churls, and fanatics manage to supplant him”.

Good man, and praise indeed from such an unbiased source is it not?

And from the same piece:

“Instinctively the Englishman is no missionary, no conqueror. He prefers the country to the town, and home to foreign parts.”

Those in the former ‘empire’ may disaver with his view of the English. Interesting that you’ve labelled it English, like the SNP, thereby letting us celts off the hook for its negative aspects.

I never forget my lovely Guards Depot PTI Lance S’arnt Kelly saying .. ” Your name is too complicated.. from now on you are ” Sooty’! It was just so funny… and I so loved and respected him too!

Please try to make your stories a little bit more realistic. More fun for the rest of us when they aren’t obviously complete nonsense.

Please try to make your stories a little bit more realistic. More fun for the rest of us when they aren’t obviously complete nonsense.

“Off” course he did, old chap! Is that an example of your English effortless superiority – the misspelling of a two letter word?

Nobody uses the term English Empire other than the most pathological twit. Of course, anyone with any actual knowledge of the British Empire knows that it was primarily won and run by Scots with a few Irish helping out. The English mainly swanned around and got in the way at inopportune moments, the list of which is long.

And from the same piece:

“Instinctively the Englishman is no missionary, no conqueror. He prefers the country to the town, and home to foreign parts.”

Those in the former ‘empire’ may disaver with his view of the English. Interesting that you’ve labelled it English, like the SNP, thereby letting us celts off the hook for its negative aspects.

I never forget my lovely Guards Depot PTI Lance S’arnt Kelly saying .. ” Your name is too complicated.. from now on you are ” Sooty’! It was just so funny… and I so loved and respected him too!

“Off” course he did, old chap! Is that an example of your English effortless superiority – the misspelling of a two letter word?

Nobody uses the term English Empire other than the most pathological twit. Of course, anyone with any actual knowledge of the British Empire knows that it was primarily won and run by Scots with a few Irish helping out. The English mainly swanned around and got in the way at inopportune moments, the list of which is long.

The essence of being English is that we rely on effortless superiority, always have done and always will. In short we don’t need the ‘noise’ of lesser breeds as Mr Kipling rather unkindly called them.

However self praise is “no recommendation” so let us hear from a distinguished Spanish philosopher, who even had the misfortune to teach at Harvard, the late Georges Santayana.

This what he said about the British Empire in 1912, and off course he regarded it as an English Empire.

: “Never since the heroic days of Greece has the world had such a sweet, just, boyish master. It will be a black day for the human race when scientific blackguards, conspirators, churls, and fanatics manage to supplant him”.

Good man, and praise indeed from such an unbiased source is it not?

I’ve always regarded it as a sign of strength that we don’t (need) to make a big issue of English identity. The direct comparison with todays article about Welsh identity is telling and whilst the medium of football is cited in both articles as helping define who we are, the Welsh exhortation to national identity is something the English generally eschew.

I’m two generations removed from Irish soil (literally) but couldn’t regard myself as being any more English than if i ran naked across an air-cooled pitch in Qatar painted in a rainbow consisting only of the red/white end of the spectrum. The day we feel the need to assert our national identity is the day we no longer have one. That day is a very long way off, if it happens at all.

We’ll absorb the current influx, though it must be curbed. But most of all, WE KNOW WHO WE ARE.

“The day we feel the need to assert our national identity is the day we no longer have one. “

Only someone ashamed of their identity contorts themselves into such nonsense. Of course you’re Irish, not English.

“The day we feel the need to assert our national identity is the day we no longer have one. “

Only someone ashamed of their identity contorts themselves into such nonsense. Of course you’re Irish, not English.

I’ve always regarded it as a sign of strength that we don’t (need) to make a big issue of English identity. The direct comparison with todays article about Welsh identity is telling and whilst the medium of football is cited in both articles as helping define who we are, the Welsh exhortation to national identity is something the English generally eschew.

I’m two generations removed from Irish soil (literally) but couldn’t regard myself as being any more English than if i ran naked across an air-cooled pitch in Qatar painted in a rainbow consisting only of the red/white end of the spectrum. The day we feel the need to assert our national identity is the day we no longer have one. That day is a very long way off, if it happens at all.

We’ll absorb the current influx, though it must be curbed. But most of all, WE KNOW WHO WE ARE.

Is there a way we can accept that race or ethnicity is important to people and connects them with history and meaning while not creating hate? It feels it’s an irrepressible truth about life and people’s sense of Nation. Can we accept this and be respectful and also see other attributes to humans?!

Is there a way we can accept that race or ethnicity is important to people and connects them with history and meaning while not creating hate? It feels it’s an irrepressible truth about life and people’s sense of Nation. Can we accept this and be respectful and also see other attributes to humans?!

Some Welsh are black.

So what?

Why is skin colour important? Why should it define anyone? Did Luther King die in vain? Isn’t the content of our character the thing?

I became a British citizen in Winchester. But I’m not English. Nor would I have become Welsh in Cardiff.

There are a lot of dual or more nationals like me with all the rights and duties of any born here. But we shouldn’t be defined by our colour.

Black skin is neither here nor there per se, but it comes with a whole different suite of genes and consequent heritable behaviours and capacities. That’s the distinction that is worth remembering.

In the fifties liberals genuinely did believe we were all the same beneath the skin so it was unreasonable to attend to it. Nowadays we know different, as a result of four decades and more of twin studies. We are much more constrained by our genetics than people admit.

Black skin is neither here nor there per se, but it comes with a whole different suite of genes and consequent heritable behaviours and capacities. That’s the distinction that is worth remembering.

In the fifties liberals genuinely did believe we were all the same beneath the skin so it was unreasonable to attend to it. Nowadays we know different, as a result of four decades and more of twin studies. We are much more constrained by our genetics than people admit.

Some Welsh are black.

So what?

Why is skin colour important? Why should it define anyone? Did Luther King die in vain? Isn’t the content of our character the thing?

I became a British citizen in Winchester. But I’m not English. Nor would I have become Welsh in Cardiff.

There are a lot of dual or more nationals like me with all the rights and duties of any born here. But we shouldn’t be defined by our colour.

My parents were both born outside the UK and are Italian and Irish: I was born here… am I ” English” ? Only in so far as I have a British passport! I have different cultural breeding, attitudes, emotions, and looks. At least I have the honesty and grace to admit it, and to love England, and the privelige, as Cecil Rhodes says ” To have been born in England and won the lottery of life.. Being born in a stable does not make one a horse.

Not only are you honest and graceful but modest too!

Not only are you honest and graceful but modest too!

My parents were both born outside the UK and are Italian and Irish: I was born here… am I ” English” ? Only in so far as I have a British passport! I have different cultural breeding, attitudes, emotions, and looks. At least I have the honesty and grace to admit it, and to love England, and the privelige, as Cecil Rhodes says ” To have been born in England and won the lottery of life.. Being born in a stable does not make one a horse.

If you can be black English aren’t you robbing something important from the English? Their national identity?

People bang on about diversity

as if it’s good but elsewhere in the world it’s a problem . Why not here? Are we so clever or good.?

If you can be black English aren’t you robbing something important from the English? Their national identity?

People bang on about diversity

as if it’s good but elsewhere in the world it’s a problem . Why not here? Are we so clever or good.?

“Why isn’t ‘black English’ a census option?”

Because it is an oxymoron, that’s why.

A person can’t be black and English? What an interesting point of view! You don’t happen to work at Buckingham Palace do you?!?!

No. I don’t work at the Palace.

But, unlike you, I am not confused as to what words mean.

Glad to help.

Your words are perfectly clear. As far as you are concerned a person can’t be black and English.

Why do you feel that way?

Your words are perfectly clear. As far as you are concerned a person can’t be black and English.

Why do you feel that way?

Being qualified to play football for England does not necessarily make one English, at least not in a deeper sense that many people will recognize.”Englishness” in this deeper sense is a mixture of shared ethnicity, kinship, history and culture.

So you, who I assume have never represented your country at anything, are more English than say, Marcus Rashford, who is out there working his bollox off to achieve something for his country?

But you are more English than him because he’s black?

Glad we got that cleared up…

So you, who I assume have never represented your country at anything, are more English than say, Marcus Rashford, who is out there working his bollox off to achieve something for his country?

But you are more English than him because he’s black?

Glad we got that cleared up…

No. I don’t work at the Palace.

But, unlike you, I am not confused as to what words mean.

Glad to help.

Being qualified to play football for England does not necessarily make one English, at least not in a deeper sense that many people will recognize.”Englishness” in this deeper sense is a mixture of shared ethnicity, kinship, history and culture.

A person can’t be black and English? What an interesting point of view! You don’t happen to work at Buckingham Palace do you?!?!

“Why isn’t ‘black English’ a census option?”

Because it is an oxymoron, that’s why.

Melanie Phillips has posted a fine essay on her substack on this subject.

https://melaniephillips.substack.com/p/an-altered-state

Melanie Phillips has posted a fine essay on her substack on this subject.

https://melaniephillips.substack.com/p/an-altered-state

English is an ethnicity. You can’t be black and English. Despite living all my life in England I don’t consider myself properly English, rather British, because most of my ancestry is Irish with Scottish and English mix.

This will come as a surprise to the black players currently representing England at the World Cup!

I don’t see why. An English national football team is an historical anomaly. It should be a British national team.

What on earth does that have to do with black footballers representing England?

In the context of this conversation, quite a lot.

In the context of this conversation, quite a lot.

What on earth does that have to do with black footballers representing England?

I don’t see why. An English national football team is an historical anomaly. It should be a British national team.

How far do you have to go back in your ancestry to be English? The Romans? If you are black, brown or pale pink and your ancestors came from somewhere else to settle in any nation in GB, and you are born here, you are of that country. So if, for example, your great grandparents came from the Caribbean to England, Scotland or Wales and you were born in any of these countries, you can rightly call yourself either Black English, Black Scottish or Black Welsh as well as Black British Just as I call myself White Scottish and White British. Anything else is racist.

This will come as a surprise to the black players currently representing England at the World Cup!

How far do you have to go back in your ancestry to be English? The Romans? If you are black, brown or pale pink and your ancestors came from somewhere else to settle in any nation in GB, and you are born here, you are of that country. So if, for example, your great grandparents came from the Caribbean to England, Scotland or Wales and you were born in any of these countries, you can rightly call yourself either Black English, Black Scottish or Black Welsh as well as Black British Just as I call myself White Scottish and White British. Anything else is racist.

English is an ethnicity. You can’t be black and English. Despite living all my life in England I don’t consider myself properly English, rather British, because most of my ancestry is Irish with Scottish and English mix.

As a Scot living in England for 40 years but retaining a strong accent, it always amuses me that English people assume I’ll support Scotland in various things including sport. But I don’t.

It seems odd to me given the general pursuit of immigrant integration, with English born Asians often criticised for supporting the country of their heritage, that ‘native’ English can’t accept a Scotsman might support England, even against Scotland.

It also amuses me that English people will make all sorts of assumptions about me because of my accent. They wouldn’t dare ask a black or Asian man where he comes from, but there’s no hesitancy in asking me. I like to tease them by asking how they could tell I’m not a local after 40 years of working on a Hampshire accent. Some of them get my joke – many don’t.

As a Scot living in England for 40 years but retaining a strong accent, it always amuses me that English people assume I’ll support Scotland in various things including sport. But I don’t.

It seems odd to me given the general pursuit of immigrant integration, with English born Asians often criticised for supporting the country of their heritage, that ‘native’ English can’t accept a Scotsman might support England, even against Scotland.

It also amuses me that English people will make all sorts of assumptions about me because of my accent. They wouldn’t dare ask a black or Asian man where he comes from, but there’s no hesitancy in asking me. I like to tease them by asking how they could tell I’m not a local after 40 years of working on a Hampshire accent. Some of them get my joke – many don’t.

I can’t speak for black people on this, but as a dual nationality resident in England with an Irish passport, I have never had any difficulty specifying that I’m British Irish as opposed to English Irish. The distinction seems a bit irrelevant as far as I’m concerned.

11

Being of Scots-English heritage (with a little Welsh in the mix), residing north of the border and ‘identifying’ as British and Scottish, the (late) 2022 Census options I found rather limiting:

The answers are Scottish, Other British, Irish, Polish, Gypsy Traveller and Roma

I am none of the above. I support all of the home nations and their athletes in sport excluding two situations:

Playing against the Scottish national team

Kneeling before the start of play

Why does the players supporting the end of racism cause you not to support a team?

They are not supporting “the end of racism” though are they? I love virtue – signalling. So much virtue at so little cost.

I’m sure that will come as a surprise to the players who have explicitly stated that they take the knee to support the fight to end racism.

Were you in the changing room when they were all laughing about how it was all just a big virtue signaling joke that they were pulling on the nation?

Or are you just the type of grumpy old geezer who uses the term “virtue signaling” about anything that annoys you, which is just about everything?

You are gullible.

Ask these players what they actually do to support the fight to end racism. I will answer for them – Nothing. Let me know when they dip their hands into their pockets, or disaccommodate themselves in some significant way.

I use the term “virtue signaling” when I see sanctimonious gestures masquerading as genuine commitment.

Glad to help.

How do you know that they don’t do anything, other than show their very public support, to support the fight to end racism? Do you have access to their personal financial records showing they make no financial contributions to the anti racism cause? Or maybe you can access their calendars showing that they spend no time supporting this cause?

Of course not. You don’t have the faintest idea – other than their very public demonstration of support – what they do or don’t do.

You use the term “virtue signaling” in the same way every other unimaginative and angry grouch uses it when you are annoyed by people trying to do the right thing because you don’t like it!

Presumably if they did do all of the above, it might be noted. After all, it would certainly embellish their credentials. In the meantime, plenty of extra money to be trousered in commercials and product endorsements.

Anyway, kneeling won’t ‘end racism’ any more than signing a petition against world hunger will feed people in famine stricken regions. Neither will playing football in one of the world’s most oppressive countries. If you care that much, don’t go.

“Presumably”? Why would you presume that? Sounds like you are judging them by your own standards.

It sounds like you know what will end racism since you are so clear about what won’t. Care to enlighten us?

“It sounds like you know what will end racism since you are so clear about what won’t. Care to enlighten us?”

Alphonse merely pointed out that making cost-free gestures in front of a camera does not end racism. Can you really not see the comic obscenity of “taking the knee” in a football stadium in Qatar, and then proceeding with the game?

Time to ditch the naivety, and learn to distinguish between action and gesture.

And remember – Always follow the money. I figured that much by the time I was ten.

“How do you know that they don’t do anything, other than show their very public support, to support the fight to end racism?”

Because their agents would have alerted the world to their good deeds.

What do we get – deafening silence.

Genetically we’re all 99.9% the same and even the genome of unrelated people only varies by 0.4-0.6%. So one suspects this racial/ethnic census type grouping will look quite strange to historians in future centuries and they’ll be puzzled by it all.

As regards defining our groupings on a more cultural (or ethnic) basis – always had and has a limited shelf life. The population of this island has always evolved and changed. What is deemed ‘English’ is fairly new and will further evolve too. We all know the truism that you can never expect to stand in the same river twice.

For amusement – Alfred the Great, never had any concept of England or Britain; William the Conqueror was obviously neither; Richard the Lionheart thought of himself as more French than English, a catholic in the 16th century would have been seen as foreign; William of Orange was of course Dutch and led the Glorious Revolution; George’s I and II were German first. And finally our own Royal Family changed its name before we cottoned on they weren’t really English. And so it’ll continue.

Perhaps more important are the values that define and bond us – that could be debated another time perhaps – tolerance, decency, belief in fair play, rule of law, democracy etc

Genetically we’re all 99.9% the same and even the genome of unrelated people only varies by 0.4-0.6%. So one suspects this racial/ethnic census type grouping will look quite strange to historians in future centuries and they’ll be puzzled by it all.

As regards defining our groupings on a more cultural (or ethnic) basis – always had and has a limited shelf life. The population of this island has always evolved and changed. What is deemed ‘English’ is fairly new and will further evolve too. We all know the truism that you can never expect to stand in the same river twice.

For amusement – Alfred the Great, never had any concept of England or Britain; William the Conqueror was obviously neither; Richard the Lionheart thought of himself as more French than English, a catholic in the 16th century would have been seen as foreign; William of Orange was of course Dutch and led the Glorious Revolution; George’s I and II were German first. And finally our own Royal Family changed its name before we cottoned on they weren’t really English. And so it’ll continue.

Perhaps more important are the values that define and bond us – that could be debated another time perhaps – tolerance, decency, belief in fair play, rule of law, democracy etc

To show our ethnic origins in a census is uneccessary … in England we are all English if born/live or have taken out citizenship … it’s a choice to be or not to be … England is about it’s people and not the colour of their skin.

What nonsense, being English is about being English, which is an ethnic group, not an idea, or a marker of having been born on a specific bit of soil.

You’ve been consuming too much american twaddle methinks.

There is no such thing as an English ethnic group. We are all a mixture. At a minimum I have Scottish & French ancestors (and probably Viking & Norman as well) along with Anglo-Saxon and possibly more. I am English (and not British) because that is my culture. Anyone else who shares that culture and attachment to England is welcome to call themselves English.

I think you have been influenced by Germanic twaddle.

…and that range of mixtures is what makes up the English ethnicity.

It’s curious that you have no problems referring to Scottish, French, Anglo-Saxon, Viking or Norman as ethnic groups, but apparently calling the English an ethnic group is too far.

I’ll never understand westerners that seem ashamed/unwilling to accept that they belong to an ethnic group. Apparently that’s a thing for “other people”.

It must be that damned word RACE, which everyone gets so excited about.

However we all a mixture, a Whiskey & Soda so to speak.

Take the French, a combination of Gallic nutters of the Asterix variety combined with a very large dose of Frankish ( German…heaven forbid) thugs, with some Nordic marauders otherwise known as Vikings thrown in for good measure.

Off course it is slightly worse for the poor old Germans, as the Mongolian/Hunnish element is still occasionally visible.

…no doubt explaining why Kipling slightingly referred to those poor old Germans as ‘lesser breeds without the law’.

Another guy who hasn’t actually read Kipling.

Another guy who hasn’t actually read Kipling.

No less than 3 senior Officers in The Coldstream at the moment with Italian surnames!!

There used to be quite a few in the Welsh Guards, otherwise known as the Foreign Legion.

absolutely, and one, a great mate, who commanded in Afghanistan!

absolutely, and one, a great mate, who commanded in Afghanistan!

There used to be quite a few in the Welsh Guards, otherwise known as the Foreign Legion.

Whiskey? Oh dear, oh dear, it seems like our English chum prefers his tipple mixed in a Kentucky bathtub or perhaps a Manitoban grain elevator!

No surprise that an Englishman has poor taste when it comes to whisky. No doubt reflected in his other lifestyle choices – one shudders to think of it…

…no doubt explaining why Kipling slightingly referred to those poor old Germans as ‘lesser breeds without the law’.

No less than 3 senior Officers in The Coldstream at the moment with Italian surnames!!

Whiskey? Oh dear, oh dear, it seems like our English chum prefers his tipple mixed in a Kentucky bathtub or perhaps a Manitoban grain elevator!

No surprise that an Englishman has poor taste when it comes to whisky. No doubt reflected in his other lifestyle choices – one shudders to think of it…

Scottish people are no more a homogenous group than any other in terms of ethnicity. The SNP Government and their nationalists do not speak for everyone in Scotland and we don’t all think the same, nor do we all eat the same food, or have the same language. Ethnicity is no longer what makes us gel together if it ever did nor does it make for one people, another myth perpetuated by people in power.

It must be that damned word RACE, which everyone gets so excited about.

However we all a mixture, a Whiskey & Soda so to speak.

Take the French, a combination of Gallic nutters of the Asterix variety combined with a very large dose of Frankish ( German…heaven forbid) thugs, with some Nordic marauders otherwise known as Vikings thrown in for good measure.

Off course it is slightly worse for the poor old Germans, as the Mongolian/Hunnish element is still occasionally visible.

Scottish people are no more a homogenous group than any other in terms of ethnicity. The SNP Government and their nationalists do not speak for everyone in Scotland and we don’t all think the same, nor do we all eat the same food, or have the same language. Ethnicity is no longer what makes us gel together if it ever did nor does it make for one people, another myth perpetuated by people in power.

Yes I think you have a very good point here. Rather have people from diverse origins who embrace English culture, than Woke people of Caucasian origin who are predominantly ashamed of it.

I suspect the vast majority of us whose ancestors were here in the mid 19th century are Celtic/Anglo Saxon in origin ( the mixture seems to me to be undeniable given the nature of the Anglo Saxon invasions ) and possibly pre Celtic also . Some Viking also but as the Normans were an imposed ruling class I doubt if many of us have much Norman ancestry. To me that looks like a specific identity much as the progressives deplore this.

Every other nation is given the courtesy of a national identity rooted in the land and the history of it’s people . Just look at the current love affair of the left with the Ukrainians. .

We English need that courtesy as well . Hard though it is for the progressive herd to countenance this.

Spot on, English is the land and culture to which you belong; it matters not what your ethnicity is, only where your loyalties lie. Like you I know that I have non-English genes (my mother was Scottish), but I was born and raised in England and it’s to England that I owe my loyalties (Britain is second in my loyalties)

Civis Romanus sum, is the best example is it not?

You will be amused to hear that my reply to you, quoting Cicero, has been ‘zapped’ by the Censor!

It appears to be up now; is it as you posted it? If so I just can’t see what is censor-worthy. By the way Civis Romanus sum exactly. Here’s hoping that wasn’t the bit “zapped”.

Yes!

The ‘flash to bang’ is frustrating.

Yes!

The ‘flash to bang’ is frustrating.

It appears to be up now; is it as you posted it? If so I just can’t see what is censor-worthy. By the way Civis Romanus sum exactly. Here’s hoping that wasn’t the bit “zapped”.

Civis Romanus sum, is the best example is it not?

You will be amused to hear that my reply to you, quoting Cicero, has been ‘zapped’ by the Censor!

The genetic make up of the people in these islands has changed more in the last 70 years than it has in the previous 6,000

…and that range of mixtures is what makes up the English ethnicity.

It’s curious that you have no problems referring to Scottish, French, Anglo-Saxon, Viking or Norman as ethnic groups, but apparently calling the English an ethnic group is too far.

I’ll never understand westerners that seem ashamed/unwilling to accept that they belong to an ethnic group. Apparently that’s a thing for “other people”.

Yes I think you have a very good point here. Rather have people from diverse origins who embrace English culture, than Woke people of Caucasian origin who are predominantly ashamed of it.

I suspect the vast majority of us whose ancestors were here in the mid 19th century are Celtic/Anglo Saxon in origin ( the mixture seems to me to be undeniable given the nature of the Anglo Saxon invasions ) and possibly pre Celtic also . Some Viking also but as the Normans were an imposed ruling class I doubt if many of us have much Norman ancestry. To me that looks like a specific identity much as the progressives deplore this.

Every other nation is given the courtesy of a national identity rooted in the land and the history of it’s people . Just look at the current love affair of the left with the Ukrainians. .

We English need that courtesy as well . Hard though it is for the progressive herd to countenance this.

Spot on, English is the land and culture to which you belong; it matters not what your ethnicity is, only where your loyalties lie. Like you I know that I have non-English genes (my mother was Scottish), but I was born and raised in England and it’s to England that I owe my loyalties (Britain is second in my loyalties)

The genetic make up of the people in these islands has changed more in the last 70 years than it has in the previous 6,000

Well Mr ‘Johan Schmidt’ I couldn’t disagree with you more … If you are born in England you are English like those before us from Scandanvia, France, Ireland and particularly Germany … it seems to me you have being consuming too much of your own rhetoric

Couldn’t disagree more! Of course we English are an ethnicity, compounded of all the things which make all ethnicities – common history, language, culture, and ancestry. Yes, ancestry – people whose ancestry lies in, say Somalia or Albania, do not become magically “English” just by being born in our homeland.

Can I ask, please. If you are ethnically caucasian, or african, but were born in China, would that make you Chinese?

Off course NOT,

Do black South Africans regard white South Africans as being fully, intrinsically ‘African’?

Why not?

Good question!

Good question!

Being born there is not indicative, but if you live there, are a citizen of China, and are loyal to China and it’s people, then yes, you are Chinese.

Indeed but the question wasn’t about nationality/citizenship but rather about ethnicity. so I am British and English. The latter is just a fact, whatever my passport says (and it says British). I can change my citizenship but not my ethnicity.

Just like a man with gender dysphoria can change his name but not his sex/gender.

There’s a massive difference to what happened throughout our history when different groups of mostly north European tribes who shared similar cultures and genetics came and settled in England and the UK. What’s happening now with millions coming from Africa and Asia etc with their vastly different cultures and beliefs is an entirely different ballgame.

There’s a massive difference to what happened throughout our history when different groups of mostly north European tribes who shared similar cultures and genetics came and settled in England and the UK. What’s happening now with millions coming from Africa and Asia etc with their vastly different cultures and beliefs is an entirely different ballgame.

Would other Chinese people agree? I suggest not. Are there many ethnically non-Chinese who are citizens of China? (I genuinely don’t know). What about Japan? Have you ever heard of or seen a ‘brown’ Japanese person (I apologise for the adjective – I’m not trying to be offensive, but really couldn’t think of an appropriate way to describe a non-Japanese-looking person.)

Going back to the difficult question of “Englishness” I would suggest that even if you live there, and are loyal to England you are in fact a British citizen : I think that the concept of “English citizen” is misguided. (Why not “citizen of Yorkshire” or “Cornish citizen”?) Unless, of course, you use the word ‘citizen’ with so broad a meaning as to be pointless. When does a tourist become a citizen?

True, you can only be a British citizen, just as Scots and Welsh are British citizens.

None of us are citizens. We are all subjects as we have an active monarchy. Or so I have been told on far too many occasions to count by my elders…

True, you can only be a British citizen, just as Scots and Welsh are British citizens.

None of us are citizens. We are all subjects as we have an active monarchy. Or so I have been told on far too many occasions to count by my elders…

Indeed but the question wasn’t about nationality/citizenship but rather about ethnicity. so I am British and English. The latter is just a fact, whatever my passport says (and it says British). I can change my citizenship but not my ethnicity.

Just like a man with gender dysphoria can change his name but not his sex/gender.

Would other Chinese people agree? I suggest not. Are there many ethnically non-Chinese who are citizens of China? (I genuinely don’t know). What about Japan? Have you ever heard of or seen a ‘brown’ Japanese person (I apologise for the adjective – I’m not trying to be offensive, but really couldn’t think of an appropriate way to describe a non-Japanese-looking person.)

Going back to the difficult question of “Englishness” I would suggest that even if you live there, and are loyal to England you are in fact a British citizen : I think that the concept of “English citizen” is misguided. (Why not “citizen of Yorkshire” or “Cornish citizen”?) Unless, of course, you use the word ‘citizen’ with so broad a meaning as to be pointless. When does a tourist become a citizen?

Off course NOT,

Do black South Africans regard white South Africans as being fully, intrinsically ‘African’?

Why not?

Being born there is not indicative, but if you live there, are a citizen of China, and are loyal to China and it’s people, then yes, you are Chinese.

Couldn’t disagree more! Of course we English are an ethnicity, compounded of all the things which make all ethnicities – common history, language, culture, and ancestry. Yes, ancestry – people whose ancestry lies in, say Somalia or Albania, do not become magically “English” just by being born in our homeland.

Can I ask, please. If you are ethnically caucasian, or african, but were born in China, would that make you Chinese?

There is no such thing as an English ethnic group. We are all a mixture. At a minimum I have Scottish & French ancestors (and probably Viking & Norman as well) along with Anglo-Saxon and possibly more. I am English (and not British) because that is my culture. Anyone else who shares that culture and attachment to England is welcome to call themselves English.

I think you have been influenced by Germanic twaddle.

Well Mr ‘Johan Schmidt’ I couldn’t disagree with you more … If you are born in England you are English like those before us from Scandanvia, France, Ireland and particularly Germany … it seems to me you have being consuming too much of your own rhetoric

Fine sentiment though we should classify ourself as British citizens in my view.

It is funny how ethnicty doesn’t matter, until suddenly it does.

And why I, in the World Cup, is GB the only nation to be able to put up 4 teams rather than just one. Is it not time to have team GB and a chance of winning rather than 4 teams that are also rans?

And why I, in the World Cup, is GB the only nation to be able to put up 4 teams rather than just one. Is it not time to have team GB and a chance of winning rather than 4 teams that are also rans?

What nonsense, being English is about being English, which is an ethnic group, not an idea, or a marker of having been born on a specific bit of soil.

You’ve been consuming too much american twaddle methinks.

Fine sentiment though we should classify ourself as British citizens in my view.

It is funny how ethnicty doesn’t matter, until suddenly it does.

To show our ethnic origins in a census is uneccessary … in England we are all English if born/live or have taken out citizenship … it’s a choice to be or not to be … England is about it’s people and not the colour of their skin.