Science does not operate independently from the realms of politics and culture. This was no more evident than with the coronavirus pandemic: questions of epidemiological modelling, the efficacy of lockdowns, vaccine mandates and social distancing all saw the world split into different camps. And whatever position one took on lockdowns, for example, became convenient shorthand for their politics writ-large.

The emerging question of continuing excess deaths in the aftermath of Covid has not escaped this phenomenon. It may turn out to be as polarising as any other Covid-19 controversy. Over the past three months the number of excess deaths in the United Kingdom – that is the amount of people actually dying compared to the amount of people expected to die – has been consistently trending upwards. And over the past ten weeks deaths have been in excess by 15%.

The contours of the debate are becoming clear. On one hand, there are those insistent that the deaths are linked, in some way, to the Covid vaccines. On the other hand, establishment voices reject that theory wholesale, and instead suggest the excess is tied to the lasting impacts of Covid infections, illnesses that went undiagnosed thanks to lockdown, and a myriad of other complicating factors.

Stuart McDonald, head of Demographic Assumptions and Methodology at Lloyds Banking Group, sees this split as an unfortunate by-product of the pandemic more generally: people are jumping to assumptions to satisfy their preconceived ideas about the world before fully interrogating the data. What we know for certain is that more people are dying than we would expect: “It’s an undeniable fact.”

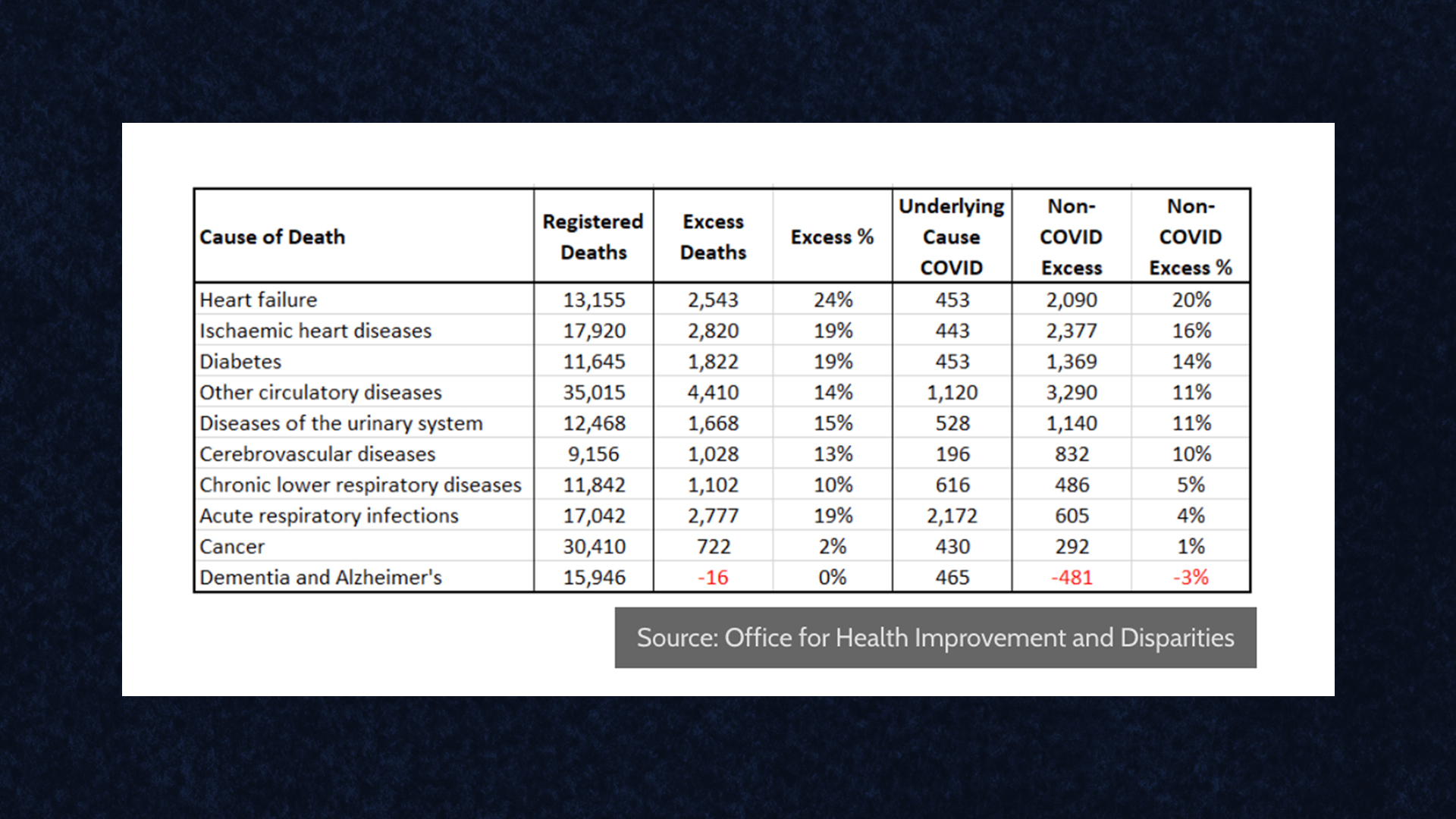

Working out why is a much harder task. On inspection of the data, however, it is clear that some of these deaths are disproportionately attached to certain health conditions: “The majority of the cases are cardiovascular, circulatory, cerebrovascular.”

But death certificates, McDonald explains, often list several causes. And those causes can be hard to disentangle from one another. The above table shows there are 13,155 deaths in some way linked to heart failure, and “only a very small proportion of those had Covid as the underlying cause.” But, “if we look at the chronic lower respiratory diseases, or the acute respiratory infections, the majority of excess deaths we’re seeing in those two cases may actually be attributable to Covid.”

Those wary of the longer-term side effects of the vaccine may take energy from this table. If we have a strong indication that cardiovascular deaths are particularly elevated, and we know that officially accepted side effects of the mRNA vaccines are myocarditis and pericarditis, might these things be connected?

McDonald is unconvinced. Post-viral cardiovascular issues are well-known and well studied consequences of other viruses. “We have historic evidence of elevated cardiovascular risks extending beyond the immediate acute infection, and we have pretty firm evidence that there are a sub-group of people who have had Covid-19 that will experience elevated cardiovascular risks” he explains.

Overall, to further challenge the arguments of the vaccine sceptics, “the data consistently shows that the fully vaccinated have a lower mortality rate than those that are unvaccinated.”

“The vaccine could simultaneously be reducing the risk of the vast majority and also be putting a small number – a very small number – at elevated risk. This is why vaccine trials take place. And this is why the vaccine has been very carefully monitored since its rollout. And indeed, there have been changes to recommendations made about which vaccines we give to certain age groups based on the reports of those rare side effects.”

We cannot 100% rule out any impact of the vaccine on these excess death figures. But “there are so many stronger hypotheses than that one,” McDonald argues.

Among these is the acute pressure currently suffocating the NHS. The target ambulance response time, for example, is 18 minutes. In July the average wait time is 59 minutes. When it comes to strokes and heart attacks, fast action is the most effective treatment. And so, “if it takes nearly an hour to get an ambulance to these people, then sadly, there will be more deaths.”

It is not just the current state of ambulance response times, however. The lockdown itself caused significant behavioural changes in people who would otherwise have sought medical attention.

“While lockdowns didn’t prevent people from seeking care legally, there was a behaviour change. People were not accessing treatment at hospitals to avoid a perceived risk of contracting Covid. And that’s had knock on effects: with elective non urgent care waiting lists have grown, up more than 50% since before the pandemic. Now around 6.7 million people are on those lists.”

This is playing out in the statistics as well. “We expect a certain number of people to come forward with medical concerns every year – lumps, other things that usually cause worry. Those numbers fell, and they fell substantially, particularly during the first lockdown.”

One of the biggest concerns during lockdown – particularly among those more sceptical of the project – was that it would cause delayed cancer diagnoses, and ultimately a big spike in cancer deaths. That is not currently observable in the data. But McDonald is keen to stress that the fears about cancer deaths were legitimate.

Both the disruption the health service experienced as a direct impact of Covid, and also the actions we took to mitigate the spread of Covid, affected the number of cancer diagnoses doctors were able to make. “This will mean a worse prognosis and shorter life expectancies for cancer patients who ought to have been diagnosed a year or two ago” McDonald argues. But that is likely to play out over a much longer time period. Cancer delays are not playing a material part in the current excess, but it is uncontroversial to suggest that they will come.

A consensus has yet to emerge on the causes behind the UK’s troubling death figures. And this makes the whole topic fertile ground for the culture warriors. It seems clear that hospital delays are a significant – if not the most – significant factor. But we are still in the early days of analysing this phenomenon, and far from any kind of certainty.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribethere were so many things not explained fully in this discussion. McDonald clearly has a belief that the vaccines have saved lives – he offers no real evidence. World data shows that highly vaccinated countries have fared no better than those not highly vaccinated.

For example the age groups of those dying in the excess group are primarily those in the working age group – MCDonald did not show these figures – these are not typical of people who have heart problems

The discussion of who is counted as vaccinated – those in the 2 weeks following a covid vaccine for example being included in the unvaccinated group – so if death occurs then you will be counted as unvaccinated.

His statement that the vaccines have been fully trialled is completely wrong. Long term vaccine trials normally last years before they are used – this has not happened.

He makes no mention of the approx 2500 people who have died directly due to the vaccine. These people have coroner reports saying so and their families are slowly being given money (watch Mark Steyn on GB news). However these inconvenient deaths are taken down by social media.

Read conservative woman / daily sceptic to find further info produced by real doctors with charts data and detailed analysis from those who had their voices silenced by big tech over the past two years..

So I found with a couple of minutes searching that :

https://actuary.eu/how-did-downing-street-pick-up-to-covid-messages-from-uk-actuaries-in-the-media-tea/

STUART MCDONALD is Head of Demographic Assumptions and Methodology for Lloyds Banking Group.

and:

https://www.lloydsbankinggroup.com/media/press-releases/2020/lloyds-banking-group/lloyds-banking-group-and-microsoft-form-partnership-to-accelerate-banks-digital-transformation-strategy.html

Lloyds Banking Group (LBG) today announced a strategic partnership with Microsoft focused on accelerating the Group’s digital transformation.

Freddie you need to really do some further digging on excess deaths.

There certainly has been a lot of censorship of people posting on social media about the possible harms of the vaccine, and that’s unfortunate. But that doesn’t mean that those censored are correct.

Those claiming that vaccines is responsible for any but a tiny sliver of the excess deaths have failed to show any evidence to support that claim. Until they do, or other data comes to light, that claim cannot be taken seriously.

Is having this WEF Corporate man defend the vax that much different to if Freddy did not try to give the Agenda guys some cover – and had a Pfizer exec tell us how these numbers mean nothing, and move along…..

The problem is that data will only come to light with research, and medical studies like this costs enormous sums and who is going to pay the bill? Not the pharmaceutical companies that normally sponsor medical studies and not governments that would be liable for any adverse findings. Like all research you start with an idea you wish to prove – nobody with the means to pay for it wants to prove that there are any issues with the vaccines.

The following link presents an investigation of 23 million people in the Nordic countries: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamacardiology/fullarticle/2791253. They assessed the risk of Myocarditis within 28 days, thus not discounting the first 2 weeks following vaccination. There was a small risk (4-7 excess events 100.000 individuals). Most vaccine induced Mycoarditis cases are not severe and it is thus extremely unlikely that any significant number of deaths followed the vaccine. Do note that Denmark was the first country to shut down the use of the Astra Zeneca vaccine due to the identification of two deaths due to this particular vaccine – the country has thus not tried to hide all vaccine deaths.

Furthermore, vaccine trials are usually long due to the interest in capturing the long term effects, not because of safety concerns. That cut-off is usually 6 months, as described in this well written overview: https://bostonreview.net/articles/the-long-term-safety-argument-over-covid-19-vaccines/

Thus, I understand the concerns and scepticism, but since Denmark has used far more mRNA vaccines (relatively speaking compared to the UK) and we don’t see these excess deaths, it just seems very unlikely that mRNA vaccines lead to the excess deaths in question. Rather, the ambulance / hospital waiting times appear horrific (as an outsider) and a much more likely culprit.

I wonder if the upheaval and anxiety of always moving patients with (possible) heart attacks to hospital should be investigated. Perhaps care at home with attendance of carers and necessary equipment (oxygen?) could be a better procedure and could save lives.

Just a thought!

I wrote a long post that somehow didn’t post. Short version – I don’t believe any member of the ‘establishment’ on this issue. They have denied, censored and deflected any criticism of the Narrative regarding the vaccines. Like myocarditis – which was originally denied, censored and minimized – these deaths will likely turn out to be caused by the vaccine. That is why in the US they are trying to call it Trumps vaccine – and everywhere they are now claiming that ‘no one forced you to take the vaccine.’ They know the information about vaccine injuries is just going to get worse and worse.

The clear majority of old Danish people (+95%) have received a mRNA vaccine. Why haven’t we seen the same excess deaths in Denmark – compared to countries that have vaccinated far fewer old people with mRNA vaccines? (US, UK etc.).

Furthermore, in Denmark we automatically register the diagnosis a patient receives. We can thus easily link the diagnoses that a vaccinated patient will receive in the future (compared to those not vaccinated). The numbers in Denmark do – not at all – support your position. Do you have any explanation for that? I guess, in principle, doctors could be deliberately misdiagnosing. Is that the hypothesis, that 10.000s of Danish doctors engage in such a practice?

There will always be a few exceptions to even the most accurate trend. Instead of cherry-picking, why not address the big picture regarding mRNA vaccines- particularly in context of the unfavorable gold-standard RCT mortality results, most notably the 45% increase in cardiovascular mortality relative to placebo?

This is great. Firstly, thanks once again to Freddie for being willing to politely and civilly host the debates that other media outlets won’t touch. And not just host them but ensure they are actual debates! Unherd is truly one of the highlights of the past few years and shows what the media can be, even to people otherwise cynical about it. The subscription is constantly worth it.

Secondly, thanks to Stuart McDonald for agreeing to take part and intelligently debate such a hot-wire topic. It isn’t easy, us commenters BTL can be harsh, but it’s really appreciated too.

The YouTube comments (>500 vs 3 here, wow) seem pretty much on the vaxx-cause side and saying that Stuart gets flustered later. I don’t see how you couldn’t get a bit flustered being put under intellectual pressure by Freddie, talking to the press and on video. I pretty much am on the side that it’s caused by the vaccines simply because – as Stuart says – this pattern is seen in many countries and across Europe and the causes are known to be triggered by the vaccines, whilst NHS collapse is a UK specific problem. Also there’s the drop of births in many countries, combined with the fact that my girlfriend has so many friends and acquaintances who had menstrual disruption. So you don’t have to really work hard to convince me that something has gone badly wrong here especially for the young.

Nonetheless Stuart makes many good points and argues his corner respectably. The timing issues are real. The excess deaths should have started immediately but more or less everywhere you see this spring increase. What changed in the spring? And it seems unquestionable that a whole lot of cancer etc diagnoses went AWOL – it seems hard to imagine that had no impact, so even the most generous vaxx-cause position must still accept that some of the excess deaths come from delayed diagnosis and treatment.

Despite that I don’t quite understand his confidence about vaccines. How can he be firmly convinced that there’s “nothing in the data” saying that vaccines can’t explain this, or that this is an “irrational theory”, when there’s entire databases filling up with case reports about people who were injured or even killed within days of taking the shots?

I’m not really sure you can find anyone without an axe to grind on these issues. Vaccine fanaticism is so extreme, so rabid and so vicious that anyone who speaks out about this under their own name let alone whilst associated with a major bank is going to immediately be cancelled. Would Lloyds have even let him go on Unherd at all if he wasn’t going to take the party line? It seems unimaginable. Look at what happened to the HSBC banker who spoke out about climate related hysteria – making an actuarial argument no less – and I find it very hard to imagine Mr McDonald’s hands were truly untied.

Perversely, I therefore find myself trusting pseudonymous people the most, simply because they can speak without fear of their personal lives being wrecked by the large number of people in high up positions with quite plainly ideological commitments to the COVID vaccine programme. After all, how many people who can influence whether Mr McDonald has a job directly or indirectly encouraged/forced people to take the shots? Very few have clean hands on this issue.

Thanks for a constructive contribution. Just a couple of quibbles (we are never going to agree on the major point anyway):

Well, I find both of these points are unconvincing for the following reasons.

Re: ideology.

Obviously this one can’t really be debated via reference to datasets, but my experience is the opposite. I’m sure you think I’m now an “anti-vaxxer” and frankly I’m tempted to become one because it seems like the rational position, but before COVID I never thought about vaccines and had bog standard positions on them. Ditto for all the people I know who didn’t take their shots either. No pre-existing views on the matter, and a range of politics.

Moreover, the “COVID vaccines are causing excess death” argument is clearly not ideological. Ideological arguments tend to reduce to unverifiable assertions about human nature, e.g. the idea that communism could have worked if the USSR had done things differently, or that private sector industry is superior to state run industry, are ideological beliefs because the arguments rest on axiomatic assumptions about how people work or really are.

The cases both for and against the COVID vaccines are arguments driven by tight claims about hard data. The belief that there’s ideology at work on the pro-vaccine side comes not from the nature of the arguments themselves, but the fact that claims about the data by the public health and pro-vaccine people keep turning out to be slippery, distorted, hidden, corrupted in various ways etc. Therefore whilst their arguments are not directly ideological and look scientific, a lot of the behavior we’re seeing to support those arguments looks suspiciously like motivated reasoning. And why would anyone do that, even if they don’t e.g. own pharma shares? Well, public health is a form of progressivist collectivism.

Re: databases.

But more generally, The argument that the reports should be ignored because of the potential for false reports seems irrational. Why even bother collecting case reports at all if even literally flagging the fact that they exist is blown off by saying “oh well of course people file reports, that doesn’t mean anything”. This appears to be an argument to shut these surveillance systems down entirely and thus just ignore anyone who says they were injured. When phrased like that, it sounds a lot less scientific, doesn’t it? Especially because all major regions collect case reports of vaccine injuries. Vaccines can hurt people and this has happened before, it’s not in dispute or a controversial claim. The existence of these systems was considered an important argument for why vaccines are safe before 2021 – now we find people arguing that this supposed safety system doesn’t mean anything and should be ignored!

Re: Ideology:

Funny enough, from where I stand it looks like it is the arguments from the antivax side that turn out to be “slippery, distorted, hidden, corrupted in various ways etc.” and that look “suspiciously like motivated reasoning“. This is maybe not so surprising. When you are strongly convinced about one position you tend to be also very convinced by arguments in favour, and dismissive of arguments to the contrary. People who then argue with questionable arguments for obviously wrong conclusions do tend to look like they had some kind of ulterior motive. That goes for both sides of course. The question is how you got so strongly convinced about one side in the first place, and how both sides can get out of the hole.

As for the databases, your objections show that you did not understand my argument (maybe I made it badly). The problem is not whether the database is complete, or whether the reports are false. If someone says he got a heart attack two days after his COVID vaccination I am pretty sure that he did so. The problem is whether the heart attack was *caused* by the vaccination, or whether this was just a coincidence. After all, lots of people get heart attacks, and lots of people got vaccinated, so you would expect a lot of coincidences. Before you can conclude anything, you need to check the reported adverse effects against what you would expect to happen by chance (which is why a small number of a rare effect is good evidence of a problem with the vaccine, whereas a large number of a common effect is not). That is the way these databases are used by professionals, and the way they are intended to be used. And if people are not at least considering this factor, I think their arguments do not stand up.

The question of the MMR vaccine and autism is a good illustration. I am sure that quite a few parents watched their children get diagnosed with autism not long after they got their MMR vaccine, and are convinced that the vaccine caused the problem. I am equally sure that this is a coincidence, caused by the fact that everybody get the MMR vaccine at about the age where autism starts showing up a a problem. Whether that is true or not, it would certainly take a *lot* more than looking at raw numbers and horrible anecdotes to prove a connection.

Re: ideology. I think the problems with the arguments differ between the two sides.

On one side you have governments and “the establishment”. They have all the power here, and in particular, they have the unique power to collect and distribute data. What they make available is what we get and there are no obligations on them. They also have a very strong policy desire that everyone takes their vaccines. Naturally there is the temptation to manipulate or suppress data to bring about their intended outcome. This can and has led to corruption and slipperiness of all kinds. The space is awash with tricks that are hard to explain as merely being domain-specific weirdness or incompetence e.g. the constant stream of discoveries that cohorts described as “unvaccinated” are actually defined so as to include vaccinated people. This sort of thing should not be tolerated and looks strongly like ideological corruption.

On the anti-(COVID)-vaxx side, the problems are very different. Let’s say that this is a mix of people who made up their mind before COVID, and a mix of people who just wanted to know whether vaccines were in fact OK or whether there were problems and who had realized that their governments were not exactly neutral parties. My sense is that the first subgroup doesn’t produce much or any analysis. If they did, they’d certainly make reference occasionally to pre-COVID writings against vaccines but I never see this. All the writers I follow who analyze this stuff seem to be newly created by COVID.

At any rate, regardless of which camp they’re in, this group is completely constrained by the availability of data produced by governments. A lot of their effort goes into trying to sift “truth” out of datasets that don’t want to be tortured in those ways. Inevitably, this leads to arguments that are sometimes weak, or can be attacked in various ways – the source material is of low quality and people do with it what they can. However this latter problem is not caused by or related to ideology, in my view. When I read analysis that paints COVID vaccines in a bad light, I don’t see much evidence of deliberate game playing or distortion. The definitions they use are normal, the way they work with data is sound, the confidence in the conclusions (or lack of it) is normally made clear. Of course I’m just stating my opinions of these analyses and it’s entirely possible we’ve been exposed to totally different material, and thus have different views because of that. But this is what I’ve seen.

The database issue is a good illustration of this. The argument against is basically that they’re false reports where I’m using “false” to include “believed to be causal but isn’t” and therefore the numbers can’t be used without knowing the background rates of all these things. So, of course, it goes without saying that the governments that run these databases know those rates, have measured the URFs, multiplied them through and done the ratio calculation …. right?

Right?

Wrong. Of course they haven’t. At the start of the rollout the US CDC said they’d monitor VAERS for safety signals. Reports went vertical, yet they say there’s no safety signal … OK fine, some so-called “anti vaxxers” said, let’s FOIA them to find their underlying calculations so we can see why they’re saying there’s no signal. The result was not a carefully worked spreadsheet showing that the report level matched the background rates and were mostly just coincidences. Instead the result was a letter saying the CDC has never done any analysis of VAERS whatsoever and doesn’t think it’s even their job at all, even though they previously specifically said they’d do so.

https://jackanapes.substack.com/p/new-foia-release-shows-cdc-lied-about

So clearly, the idea that this is a safety system is for the birds. They aren’t even looking. A bunch of Substackers have tried to do these calculations themselves by using pre-COVID background rates and URFs reported in the literature and found that the numbers are sky high, way higher than you’d expect if this is just coincidences but, of course, this sort of analysis is the very type you are writing off as ideological or non-expert!

Calling these ‘false’ reports is misleading, whatever your definition. The problem is not with the reports. The problem is that analysing them to get meaningful conclusions out is actually quite difficult. Which I assume is why for instance the CDC does not have a complete spreadsheet that tells you everything you might want to know.

There are what I would call some *very* reliable data out there. People who have analysed the medical and vaccination records for tens of millions of people and published the results. Carsten B references one, above, there was another one based on UK population data etc. Of course these are done by professionals, with access – and known competence. I look at those, check for what seems calm and well-supported objections, and conclude that whatever vaccine adverse effects you get, they are not huge. Admittedly, I also start from the assumption that the total health system of the world has a general desire to keep people healthy, and that egregiously unsafe practices would eventually get signalled. That may or may not be problematic, but it does mean that I have available a fairly large amount of professionally calculated and evaluated data to make use of.

If, on the other hand you assume that anyone with full data access is likely to be deliberately lying in order to cause avoidable sickness and death to hundreds of thousands of people, the picture changes. At that point scientific consensus and all well-conducted investigations are by definition suspect and can be discounted. The only people you can trust are those who are convinced that governments are most likely lying, and who have neither the skill, the knowledge, or the data access to produce reliable results. And who, quite frankly, are too biased to make a neutral analysis even if they got the data access.

Disagreements are not new to science, but ultimately the weight of evidence prevails, and there is a consensus on what is going on. That does, however, require some agreement on how data should be analysed, which seems to be missing here. Let me end by pointing out that if the analyses of Jackanapes are no good, claiming that the CDC has not done their bit does not make them any better. I am willing to listen to evidence, but unless you can produce some reliable analysis in non-apocalyptic prose to support your point, I am not going to move my opinions.

One of the problems with relying on self-reported side-effects of drugs is that we know control groups in drug trials who have only been given placebos also report high rates of side-effects – just as some people seem to be miraculously “cured” by placebos, despite them having no medicinal value.

For the vaccine trials that can be because the placebo wasn’t inert (it was another vaccine).

Physician, heal thyself eh? Don’t underestimate the power of placebo! The variation of sude effects from one individual yo the next is also huge! Medication is hit and miss, quite literally. However, looked at statistically the beneficial effect is generally quite convincing.. not much consolidation if you’re the 1 in 10 or 1 in 100 though.

“A new CDC study provides strong evidence that mRNA COVID-19 vaccines are highly effective in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infections in real-world conditions among health care personnel, first responders, and other essential workers. These groups are more likely than the general population to be exposed to the virus because of their occupations.”

This is the paper Walensky put in front of the FDA in the USA to get “Comirnaty” approved. This isn’t “slippery”. It is criminal fraud and racketeering and should be prosecuted. They have tried to memory hole this crap but you can still find the truth. It says prevents. It doesn’t say reduce severity.

https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/p0329-COVID-19-Vaccines.html

..vaxx fanaticism..? I’m not sure I saw any evidence of any kind to support that assertion? Can you give examples? An official requirement for a vaxx is hardly “fanaticism ” is it? Authoritarian maybe, but fanaticism???

Actually I agree with you. But Norman Powers was claiming that pro-vaccine fanaticism was dominating the debate, and I wanted to 1) stay in a non-confrontational mode, 2) make the point that fanaticism was at least as strong on the anti-vaxx side. Which I notice Norman Powers did not accept. To him the pro-vaccine people are fanatics, whereas the antivaxxers are simply calm rational people trying to find the truth in a world where every single member of the establishment is lying. Personally I think the etablishment is honestly trying, whereas the anti-vaxxers are driven by motivated reasoning and preconceived notions – at best. But I cannot deny that apart from the fact that the data (and the people who know how to analyse them) are on my side and not on his, there is at least some symmetry in those positions.

Conversely, these are also the people whose claims are impossible to verify, and are generally free to make up whatever stories they like to support their position.

That’s literally the exact opposite of what they do in my experience. I’m talking about the sort of people writing on substack, daily sceptic etc. They’re (sometimes) pseudonymous, or at least not famous / institutionally affiliated, so they can’t just make up claims and say “trust me I’m an expert”. That’s what governments do! Instead they have to write long complicated analyses where they are constantly referring to source data, explaining their working and how they arrived at their conclusions, etc.

It’s for that reason that their conclusions are so much more trustworthy than what governments and media produce. You can check their claims and I often have. I can only think of a handful of times in the past few years they failed fact checks, and those times were all when they did dumb and unusual stuff, like highlight viral tweets that later got debunked. The data analysis is at least not worse, and often better, than what governments themselves do.

My advice: don’t never trust nobody unless ye have to! Then go with yer gut feeling: probably, statistically as good as any! Like you say, too many careers rise and fall on what is said: truth and accuracy take second place, at best.

…”the excess deaths should have started immediately…” really? Why? I’m mot disputing what you say: merely asking the question.

Yes, what if the vaccine causes mild heart damage, which if left untreated causes serious problems months later?

What happens if mild myocarditis goes unnoticed and untreated?

Are you not ignoring the most plausible explanation for most of the excess deaths by focussing only on ambulance delays as an indicator of NHS “pressure” (better read as dysfunction as isn’t primarily about extra volume or extra sickness)?

John Burn-Murdoch of the FT did a thorough analysis of the estimated extra deaths caused by long A&E waits here: https://twitter.com/jburnmurdoch/status/1562004612172873728?s=20&t=QbH3OaRxBP6cnozb-UIPQg which is based on a large volume of patient-level data exploring the relationship between waits and mortality.

That analysis produces an estimate that explains at least half or more of the age-adjusted excess death numbers. Extra deaths caused by ambulance waits pre-A&E would add to that total.

While there might not yet be a consensus, this explanation looks to be fairly solidly founded.

(COI I’m a co-author of the EMJ paper that demonstrated the link between A&E waiting times and mortality).

This is interesting but isn’t it rather UK specific? Did you study other countries simultaneously e.g. look at Spain, very high excess starting in the spring but their health system is not (as far as I know?) in a state of collapse comparable to the UK.

And Switzerland apparently

https://www.eugyppius.com/p/sustained-as-yet-unheard-of-excess

But is it possible that an increase in mortality (from some third factor) causes an increased in demand for ambulance services which shows itself as increased A&E waiting time?

Kudos to Unherd for attempting to analyze this question objectively. Without getting into the question of whether the covid vaccines are at least partly responsible for excess deaths, I’m certainly willing to believe lockdowns are a significant part of the problem because they deterred people from seeking timely medical care.

I must admit I wonder why Lloyd’s Banking Group allowed one of their senior statisticians to discuss this hot topic on Unherd. What’s in it for them? They must know that Mr. McDonald will alienate somebody no matter what he says.

I hope that Freddie will return to this issue in a few weeks time. Then he may have more data and can better press those who reassure us “nothing to see here” about any possible link between vaccination and non covid excess deaths. There have been more than 10,000 of these deaths (above that which is expected) this summer in England and Wales. Of course, they may be right, and those who think there might be a link may be completely wrong.

But I think the following facts are generally accepted:

Hearing what others think about these claims would be interesting.

The interview puts it pretty well. Clearly, analysing excess deaths is extremely complicated (which takes care of 7). 6) just means that in a few specific cases the authorities have accepted that vaccination caused damage (or that it would be bad PR to say no) and does not reflect on the general situation.

The rest is just a scenario. You can make a plausible story and if you already believe it is highly likely that vaccination causes a lot of deaths, your story serves as corroboration to what you already believe. Nothing necessarily unusual here – even in particle physics experiments that confirm the current theories are accepted much more easily than those that prove them wrong. The question is why you believe in the harmfulness of vaccines in the first place? If you start from a neutral stance, what evidence would make you conclude that COVID vaccines are so dangerous? The big studies (tens of millions of people) did not find any evidence that vaccines were dangerous. The adverse effects databases always have a lot of events to report, and it takes careful, skilled analysis (and probably additional work) to draw conclusions from them. Vaccination has been around for over 100 years, and has mostly not caused these problems. As for population-level statistics, how do you distinguish between damage from vaccination, damage from people catching COVID, and damage from disrupting the health care system, and keeping people indoors?

Personally I would say that we should assume that the vaccines are (mostly) safe as our health system says they are, unless there is some strong evidence that they cause all these deaths. And where do you see the strong evidence? Or would you stop vaccinating on a hunch without it?

Thanks for your interesting post. No, I don’t think we should stop offering vaccination to those who want it. But I do think that pressure to take vaccines should end and the censorship surrounding this issue should stop.

I only really took a second shot so that I could travel abroad, but the injection didn’t substantially reduce my risk to others. Or do you disagree?

It would help if you could offer a link to: ” The big studies (tens of millions of people) did not find any evidence that vaccines were dangerous.”

I agree vaccination has mostly not caused these problems in the past. But mRNA vaccines are new products and work in a different way from past inoculations.

Usually, new vaccinations have to be shown to have a +ve risk-benefit. It’s best if those selling them show that, on balance, they reduce mortality in controlled trials. This was never done in this case. And now we have significant numbers of “excess deaths”. It’s a worry.

I can come up with these three:

Admittedly I have not analysed them in detail – I rely on their conclusions, peer review, and the judgement of better informed debaters, (like Elaine Gladys-Lieper). But they are there to analyse for weaknesses, if you are so inclined.

Vaccination does not *prevent* you from either catching the disease or passing it on. Regrettably. The natural assumption would be, though, that a less severe disease would cause less contagion to others. To my mind the burden of proof is on those who claim that vaccination has no effect whatsoever on transmission.

Vaccinations have generally been tested at great length with detailed comparisons against what happens to the non-vaccinated. But then the situation has always been that of a well established disease with well known damage profile and a stable existing situation. Getting that kind of data for COVID would surely have required waiting for a few years while you established the baseline damage of the disease and checked for long-term vaccine effects. Meanwhile we should all have caught COVID, unvaccinated, with quite serious effects overall. To my mind rather like letting the house burn down while you did a thorough check of potential water damage that might arise from trying to put the fire out.

Well, I didn’t expect such a well-researched and wide-ranging response. Thank you for taking such trouble and time. I would make these observations.

In the first paper, Karlstand et al followed up 23 million people in 4 Nordic countries for up to 9 months (December 27, 2020, to October 5, 2021) who had received the first and second doses of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. They found a very small increased risk of a rare, potentially severe condition (myocarditis).

In the second study, Petone et al studied almost 40 million adults (who had received at least one dose of the vaccine over a similar period of time) for a month after the injection. They also found a very minimal increased risk of a similar disorder.

In the third study, Barda et al studied almost 1.8 million people (who had been vaccinated over four months) for 42 days. Similarly, they found a minimal increase in the risk of the same condition.

I would point out to you the very short follow-up periods of these studies. The worry is that vaccination may exacerbate inflammation in the cardiovascular system in the medium term (over months or even years), increasing the risk of thrombosis and so heart attacks and strokes.

Usually, when a new medicine is introduced, it is up to those selling the product to show it is safe. Here you ask that others prove vaccination represents an unacceptable risk. I find this reversal of “the burden of proof” unsettling.

I agree that there is very little evidence that vaccination “prevents” you from either catching the disease or passing it on. I’m afraid I again have to disagree that it is up to others to prove that vaccination fails to work. It is up to the makers to prove it does work.

I agree that “Vaccinations have generally been tested at great length with detailed comparisons against what happens to the non-vaccinated”, and there was no time to undertake such studies in this case. But now that the emergency appears to be ending, we have the opportunity to undertake these studies. We need to try to understand the unexplained rise in excess deaths.

Thanks for your answer. You are certainly right that the follow-up periods have been fairly limited. Just as an aside, could we agree to conclude that, following these papers, COVID vaccinations are safe, as far as side effects for, say, the first six months are concerned? That would be a rare case of agreement across the divide.

On whether vaccination works, my understanding is that it is clearly established that vaccinations work very well to prevent hospitalisation and the more serious effects of COVID. Do you agree or disagree on this point? It does not *prevent* reinfection, or transmission, and I think we both agree that it is not known to what extent it reduces them. Also I guess it is common ground that the protection given by vaccination decays over time, somewhat more rapidly than one would like

For longer term effects you are quite right that we do not know. Given the short time that has passed since vaccinations started, and the very wide vaccination coverage that makes it hard to find a control group, the first six months or so are arguably about the best we can check for the moment. But then it is not only vaccinations where we do not know the long term effects. We also do not know the long-term effects of COVID, hence all the worry about long COVID, which might *also* be the cause of the excess deaths. Vaccination might have unpleasant long term effects, but is equally possible (and equally unproven) that vaccination might *protect* against long COVID, and so provide *better* long term prospects. We just do not know for sure.

I’d say that the remaining question is how to deal with the long-term risk considering that we do not yet know either the cost or the benefit for sure. Clearly no one would have rolled out these vaccines at such speed against a more established disease, because the risk would have been too high. But a lot of that risk has already been avoided by now: There is a proven benefit, and short-term ill effects have been checked much better than you would normally do: I doubt that most vaccines would gather 40-50 million tested individuals before being rolled out. I also doubt that most vaccines get a 5-10 year follow up to check for long term effects before being used in anger. So, I wonder why you find it necessary to apply so stringent precautions for a vaccine that is already ‘odds-on’, as it were.

Whether a vaccine mandate makes sense does depend on how much vaccination does to reduce transmission. I am less impressed by your right to remain unvaccinated if it translates into your right to put my health at risk, but we would need some actual data here, rather than just worries. But as for ‘censorship’, I do think that, problematic or not, anybody trying to scare the population away from following public health guidelines should be held to at least some minimum standard of evidence.

Could I take your last point first? People who have tried to have a sensible, rational discussion about this issue on social media have been censored. John Campbell’s YouTube channel is a good example. The problem is that it raises the possibility in some people’s minds that something is amiss here. In my opinion, it is counterproductive and very unfortunate. I’m surprised you continue to support it.

Most of my friends, acquaintances and family were vaccinated, but the majority suffered from clinical covid. If the purpose of the vaccination program was to prevent the spread of disease in the community, it clearly failed.

I agree the evidence is clear that the vaccination prevents hospital admission and death. But this is only in the short term. After all, if this weren’t true, we wouldn’t need boosters.

These short-term benefits of vaccination clearly outweigh the short-term risks for most people. This may not be true for the under 25 yr old. I don’t know the figures and would love to see them.

As you say, we don’t know the medium and long-term risks of vaccination. The recent increase in sudden death from cardiovascular disease may be due to long COVID or the unintended consequences of NPIs on the health service, the vaccination or some other cause. We don’t know. But it must be due to something.

I bring to your attention the range of articles on many of these issues published in “The Daily Sceptic” (which isn’t being censored).

Now look here Unherd staff, one should write the “number of people” and not “the amount of people”.

Carry on that man!

At long last the vaccine kicks in,

“Death where is thy sting”?”

The data are obfuscated and cannot be relied upon. Why not seek direct evidence by autopsy?

https://doctors4covidethics.org/vascular-and-organ-damage-induced-by-mrna-vaccines-irrefutable-proof-of-causality/

OK, we get a possible mechanism, and pathology on a few patients. But before believing that vaccines are damaging huge number of patients, I would like to see some evidence of, well, huge numbers of patients being damaged. Which seems to be lacking so far. Other, better informed people can judge the medical and scientific vaidity of this. As for myself, I would never trust any paper containing the following sentence: “Overall, these vaccines can no longer be considered experimental—the “experiment” has resulted in the disaster that many medical doctors and scientists predicted from the outset“, which is clear proof of anti-vaccine bias.

Many doctors and scientists DID predict this, but were silenced peremptorily by powerful forces. mRNA IS experimental and the panic ensured it benefited from vastly shortened clinical trials. The latest booster was approved by the FDA based upon tests performed on 8 mice. This isn’t anti-vaccine bias, this is acknowledging risk.

My original point stands: do more autopsies. Obfuscated stats won’t help in this regard.

The belief the symptoms of having the vaccine in 2021 are not expected now after one year misses the crucial aspect of many boosters people got and the cumulative consequences on the heart and immune system

Yes, or what if it takes a while for the mild heart issues to get serious if untreated.

Very helpful and interesting discussion. Nice to see two people who have strongly held but differing views discuss an issue with depth but also uncertainty. Rants tire me out. This kind of discussion makes me think.

Stuart McDonald was a good guest to hear from. He’s an expert in statistics, and that’s what’s needed here. I’m not sure if he does much with causal inference, but I suspect he does. Few people discussing this issue seem to. They should.

I’ve studied causal inference for many years now, and it’s an interesting topic. Judea Pearl won a Turing Award for his work on the subject (though he’s probably better known to the public as the father of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl, beheaded by Pakistan terrorists in 2002).

Richard Doll and AB Hill developed the first principles of causal inference way back in the 1950s and 60s when they studied the causal link between smoking and lung cancer. They debated in print the father of statistics Ronald Fisher, who claimed that a link could not be proven. He was wrong.

I agree with Stuart McDonald. Applying the principles of causal inference, I’ve seen solid evidence that the vaccines has saved lives. I’ve seen no solid evidence that they kill any more than very rarely. The excess deaths seen in the UK and other countries seem much more likely to be from other causes.

Can I convincingly explain why in a comment here or in a thread on Twitter? No. And someone who doesn’t know causal inference wouldn’t be convinced anyway. You need some grounding to be able to debate the issue properly, and the issue is complex.

Not that I blame those who believe that the vaccines may have something to do with excess deaths. It’s certainly possible. That should be looked into. Though good data is hard to get, more data is needed.

I do blame those like Alex Berenson, Naomi Wolf and Robert Malone who suggest that they have data that shows that mRNA vaccines cause at least some excess deaths. They don’t have that kind of data, and they shouldn’t be making such extraordinary claims without extraordinary data. This is too important an issue to mislead on.

The problem with this argument is that during COVID we saw incontrovertible evidence that epidemiology is an extremely unreliable field, in which claims are routinely made with high confidence yet turn out to be wrong. The field seems to learn nothing from these events. Instead they keep on churning out models that make causal claims which not only turn out to be incorrect post-facto, but which had already been invalidated before the models were published at all.

In contrast, my impression of statistics as a field is relatively good. You’ve got the whole objective vs subjective Bayesian debate which is a bit of a mess, but they seem to pretty much play it straight.

So when you present an argument between a famous statistician who disagrees with a bunch of epidemiologists, the obvious inference is that the epidemiologists were probably wrong. Yes, I know, you’re using an old claim that is universally accepted. Tough. The performance of epidemiology as a field has been so poor in the past few years that it now seems worth re-evaluating all their prior claims, especially claims that can’t actually be verified via the direct evidence of people’s experiences. That a link between smoking and lung cancer should exist certainly seems intuitive, but lots of bad COVID epidemiology seemed intuitive at the time yet the data made clear that it was wrong. If Fisher disagreed that the evidence was being used correctly, well, he was probably right!

You make some good points about the inaccuracy of modeling. I agree with those. But I think you are confusing epidemiology with causal inference. They are not the same.

Epidemiology uses both modeling and causal inference. Causal inference is a scientific tool used to analyze and build on statistics. It is not modeling.

Some epidemiologists have made models of how they thought this Covid-19 epidemic would progress. But models like those are just guesses, frequently useless (or even harmful), and have nothing to do with causal inference.

In the case I mentioned, Ronald Fisher pointed out that statistics cannot be used to prove causation. And he was right. They can’t.

Statistics can only show a correlation, or more broadly an association, between two variables. Statistics alone cannot show whether one variable causes the other. As Stuart McDonald says in this video, statistics can tell you what, they can’t tell you why.

Richard Doll and AB Hill accepted that you cannot infer causation from a statistical association. But they went on to ask, when can you infer causation? And in causally tying lung cancer to smoking, they started the development of a scientific tool that now helps us understand complex issues from climate change and epidemics.

Intuition and guessing (whether presented as a model or not) can be helpful in dealing with issues, but the more complex the issue, the less helpful they are. So-called Bayesian reasoning has the same problem.

Causal inference gives some mathematical rigor and objectivity to the process of trying to understand cause and effect. Unfortunately few people seem to know anything about it. Those that do are often outshouted by those who don’t know and don’t care.

What is the problem with Bayesian reasoning? I genuinely want to know.

I always find it strange how the ‘causal inferences’ (which is just another name for ‘unwarranted prejudices’) which people make always align with their political but especially moral views (e.g. ‘Smoking is a disgusting habit’. Well, not to me it’s not. Yes, smoking may kill me (practised for 56 years and counting), but breathing for long enough certainly will).

Now I make ‘causal inferences’ all the time, especially in relation to some religions and their propensity to foster (or tolerate) criminality. But the essential difference between ‘pro-vaxxers’ (or ‘anti-smokers’) and me is that my conclusions cannot be imposed, by law, upon others. I have no such power, and even if I did I’d be reluctant to use it.

“Richard Doll and AB Hill accepted that you cannot infer causation from a statistical association. But they went on to ask, when can you infer causation? And in causally tying lung cancer to smoking, they started the development of a scientific tool that now helps us understand complex issues from climate change and epidemics.”

To address this claim separately could you specify the precise nature of this ‘scientific tool’. What is the process involved?

I am sceptical because of a statistical study of death from lung cancer published in the Guardian newpaper 40-odd years ago (because ‘Clwyd’ was referenced it must have been post-reorganisation of the local Councils and Counties), being the work of two Americans.

Tables of cigarette usage were supplied for various regions of England and Wales (e.g. number smoked on average per day). This they claimed showed the clear relationship, expressed as percentages of people in each category of daily numbers smoked, between smoking and the onset of lung cancer. However on examination it revealed that people in Clwyd, North Wales (mainly rural, non-industrial) suffered lower percentage rates of lung cancer than people who lived in the major, heavily-air-polluted conurbations of England (Leeds, Manchester, Birmingham etc.) even though they were smoking identical numbers of cigarettes per day (whatever the number). In the entire study there was no mention of even the possible effects of the Clean Air Acts passed by Govt. in reducing lung cancer by promulgating cleaner less-polluted air.

The following week two British statisticians wrote to the Guardian rubbishing the findings of the previous week’s study (I can’t now remember the exact details of thier objections. but perhaps this affair lies around somewhere in the Guardian’s archives).

If the vaccines are saving lives, then why are excess deaths in Europe changed very little since the rollout? Why has the age profile of excess deathgs a lot younger after the vaccine rollout?

https://www.euromomo.eu/graphs-and-maps/#excess-mortality

Was it just me or did he sound extremely nervous of every word he spoke? I missed some of the beginning because I couldn’t stop laughing at the idea that a bank employee has no axe to grind! I have to say it wouldn’t be the first place I’d look for impartiality! If a banker told me it was Thursday I’d check my calender! Personally, I got nothing but an ear full of whitewash from this interview.

Pathologists In Germany have developed tests to determine the contribution, if any, of Covid vaccines to specific deaths. These tests are not conducted in autopsies in the U.K. Until they are, there is no way of knowing whether the vaccines were partially or fully to blame.

https://pathologie-konferenz.de/en/

Judging from their press release, they have done no such thing. They have tested for the presence of the spike protein. I would submit that the presence of the spike protein in a newly vaccinated person is not really surprising. Whether said spike protein had anything to do with the patient’s death, let alone how, is an entirely different question. It is of course not impossible that there is more to this, but given that the press release finds it necessary to talk about COVID “vaccination”, in quotes, I conclude that the authors are ideologically committed anti-vaxxers, and that any conclusions are suspect. I’d ignore this one until someone without preconceived anti-vax ideas has found the time to analyse it.

And, before you complain, the bios of the people involved seem to show that they are definitely experienced and competent. As we all know, that does not prevent them from being blinkered, ideologically captured, or wrong.

I guess you didn’t watch the presentation.

Indeed. I try to avoid videos and prefer text. Video takes too long, and it is too much hard work to blank out the emotional reactions and concentrate on the data content. Particularly if you do not trust the source so you need to be on the alert for misdirection. And if you do not have the background informa tion to judge claims up front. If there is indeed solid evidence of vaccines being very dangerous, the information will come out – from people who do not need to put ‘vaccine’ in quotes.

“the data consistently shows that the fully vaccinated have a lower mortality rate than those that are unvaccinated.”

This is the biggest lie of them all. Not starting tracking from the initiation of treatment and delaying it until two weeks after the second shot. Also my understanding is if somebody dies they are labeled unvaxxed unless proven vaccinated. This generally isn’t investigated so most of the deaths are labeled unvaxed.

Australia seeing something similar too

https://alexberenson.substack.com/p/urgent-deaths-are-soaring-in-one/comments

I listened to this today, and was amazed when the guest said ONS data showed higher death rates (ACM)in the unvaccinated consistently. So I went and had a look. They don’t. Not for all age groups: for my age group and younger (the under 50s), the least likely to die are the unvaccinated, regardless of number of vaccines.

For all age groups, the least likely to die (currently) are the triple vaccinated but most likely BY A HUGE MARGIN are those who have only received 2 jabs (I’m ignoring the 1 jab group as they are so few in number and could well have died from that first jab or they were too unwell to get another).

Either mr McDonald is an ideologue whose adherence to the narrative prevents him taking a close look at the data (or forces him to wilfully ignore it), or he is a very poor actuary indeed.

I wish you had quizzed him further on this.

Stuart should watch Professor Norman Fenton’s Nov. 18, 2021 YouTube video “Analysing Covid vaccine efficiency and safety statistics”. He questioned why there appeared to be a spike in unvaccinated deaths that correlated with the vaccine rollout for each respective age group. He determined that this could only be explained by the misclassification of recently vaccinated people as unvaccinated. Once this misclassification was corrected, the spike in deaths appears in the vaccinated , not the unvaccinated. Also worth watching is Dr. Fenton’s September 15, 2022 video, “How flawed statistics have manipulated the Covid narrative (Trailer)” , a short updated summary of his views to date.

I should also note that I originally tried to post this comment on YouTube and it was censored.

I should also note that I originally tried to post this comment on YouTube and it was censored.

Stuart should watch Professor Norman Fenton’s Nov. 18, 2021 YouTube video “Analysing Covid vaccine efficiency and safety statistics”. He questioned why there appeared to be a spike in unvaccinated deaths that correlated with the vaccine rollout for each respective age group. He determined that this could only be explained by the misclassification of recently vaccinated people as unvaccinated. Once this misclassification was corrected, the spike in deaths appears in the vaccinated , not the unvaccinated. Also worth watching is Dr. Fenton’s September 15, 2022 video, “How flawed statistics have manipulated the Covid narrative (Trailer)” , a short updated summary of his views to date.

By insisting with totalitarian force that everyone be vaccinated, we don’t have much of a control group to compare to.

And, as others have noted, the vaccines were NOT fully tested, they were rolled out based on very limited testing because of the sense of urgency. Prudent, normal practice requires several years but we compressed that to a couple of months of what look like pretty shoddy and flawed studies, no time to test for longer-term issues (among other apparent sloppiness or worse)–and now we are seeing what may or may not be longer term issuesthat we didn’t test for and with no ongoing trial and no control group–we don’t have a clue, nor will we soon get one.

Maybe we could stratify by the type of vaccine and other demographic factors to shed a bit of light, but basically we screwed the pooch on this one, as far as any statistical analysis..

As a statistician this interview was a huge disappointment. The Actuary report out of the US showing 100% more deaths than usual amongst the 25-55 year olds in Q3 2021 was a real shocker and should have started alarm bells ringing. I was hoping this fella could find correlations between that spike and the Q3 2022 excess death spike we are experiencing across Europe. But he seemed poorly informed, poorly prepared, and held strong opinions that was resulting in selective research. Real shame.

Hmm. Good questions, Freddie, but this fellow’s analysis strikes me as not very curious and enterprising.

Getting a hold of individual-level data would be awesome. (Lloyd’s doesn’t have access to some such data? Really?) Population-level data can’t enable to really come up with good hypothesis tests. But, such data can reveal patterns that make it hard to dismiss a role for either the vaccines or poor public policy in driving stubbornly high excess mortality.

I just posted this updated analysis using CDC data in the US:

The Fiction of ‘Sudden Adult Death Syndrome’ – A Graphical EssayBy March of 2022, rates of mortality appeared to have reverted to normal, but a closer look reveals all age cohorts have paid a heavy price over the course of two years of poor public policy.https://dvwilliamson.substack.com/p/the-fiction-of-sudden-adult-death

Maybe soon time for another go at this issue:

https://dailysceptic.org/2022/09/25/suspend-all-covid-19-mrna-vaccines-until-side-effects-are-fully-investigated-says-leading-doctor-who-promoted-them-on-tv/

So many other places appear to be censored. You need to return to this Freddie…

Maybe soon time for another go at this issue:

https://dailysceptic.org/2022/09/25/suspend-all-covid-19-mrna-vaccines-until-side-effects-are-fully-investigated-says-leading-doctor-who-promoted-them-on-tv/

So many other places appear to be censored. You need to return to this Freddie…

A member of the UnHerd Staff wrote, “And over the past ten weeks [British] deaths have been in excess by 15%.”

By contrast, the number of excess deaths was actually negative in 2020 for Japan. (See the reference.)

This result proves that proper behavior without a vaccine can limit the impact of the coronavirus. Proper behavior includes good personal hygiene and politeness (e.g., covering the mouth during a cough).

For a long time and without proof, supporters of open borders have claimed that multiethnic and multicultural diversity is the strength of the United States. The pandemic has proven that multiethnic and multicultural diversity is actually a grave liability. The number of excess deaths per capita in the multicultural United States is much greater than the number per capita in Japan.

Japanese culture is a Western culture. Japan is a mono-cultural society. In other words, a society with a single, dominant Western culture is superior to a society with a mixture of cultures.

Hispanic culture is quite different from Western culture. Hispanic misbehavior includes poor hygiene and rudeness (e.g., not covering the mouth during a cough) and produced a high coronavirus death rate. It greatly exceeds the Japanese death rate.

In California (where Hispanics are 40% of the population), by December 14 (2021), the Japanese death rate due to the coronavirus was only about 7.6% of the Californian rate, where “rate” is “death count divided by the population count”. Approximately 75,571 Californians succumbed to the coronavirus whereas only about 18,370 Japanese died from it.

Get more info about this issue.

“This result proves that proper behavior without a vaccine can limit the impact of the coronavirus. Proper behavior includes good personal hygiene and politeness (e.g., covering the mouth during a cough).”

We tried all the “proper behaviour” nonsense for over two years now, in many countries all over the world. It hasn’t worked in the majority of cases, so attributing the success of Japan to it seems kind of stupid.