Absolutely the last thing that Europe needs right now is another Eurozone crisis. Anything that destabilises the single currency, destabilises the European Union — and Vladimir Putin would just love that.

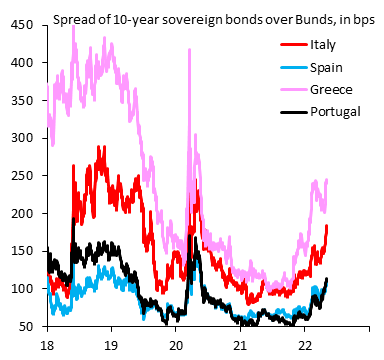

The danger in any time of trouble is that the markets lose confidence in the weaker Eurozone economies — especially those of Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal. The key metric here is the interest rate at which different members of the Eurozone can borrow from the money markets. If the difference in the respective rates for, say, Greece and Germany grows, then that means that markets see lending to Greece as increasingly risky.

If the gap or “spread” gets too wide, then lenders begin to worry that the weaker economies might default on their debts or even that the single currency might collapse. As we saw during the first Eurozone crisis, fear feeds upon fear, requiring extreme measures — like the permanent austerity programme imposed on the Greeks — to restore confidence.

Given the current talk of recession, is there any sign that a second Eurozone crisis might be brewing? A chart tweeted out by Robin Brooks shows that the spread between German government borrowing costs and those of the Mediterranean countries is getting wider again:

So far, the spread is narrower than the last time the markets took fright — i.e. the start of the Covid pandemic two years ago. However, the Eurozone authorities were able to provide the necessary reassurances and the panic was short-lived. In theory, they should be able to keep a lid on things this time as well. But there’s a complication.

In 2020, the European Central Bank — like central banks elsewhere — was able to use quantitative easing (i.e. money printing by electronic means) to fund the purchase of debt from Eurozone governments. But in 2022 there’s much more reluctance to use this option. That’s because of the danger of inflation. Unlike in 2020, there are no lockdowns to suppress consumer demand. Furthermore, there are multiple disruptions to the supply of vital commodities. This is no time for central banks to be funding public deficits with funny money.

So if governments can’t rely on quantitative easing, how are they going to survive a recession? They could borrow from the money markets instead, but that will put upward pressure on interest rates — especially in the most vulnerable economies.

Alternatively, governments could put up taxes and cut spending. However, countries like Greece have already suffered years of extreme austerity. To impose savage cuts at a time of faltering growth is likely to make any recession worse.

Of course, a currency devaluation would help — allowing a struggling economy to export its way to recovery. However, the Eurozone has taken that option away from its members.

Indeed, the EU appears to be rather short of options. At a time when Europe should be focused on external threats, it is once again distracted by its greatest internal weakness — the single currency.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeA fundamental problem with the Euro from the outset; one fiscal policy, undepinning one currency, over multiple different economies. The $ does this across the states of the US, but the $ originally expanded out from very similar Eastern seaboard economies and was not enacted centrally from above. I’d be happy to hear how other commentators think this problem can ever be resolved with changing the structure.

I have a good idea, self-sanction yourselves from you’re biggest and by far cheapest and most accessible energy supplier. Of course having no power to survive will help provide a recession to curb demand.

It’s at times like these that I wonder, again, if Brexit was such a good idea. Now we are no longer joined at the hip to the Mediterranean basin basket cases, are we now insulated? I suspect not. It’s not just a question of whether they can pay us what they owe if it all goes pear shaped, or the contraction of an export market that we may or may not service. For me, the question is the city, the square mile. Nations across the world pay us to help with the tech support for their economies (short version.) To be honest, I have no idea if that leaves us exposed. Although I have some economics training, and know that cheap, plentiful capital is leaving us when the baby boomers retire, but what really goes on in the city may as well be witchcraft to me.

Are we exposed? Is it possible to be insulated in a globalised world? And it’s not just finance, the Tories’ immigration policy was already looking threadbare, even before the return of good old fashioned geo-politics in the form of the Ukraine war. Were the goals of Brexit ever achievable? No, not really. But no one chose to listen to the adults in the room when the those questions were asked, we decided to listen to one Dominic Cummings instead. Look how that turned out. All the “adults” were purged and we now have a circus instead of a political process. How far we have fallen.