A contronym is a word that can be used as its own opposite — for instance, fast as in ‘go fast’ and ‘stuck fast’. Another example is cleave — which can mean to split apart or to bring together.

The most relevant example right now is sanction — which can either mean to allow something or to forbid it. The double meaning seems all the more appropriate when we consider the West’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

It’s not that the sanctions announced so far are meaningless. Many of them are already having an impact. Yet Europe finds itself in a position where it is trying to bankrupt the Kremlin while simultaneously bankrolling Putin’s regime.

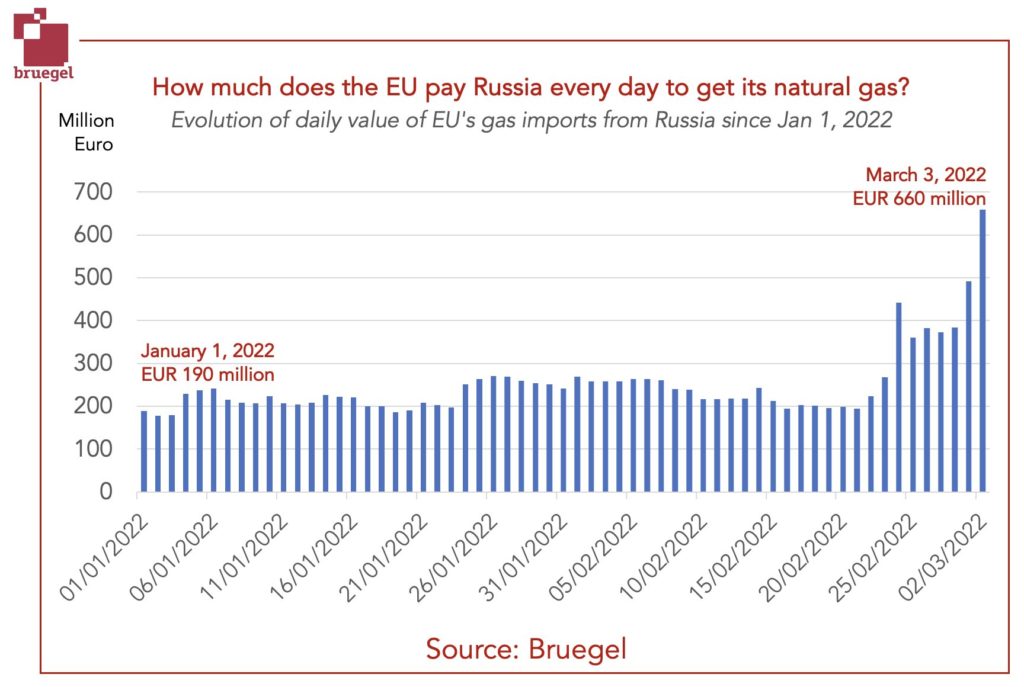

That’s because Europeans are still buying Russian gas and oil — and furthermore doing it on a colossal scale. A chart tweeted out by Simone Tagliapietra, a senior fellow at the Bruegel institute, illustrates the extent of the problem:

This shows the daily market value of the natural gas exported from Russia to the European Union. As you see, that value has gone up since the start of the invasion — a function of rocketing energy prices.

In a follow-up tweet, Tagliapietra explains that the price of gas via long-term contracts lags the ‘spot price’ — meaning that the exporter doesn’t immediately get the full benefit of any surge in current market value. However, the fact remains that the countries of the EU are still sending the Russians hundreds of millions of dollars every day.

And that’s just natural gas. Add in oil exports and that’s hundreds of millions more. So how do we shut off the pipeline of cash from Europe to Russia?

With great care. Western countries could restrict Russian energy exports or ban them altogether. Comments to that effect from the US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken were enough to send oil prices soaring above the $125 per barrel mark overnight. In terms of Russian revenues, higher prices could offset a partial fall in the physical volume of exports.

A better way would be to reduce the demand for oil and gas. In the longer term, that means switching away from fossil fuels altogether. But in the shorter term, we don’t need to find alternatives — we just need to use less.

Energy efficiency is an obvious no-brainier. There are tens of millions of homes across Europe that could be better insulated than they are. We could ramp up progress on putting this right in a matter of weeks and months — not the years and decades it takes to build nuclear power stations or develop a shale gas industry.

There are other quick wins we could go for. For instance, with hybrid working patterns established in many industries, a temporary shift towards more working from home would reduce commuting and therefore fuel use. Car pooling would also help.

I’m not suggesting any return to compulsory lockdowns. However, a voluntary national effort could make a difference. At the very least, we’d find out whether people were willing to do more than put a blue-and-yellow flag in their Twitter bios.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeIt does not take decades to develop a shale gas industry. Technically, at least. All the impediments are political.

Not only that but Cuadrilla have been investigating the Lancashire sites since 2011. Surely ramping up to full production can be done very rapidly with the right political support.

Technically yes, although Cuadrilla is a small company vastly outnumbered by even the smaller green groups.

See here from Feb 19th where they say reserves are vast but it would still take them about twelve months to get gas flowing:

https://cuadrillaresources.uk/cuadrilla-comment-on-jeremy-warner-article-frackings-false-hope-of-low-priced-energy-security/

Also, I expect a drilling and development surge in oil & gas worldwide as a result of Russia’s invasion, added to the post-COVID delays and shortages every O&G operator is already seeing. All the more reason to start soonest, of course.

Great article thanks. As it says just extracting 10% of the known reservoir of gas in theTrough of Bowland would supply the UK’s demand for 50 years and raise about £200billion in tax. Spend the tax on defence and we kill two birds with one stone.

FFS. Domestic electricity demand represents a minority of the total – industrial demand is far larger. Insulation and WFH orders would only reduce electricity demand by a couple of percent, if at all, and certainly not by enough to move the dial on prices – in Ireland, electricity demand actually rose in 2020, despite harsh lockdowns. And of course more WFH would actually increase domestic gas demand. It is ludicrous to hijack every world crisis to lobby for your own hobby horses, regardless of relevance.

Peter’s piece is a perfect illustration of how the commentariat are so far removed from industrial reality they think it’s all about home consumption.

Indeed. And in recent years data centres have become a new source of burgeoning electricity demand.

Simone Tagliapietra’s other article, https://www.bruegel.org/2022/02/preparing-for-the-first-winter-without-russian-gas/ cited at the bottom of Peter’s piece is a more sober account.

He proposes building up gas storage for next winter by obtaining more LNG.

Given that Europe hasn’t built enough LNG terminals, due again to Green-pandering political impediments, and they really do take years, if not decades, to get up and running, but more importantly, so do the contracts – even when built, the best adaptation of LNG will be by over the years diverting shipments meant for Asia, who will then have to get their gas from … guess where?

By which time the Ukraine crisis will have passed and something else will have us wringing our hands uselessly. (and declaring it’s the ideal time! to move to the latest green fantasy)

Let’s face it, the only effective opposition that will stop Putin will need to be military and nuclear.

He proposes …in Italian Simone is a man’s name, “Simon”. A woman would be called Simona.

Edited. And I thought I’d done well first time to intercept my autotype of Tagliatella.

Mille grazie.

Man, if only there was a massive untapped supply of gas in Britain we could turn to instead. What to do…

We don’t actually know how massive, or not, that recoverable gas from the likes of Bowland shale can be.

And we will never know, under the current drilling and fracking bans at national and local levels of government.

I think proposing the lifting of those bans in the context of the Ukraine war and raging energy inflation would be pushing at an open door.

I wouldn’t be so sure. As with every crisis, the green blob is trying to leverage this one into more public cash for wind turkeys.

What about ditching net zero and starting extracting where you can find the stuff in your home soil?

“I’m not suggesting any return to compulsory lockdowns. However, a voluntary national effort…”

Some people really enjoyed March 2020, didn’t they? Climate lockdowns seem mercifully to have died a death, so now it’s 3 weeks to beat the Russians.

A long, deep recession does wonders for demand destruction. Perhaps we should try that?

Rather obvious insights that I’ve already read in the MSM.

December 1989, as the people of Romania were freezing in their home and going hungry, then president Ceausescu famously said: put on an extra coat! He was killed shortly after

At least the summer is on its way. Turn off the heating; do not switch on the aircon

Agree but thinking very little air con in UK?

City offices, shops, warehouse shops; oligarchical residences in the south-east; you would be surprised!