Glancing over the latest panic-stricken headlines about Covid, it seems the end of 2021 has brought a whole new meaning to the phrase, the Nightmare Before Christmas. Just yesterday one Guardian headline read:

At this point, the general public could be forgiven for growing cynicism about SAGE’s supposed predictions. After all, when it comes to overshooting the mark, the advisory body has form. As recently as October, SAGE was reported to have predicted 7000 hospital admissions a day, a scenario which didn’t come close to materialising; in fact, admissions barely topped 1000.

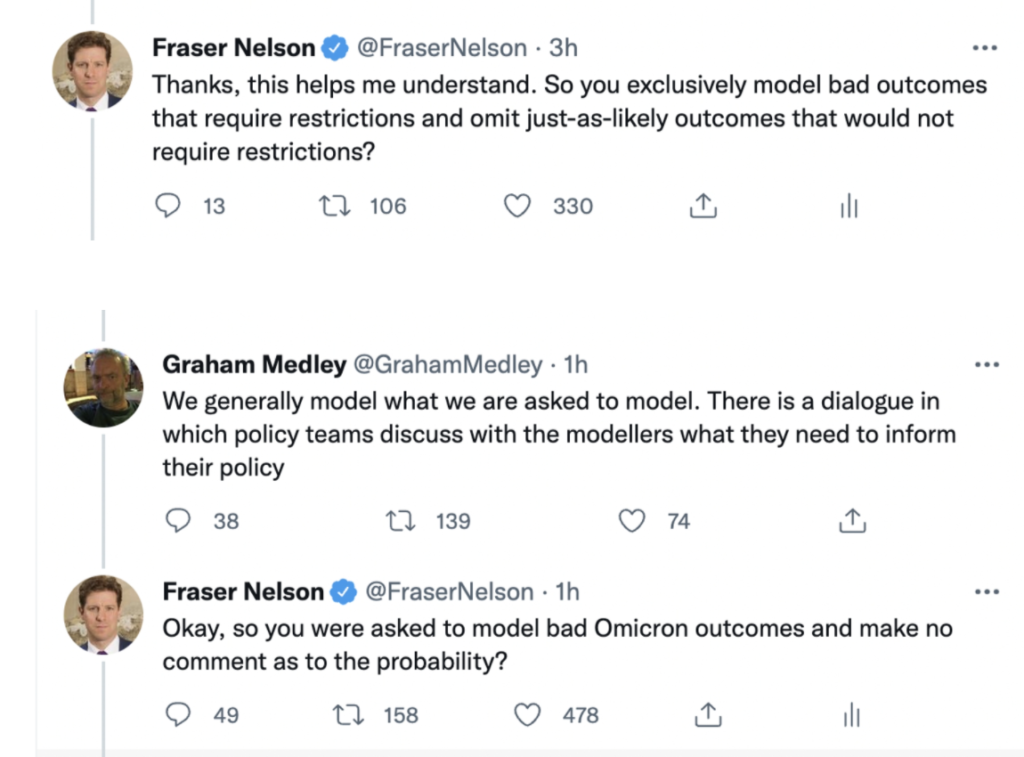

So what purpose do these models serve? Why are they always so gloomy? And why does there always seem to be little acknowledgement of how badly wrong they have been in the past? An illuminating Twitter exchange between Fraser Nelson, editor of The Spectator and Graham Medley, chairman of the SAGE modelling committee, SPI-M, may hold some of the answers. In the exchange, Professor Medley explained that the models produced by SAGE were “not predictions”; rather than models produced for a broad range of eventualities, their remit was far more limited. Policymakers discuss ‘with modellers what they need to inform their policy’ and models are created on the back of such discussions. Therefore, models are produced to ‘support a decision’ made by policymakers, rather than on the likelihood or plausibility of an event.

Typically, models are produced for worst case scenarios, which require decisions to be made and policy changes undertaken. For more promising outcomes that do not require a decision (or restrictions), models may well never be produced. As Prof Medley states: ‘decision-makers are generally only interested in situations where decisions have to be made’.

That modellers are producing only what is requested of them by policy officials should perhaps be no surprise. But this does raise questions about the drive towards negativity within government — how are sensible, objective decisions supposed to be made when the scenarios modelled are all ones in which intervention is needed — and therefore where outcomes are bad? If policymakers only ever request ‘pessimistic’ models, it is difficult to imagine how balanced decision-making can be.

There is another issue too. The models SPI-M produce do not exist in a vacuum. While Prof Medley may, rightfully, claim that the models created by SPI-M aren’t predictions or warnings, they are not treated as such by the media. Time and time again, the modelling produced by SPI-M has been utilised for alarmist headlines with dire warnings, which never materialise. Such coverage is leaving the public jaded and it is damaging our ability to respond sensibly to Covid.

All of this also ignores the harms created by restrictions, harms which have never been modelled. We still haven’t properly accounted for the damage caused by restrictions, and it may take years before we do so. Perhaps if as much attention was given to the damage caused by lockdowns as to improbable fatalistic scenarios about Covid, the Government and the public might have a better grasp on reality. The NHS would be better able to cope with the actual number of cases, and the UK, once again, wouldn’t appear to be on track for yet another lockdown.

Amy Jones is an anonymous medical doctor with a background in philosophy and bioethics. You can find her on Twitter at @skepticalzebra.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeSo far South Africa has not locked down. I heard via via that there was some pressure put on the health minister to introduce stringent restrictions, but he stood firm. I personally know quite a lot of people who have Omicron and many that have recovered. Even President Ramaphosa is back at work and he is in his 70s. Some have had very mild symptoms and some have a rotten time with a temperature for a few days (i.e. they have felt sick).

I think we will all be exposed to Omicron and I fully expect to get it. In the meantime people are out and about and personally I am socializing normally in the run up to Xmas (i.e. going out every night). No masks, no social distancing.

Do I want to get sick? No. But do I want to live my life in a mask and hiding indoors for an indeterminate time? Hell no.

Good for you! 🙂

Do you take your D, C, Zinc? Dr Campbell (who has really become a mouthpiece of the agenda now) still pushes them. As Hydroxychloroquine is prescription only I still think the early MedCram promoting of Querctin as a zinc ionaphore is worth doing, so I have a bottle of it too, as it is over the counter. (Medcram has become totally agenda since). Then you know I have my horse de-wormer, my bird azythromycin….

What bothers me is it is ‘Tempting Fate’, that very real Karmic thing of if you get a bit Hubristic you may well get knocked back – So I accept I may get croaked by Covid, and the embarrassment of going that way, as a Non’Vaxer, is as worrying as anything – but I am fiercely hard headed – and as I have come to believe the plandemic – wile a real virus – the response it utterly corrupt, so will not go along.

The facts: 0.23% UK’s current case fatality rate 19/12/21 – that means the chances of dying “with” Covid is 2.3 in 1,000 and that’s more likely to be because you’re obese, have vascular dementia or diabetes. We have nothing to fear other than fear itself.

SAGE and Fauci are merely the hired gunslingers of the global elites in their conspiracy to being the world to a new-Feudalism which they will rule. ‘You will own nothing, and you will have no power, you will be owned completely, and if you do as told, you will be happy‘

Was the full quote from Klaus Schawb (and mr Bigglesworth) of the WEF – but the middle bit got left out.

To prove this I VERY much recommend you watch this interview by Jo Rogan with Dr McCullough on how the entire epidemic became a Plandemic to push the Vax agenda for very nefarious purposes. It is 2 hours, 45 minutes, but is so interesting the time goes by fast….

https://brandnewtube.com/watch/the-full-interview-between-joe-rogan-and-dr-peter-mccullough_gMcVkA2Gb86n8iz.html

As Youtube immediately canceled the video it was moved to this platform – it is a bit slow, and you have to use the page back arrow to get by the sign up page – but then it begins, freedom of speech – after the censorship has been gotten around.

The premise is good medications exist if given at the onset of covid symptoms – Ivermectin, Fluvoxamine, Hydroxychloroquine, several steroids, and other things like monoclonal antibodies, and a big thing, Vitamin D, C, K, and zinc. With this cocktail the chances of ever getting to hospital reduce to a small amount. He says half of all deaths were easily preventable. Just take them and stay at home and get a flu and survive.

The medical advice was 100% NO action, just go home, and when your lips turn blue from O2 starvation as your lungs are filling – call an ambulance. DO Nothing, take nothing.

In NO medical situation is action not taken early, that the sooner the better the better outcome – BUT for Covid.

AND the reason was if people know there is a medical way to limit severe cases and death – they would NOT Vax. That is it – no medical response was allowed to be studied or used – because it would cause Vax Hesitancy – and the agenda was ALL GET VAXED – so hundreds of thousands were intentionally left to die, so the vax may be forced!!!!!!!

Bret Weinstein, who has been on Unherd 4 times, also did the same interview with McCullough, and it is still on youtube – it also must be seen, the same things said, but shorter – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-zg1j7Zquoc

You think this is real? This covid response destroying your children’s education, mental health – the health of everyone by missed medical, the entire global economy about to collapse by the results of lockdown and money printing, the millions of deaths in the third world from poverty by Western reduced economic activity, the loss of freedoms – and the mass killing by stopping medical treatments? This is the gift these modelers gave to the world – on orders from the global elites and their lackeys – the politicians.

With respect, may I suggest a better name for SAGE?

Churlish Unhinged Negative Twats

The acronym would be very helpful, as it would remove the somewhat positive though completely undeserved associations of SAGE.

Easy to remember

The first and last letters appear on the lateral flow test device with a gap for the missing two. Interesting.

By the logic of this modelling you would never get in a car, go on a plane or do anything that has even a modicum of risk. Hell, you wouldn’t even mow the lawn or put your trousers on whilst standing up.

SAndrew, you say:“By the logic of this modelling you would never get in a car”.

No. The modellers simply say: ‘Given the following assumptions (miles driven, speed, accident rate etc) our model suggests that the number of people dying in road accidents will be X’.

The government does not ban driving. It puts up speed limits, erects barriers, institutes driving tests etc – all designed to reduce the accident-rate.

Same with the virus. Policies are designed to reduce the likelihood of death/serious disease.

The big difference is that the modellers of car accidents are using years of data which is consistent over time. The COVID modellers are working with uncertainty, changing virus and will always have to model ‘worst case scenarios’.

I read about this Twitter exchange this morning. Thank you to Fraser Nelson for exposing the fraud that is Sage. I encourage people to read the Spectator article, or at the very least look at the full Twitter exchange between Nelson and the chairman of Sage – he links this to the Spectator article and it is not hidden behind a paywall.

This exposes more than anything else I have seen, the manipulation of the citizens of the UK during Covid.

He also wrote an editorial in The Telegraph, too.

Modelling is possibly the biggest farce in this entire charade. The worst forecasts money can buy, apparently.

Yes, a friend in London sent it to me, but I couldn’t open it…therefore I went sleuthing on Twitter!

Models are being used to predict other future catastrophes and always the worst are being used to promote fear, panic and the end of the world.

https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/my-twitter-conversation-with-the-chairman-of-the-sage-covid-modelling-committee

Thanks yes, this is the article I read. Jaw dropping.

Thank you for a sane evaluation of the insanity of SAGE modelling. It’s true that the media in particular loves to pick up on these figures as if they are fact. It’s very harmful on several levels.

Unfortunately, it’s not just the media. The government seems rather fond of the figures too.

from the way it is worded in the above Twitter thread, I think they specifically ask for the figures.

I declare shenanigans.

This has been happening in the Global Warming BUSINESS for years and it will only get worse if “we” keep going along with it. The trouble in the UK at present is that BoJo is getting advise from completely the wrong people.

“We generally model what we are asked to model”. Anybody need to know more?

and ‘We generally find the results we are asked to find.’

So doesn’t the blame lie mainly with the scientists that Boris brings on with him? They have regularly presented graphs based on these models on the basis of ‘this is what will probably happen if X doesn’t happen’ where X is eg lockdown. But according to Medley this is not what the models say but ‘this is what might happen in the worst case if X doesn’t happen; we have not been asked to investigate best case scenarios’. In other words we’ve been hoodwinked from the beginning by both politicians and CMO.

For anyone who hasn’t seen it, here’s The Spectator’s SAGE tracker.

https://data.spectator.co.uk/category/sage-scenarios

If the precautions the gloomy models cause result in huge collateral damage they are irresponsible and unprofessional. It is not enough to say they only measure covid. .

The quality of SAGE advice is so poor, that it really disqualifies the politicians who swallow it. It has been obvious since Prof Ferguson’s original scare scenario in 2020. He produces a bogus scenario, addresses it to the media, the media run with it because it increases readership, the government buckles. Why does this government buckle? Johnson is the answer.

I think many comments miss the point of the article, which is that the political elite do sometimes push scientists to produce data that supports decisions that they have already decided on. That is very dangerous. We have to produce accurate data, even if we do not like the results.

Johnson: the only way to save your premiership is to tell SAGE to go take a jump, and then wait to round on the Guardianistas as the scenario evaporates.

“SAGE’s doomsday predictions are damaging public trust” You can’t damage something that doesn’t exist.

So have any of you comedians here bothered to go and look at the SPI M O minutes or the SAGE minutes or the 2 pre prints detailing the models referenced ?

Just to save people the bother, the LSHTM & Stellenbosch model give 4 different scenarios with various combinations of immune escape and booster efficiency with confidence intervals and then a whole raft of sensitivity analyses looking at other factors. Best case scenario ? – hospital admissions between 1,500 – 3,000 / day in late January

The University of Warwick modelling looks at various severity / increaseing VE against severe disease scenarios along with the date of application of more restrictions and the compliance with those restrictions along with booster roll out effects, again, all with confidence intervals. Best case scenario ? – hospital admissions 500 – 1,900 / day by end of January

So … by all means lets be all Swedish about this and let people make their own decisions.

Easy to read graphs throughout. Enjoy.

As for costs versus benefits of restrictions, well Imperial produced a paper on this in June last year (freely available for all to view).

Glad you refer to everybody as comedians, especially since you are hardly an authority on the subject, given that you specialize in one specific aspect of dentistry, namely periondotics (and yes I looked you up on Google, and your research track record is also very meagre with only 8 published papers apparently). Every single prediction made by SAGE, Imperial College and all the other poobahs was and continues to be way overestimated in terms of negative outcomes and has only engendered fear and hysteria. When the predictions don’t materialize and the mitigation efforts are clearly completely useless (did they prevent waves – no; did they prevent rise in cases – no; did they reduce deaths – no; was the NHS or US health service every overloaded – no; are there any significant differences between lockdown/mask states versus those that are open, didn’t lockdown and don’t have mask mandates – no). So what exactly are you talking about Elaine other than suggesting more of the same failed policies and expecting a different result – the very definition of insanity. Time to learn to think critically rather than just regurgitate talking points determined purely by confirmation bias and trust in the public health authorities who have managed to get every single decision wrong.

Now at the beginning I’ll fully admit that Government officials were caught between a rock and a hard place. They would have been attacked no matter what they did in the press, and indeed they were. But the truth is that no matter what they would have done, the end result would have been the same. The only thing that one could do is apply some very simple, common sense measures and trust the street smarts of one’s own population (as was done, for example, in Sweden), and perhaps try and increase ventilation in indoor spaces by facilitating the installation of high capacity HEPA air purifiers.

Now consider schools and school children. In Sweden the schools were open and nobody suffered. Elsewhere they were closed with devastating effect, especially on the segment of the population that could least afford it. Now consider masks in schools. I believe that a recent study out of the UK showed that while masks appeared to offer a modicum of protection in terms of reducing spread among school children in school (who are not in the at-risk demographic anyway), no difference between masked and unmasked was observed when the windows were open all day, and even opening the windows for 15 min reduced any difference to negligible levels. So when one has an observation such as that, then why not install a high capacity HEPA filter in each classroom – sure they cost around $800 to $900 but Governments could easily have negotiated a massive discount. But has this rather simple intervention which entails absolutely no inconvenience to anybody been done – and the answer would be no.

8 papers published is more than 99.99% of us have – and shows the poster has a great deal of qualifications. And I have a problem with doxing …

Hardly doxing when the information is available to anybody for free with one click in Google! And while 8 published papers is for sure more than 99.99% of the population, among academic scientists it is a very very low number. I pointed this out because Elaine was conveying a degree of scientific knowledge and authority which she doesn’t possess, but she was perfectly willing to use that impression to trash any viewpoint that went against the accepted “Thesis” position of instituting medical totalitarianism. If the “Thesis” position had actually worked or was actually shown to be working, I personally would be only too pleased as I’m sure everybody else would. But, unfortunately, the “Thesis” position has been proven wrong by events time and time and time again, and all the Thesis side does is attempt to reinstitute mitigation measures (jncluding more vaccine boosters, masks, lockdowns, etc…) on the belief that this time they will work – but as Einstein said that’s the very definition of insanity. What’s clear to me (whether I’m qualified or not) is that it’s time to take a step back and truly reassess the situation and how best to approach things. Perhaps, just perhaps, non-intervention coupled with some common sense, as in Sweden and indeed now in South Africa, is the way to go rather than beating a dead horse as the US and UK public health authorities are currently doing (not to mention many in continental Europe as well).

To a large degree I think the West is a prisoner of their own biotechnological prowess. If they couldn’t mass test people with no symptoms and if they couldn’t sequence every SARS-CoV2 viral RNA that they pick up, we might be a lot lot better off in terms of public policy. Sometimes over-reliance on technology is a bad thing as the US found out in Afghanistan where they were defeated and utterly humiliated by a bunch of goat herders.

Good to know that you use Google from time to time Johann.

So I said “Let people make their own decisions”

Sweden had no in person teaching for upper secondary students and University students in 2020 from March until around September / October and then shut the upper secondary schools again in December.

HEPA filters are terrific, that’s why I am not particularly bothered about flying on aeroplanes.

Models, except in very specific circumstances are not designed to predict. As it happens, the infamous graph that Whitty and crew showed on October 31 2020 showed graphs produced by 4 different modelling groups (with confidence intervals which of course the MSM ignored). Where the 4 CIs intersected on January 1 2021 they modelled deaths at around 1600 (range of 800 – 3,500) and guess what ? on January 1, deaths were around 1100 so on that occasion all in the ballpark.

Maybe we’re not so far apart after all, although I really do think that you convey a good deal more expertise on the subject matter than you actually have.

Nevertheless, I find the “Thesis” position deeply unsettling when an article in the BMJ detailing the various wrongdoings and poor practices in the Pfizer phase III trial were labeled as false information by Fact checkers on Facebook with Facebook effectively equating the BMJ to the National Enquirer.

I also find it deeply worrying that, if I recall correctly, both you and Rasmus were dismissing the significance of myocarditis post-vaccination. You should know as well as anybody that if those types of adverse effects in the frequency of current occurrence had occurred with any other vaccine at any other time, that vaccine would have been immediately withdrawn from the market. Further, while you are not a physician but a dentist, you should still be aware that there is no such thing as mild myocarditis that entails hospitalization for a week (or even a day for that matter) – a significant fraction of individuals who apparently recover will still have reduced ejection fractions compared to their state prior (even if in the lower range of normal) and are quite likely to end up in heart failure when they get to their 50s, 60s or 70s. And for what: a disease that is essentially of non consequence to the relevant demographic (young boys and men between the ages of say 11 and 30).

As for ranges, you will note that the newspapers and TV news never report the ranges: so yes 1100 predicted deaths is within the 800-3500 range but the number that gets reported for the prediction is 1600. The number the politicians hear in the summaries they read is 1600, not 800-3500. Further 800-3500 is an awfully wide range upon which to base severe restrictions such as lockdowns, and mask and vaccine mandates don’t you think? It’s a range that has absolutely no value and could have been plucked out of thin air without any mathematical modeling. And that’s especially when those interventions appear to have had no significant effects on every single COVID wave to date. In other words, no intervention or mitigation effor has had any significant effect anywhere – which is sort of self-evident when one compares the different US states which are much of a muchness.

And lastly, the current article article in Unherd was reporting on exactly what a very senior person in SAGE was actually saying about their modeling: specifically they design their models and obtain the results that would make the politicians institute a particular set of policies. i.e. give the policy and they’ll find the appropriate model and prediction. Sort of like the famous Beria quote isn’t it: “give me the person and I’ll find you the crime”. That sort of modeling is totally inappropriate and irresponsible and leads to irrational public health policies, not just in the UK, but in the US and most of mainland Europe.

Deaths were 748 in January 1st, that’s according to the NHS website based on date of death.

Can you let us know your qualifications, Johann?

Just out of interest I find it creepy that Johann Strauss, a brave man not revealing his name, goes to the trouble to look you up.

Not creepy I hope is that we share an interest, according to one of your posts. Did you see the end of the 9th game which Magnus won easily. He shook hands with Nepo and walked out of the auditorium to be beset by reporters. The first was Norwegian but the second pushed a microphone into his face and said, “Did it change your strategy when you saw that your opponent had changed his hairstyle?” Magnus, as always, was very professional.

There are many people who are speaking out that have to use assumed names. People are losing livelihoods. There is absolutely no problem using your own name if you are supporting the accepted narrative and toeing the line:

Lockdowns are good, vaccines and masks are good, expensive medicines are good (cheap medicines are bad). Big pharma, the WHO, the FDA, Sage and the like are good. Corporate media is fab. Facebook fact checkers are great. You get the gist…

Dexamethasone is as cheap as chips.

I don’t recall ever making a value judgement about either full on restrictions or face masks – only comments about the quality of some of the studies available ditto for some of the drug studies.

I have already replied to you about big pharma – a dysfunctional business model.

People can read SAGE minutes et al and make up their own minds.

There is a very good reason not to use my real name. As for Elaine, while everybody is entitled to their own opinion, nobody is entitled to their own facts. No doubt Elaine is reasonably well informed but a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. Further she appears super critical of any “non-Thesis” viewpoint with numerous nit-picking comments delivered with a tone of great authority and expertise and apparent great knowledge of the virological and immunological literature, which clearly give the impression of having a lot more knowledge of the subject matter than she actually has. (And to be fair most practicing doctors and dentists have rather limited scientific knowledge).

The really unfortunate thing in the current climate is that the “Thesis” just invents their own facts and then tries to bludgeon these facts into everybody else, even though it is quite evident that their facts simply don’t add up. I wish they did but they don’t. If they had, Covid would be long past us, and nobody would be writing articles on it or discussing it on a daily basis. Further, when the “Thesis” loses somebody like Paul Kingsnorth, one should know that there are clearly some major issues in their positions. Kingsnorth is clearly not some extremist or fringe philosopher; rather he is a very intelligent person capable of critical and insightful thinking.

Further, the “Thesis” continues to distort the language in truly an Orwellian manner. One can say 2+2 = 5 all one wants, but that doesn’t make it so. So, the Thesis can say that the vaccines are safe and effective, but any type of critical look at the data indicates that in normal english usage they are neither: (a) the vaccines lose their effectiveness after 6 months; (b) medium term, let alone long term, adverse effects have not been investigated; (c) anything that might point to issues with the vaccines are dismissed and worse censored (and there are plenty of things to be concerned about in terms of adverse effects and the risk/benefit analysis which may vary from individual to individual); (d) any alternative perspective is again dismissed and censored (e.g. Collins dismissing Gupta, Battacharya and Kuhldorf as fringe epidemiologists, and organizing a put-down of these highly reputable investigators and highly reputable institutions without taking the effort to seriously argue their points); (e) bad predictions are exaggerated by orders of magnitude for the sole purpose of instilling fear and panic in the populace (so as “not to let a good crisis go to waste”) – these leads effectively to dictatorship by the “Thesis” medical authorities who claim, as did Fauci, that they are “the science” and anybody who criticizes them is a “science denier”; (f) and lastly the hoodwinking of many intelligent people into simply believing that Government and Government experts must necessarily be right and have our good interests at heart (the nanny syndrome). With regard to the latter, Rasmus is a classical example – he is clearly very smart, from what he has said in various posts was clearly involved in some high level mathematical research, but he simply refuses to see what lies directly in front of his eyes if he actually chose to look carefully. He naively believes that the Government and public health authorities will openly investigate any adverse effects of the vaccines, for example, rather than just deny, deny, deny and try to cancel anybody who points out otherwise. He will blindly support boosters although there is absolutely no real world evidence that boosters are either effective or if effective how long they will be good for. And yes boosters boost antibody levels but that is far from the whole story. Producing large amounts of antibody targeted against a spike protein that is no longer in circulation in the hope of neutralizing a virus with a spike protein with hugely reduced affinity for the vaccine-induced antibodies just defies any sort of common sense, and moreover is fraught with very high risks. (And suffice it to note that 2 US senators and a congressperson were just diagnosed with COVID over the weekend despite being triply vaccinated).

No ! I missed that – will go back and look for it. Thank you. I have watched Magnus almost being trounced by a 16 year old online, however, in a blitz game – he was very gracious. He was playing challengers one after another while cooped up in what looked like a not very upmarket hotel room.

God, what a life ! I wonder if he gets any fresh air and sunshine ?

Great to hear a sane voice among the others here, Elaine.

My own take (as a former secondary science teachers) is that there has been a monumental failure to impart the basics of the evidence-based method which has created the modern world.

Until recently, the general population have been happy to accept the findings of the scientific community without feeling the need to understand the reasons.

We, the empirical community, have not noticed this. We have not made sure that there is at least a minimum understanding among a minimum of people.

We are now reaping the damage of self-styled ‘experts’ who take one line from a text and interpret it as a conspiracy.

Ho Hum. End of Modernity summons and the re-emergence of the Medieval mindset.

The problem is not the modelling itself, it is the selection of a “scenario” to be modelled. What is a scenario? It is a story created by someone based on assumptions that someone makes about the future. It is only after that scenario is created that it is modelled mathematically. If the model is to be used in setting public policy, especially something like a lockdown, the modeller should be required to disclose the scenario to be modelled and who created that scenario, on whose instructions. This type of legislation by scenario requires transparency, not opacity.

You seem to misunderstand the nature of models and their output.

A model is just a set of equations developed using the best evidence available.

They do not make ‘predictions’ as such. Modellers do not say ‘This will happen’. They say: ‘Given these assumption and this data our estimate is …’ It is then up to ministers to take the decision.

When Medley says ‘We generally model what we are asked to model.” he doesn’t mean he builds a model to give the government the answer they want. The model is already built, they simply use it to ‘model’ what might happen under sets of circumstances.

The fact that the journalist present these findings as ‘predictions’ just shows their ignorance.

However, the modellers are also culpable for not explaining what they are doing to the untrained journos and politicos.

For example: modellers are criticised for ‘predicting’ that there would be 500,000 deaths from COVID. They didn’t say that is what would happen, they simply did this calculation:

Interesting. And it does sound like it would be useful to know more. But it raises a very curious question: If it is indeed true that SAGE is being deliberately asked to produced extra-gloomy information, who is doing the asking? Not SAGE. Not the government – the Boris would obviously love any excuse for postponing restrictions till after Christmas and make everybody feel good. Do we really need to assume that there is a subversive cell in the civil service deliberately trying to ruin the British economy? More realistically: Who is taking the decisions? Presumably the government. If they need more information, why are they not asking for it? Too incompetent? Or is this just the kind of misunderstanding you get when all you have to go on is a couple of tweets?

Would you not agree that SAGE’s modeling have a 100% track record of being way off on the pessimistic side. Would you not agree that the current wave of pessimistic outlooks in the UK and the US is not helpful to public policy decision making and engenders panic on the part of Government ministers. In the US we have “senile” Biden and as late as yesterday, Collins the NIH Director, on his way out, claiming we’re in for a world of hurt this winter with Omicron. Only problem is that the data both in South Africa and Denmark indicate that Omicron is a good deal less pathogenic than previous strains – i.e. many fewer hospitalizations, essentially no (or very few) deaths, and symptoms of a bad cold lasting all of 2 days. One really has to wonder just exactly what’s going on. Perhaps Collins gave us a hint when he referred to Dr.s Battacharya (Stanford), Kuhlsdorf (Harvard) and Gupta (Oxford) as fringe epidemiologists who weren’t qualified to analyze the situation, as if Collins and Fauci, with no background in epidemiology were. (And since when are full professors at Stanford, Harvard and Oxford ever fringe). It’s as if we’re living, in most Western Countries, in Alice in Wonderland.

On public policy I am with Tom Chivers: If there are very bad and fairly likely outcomes it is better to take precautions that might prove unnecessary than to just assume that everything will be fine. So, no, I would not agree with you. I would like to know, though, whether those who have to take the decisions are getting correct information about the various possibilities and how likely they are – and if not, why not.

No, it’s not better since the result is causing widespread panic, confusion, with disbelief and non-compliance with measures implemented. Better to follow Sweden’s example with modelling of alternatives to support the health service’s planning and not for spewing out curves and projected statistics for public consumption. Even Sweden’s modelling has proved wrong, eg. autumn 2020 was a lot worse than their worst scenario, but it wasn’t the end of the world. They got through the wave without the health service collapsing and avoided the disproportionate and ridiculous measures as inflicted on the UK. The Swedish public health authority are being criticised for reacting too slowly and not enough but reactive and considered judgements are a lot better than scaremongering and panic.

You say, ” it is better to take precautions that might prove unnecessary than to just assume that everything will be fine. ”

That assumes that the precautions are “free”, but we know they aren’t.

Why don’t they produce scenarios on the side effects of restrictions? For example, the effects on inflation, as this is a number easier to quantify. We could have a scenario whereby you get inflation at 20% if you do X or Y. Or a scenario that talks about job losses or business failing and that scenario says that hospitality ceases to exist if you do W or Z.

They says they should, but AFAIK, no-one is.

Rasmus has long been dismissive of the cost of restrictions and lockdowns. People losing businesses, many plunged into poverty and desperation, children losing years of education or lost to the education system entirely – on it goes. I cannot fathom it. I think he is distanced from the impact of the fallout on economies.

Lesley, he is just representative of many who do not feel themselves to be harmed by restrictions either materially or emotionally. Those who would keep us in limbo are often fond of accusing those who do not of selfishness when in fact, theirs is the greater degree of selfishness.

To all of you: Admitted, I am not much harmed by restrictions. And yes, you do have to consider economic trade-offs, as well as health ones. But I would be more impressed with someone who said openly “We need to keep the hospitality industry open, and we are willing to accept 10000 premature deaths to achieve it”. I think most of you are quite as dismissive of the cost and dangers of COVID as I am of the cost of fighting it.

For the rest, it is not a question of never taking risks. but of deciding which ones to insure. Personally I have home insurance, travel insurance, but not warranties on white goods – even though I know that statistically I would be better off having no insurance at all and not contributing to insurance company profits. Personally I think moving to plan C in the UK two weeks ago, but not into full lockdown, would have been an excellent insurance policy.

It is simply not true that I (and others) am dismissive of the cost of lives lost to Covid. I am however logical and can figure out that far more lives (and livelihoods) will be lost because of lockdowns. This will be felt for many years to come. 250 million pushed into poverty and counting. Where are the shouty progressives regarding this?

Bearing in mind that it has been clear from the beginning that the elderly and those with certain co-morbidities are far more at risk, it has always made more sense that those should be the people who should take precautions – if they want to. Many elderly people would prefer to take the chance of seeing their loved ones in the last months and years of their lives.

What has been visited on the world is criminal.

It seems to me that you are really blind to what is actually happening in the real world and the actual results of all the various mitigation efforts that have been put in place. You are like the person with blinders on who says “see no evil, hear no evil, move on nothing to see here”. As a result your suggestions are simply to do more of the same while expecting a different result – according to Einstein that’s the very definition of insanity. So how about we just take a look: masks – no apparent effect on slowing things or preventing new waves; lockdowns – no correlation with cases or waves, i.e. no practical effect whatsoever; vaccines – initially seemed good but now are clearly failing, and not only that but the boosters are clearly failing as well (indeed, over the weekend, 3 US senators all fully vaccinated and boosted have announced that they have tested positive for COVID – so much for their booster shots).

Isn’t it time to take a step back and really assess the situation and stop playing theater and virtue signaling?

So what does this mean in practice. (a) It is not unreasonable that if one can work from home it’s not a bad thing to do (plus it reduces traffic congestion); (b) stay out of crowded, poorly ventilated indoor spaces if one is worried about catching COVID; (c) install high capacity HEPA air purifiers/ionizers in indoor spaces wherever appropriate (as they have indeed done on planes); (d) treat people like grown-ups and let them make their own decisions; (e) forget about vaccine mandates and passports and changing definitions of what does and does not constitute full vaccination status – all this does is divide people; (f) only vaccinate and boost the most vulnerable (i.e. the elderly and those with severe associated co-morbidities) which will remove one of the drivers of new escape variants. Clearly mass-vaccination in the middle of a pandemic with a vaccine that is not sterilizing was not and never was a smart move but a monumental error of judgement.

I don’t necessarily agree with him but I can see his point.

Everybody on UnHerd could be called ‘strong’ – I mean clever or able or good at thinking. Therefore they assume everybody will be the same. Probably UnHerd types represent 0.5% of the population. If they have friends, they will be strong as well. But most are weak.

Weak people do what is socially acceptable in their circle. If there is a virus which can strike them down they will not change their habits until they are frightened. If governments today lifted this fear there would be no way back. It is a tool of domination but, arguably, it is done for a good reason.

In the UK, the vast majority of older people are fat. Not just a few but millions. To say that Covid only causes problems with the obese means millions of problems. Any normal leaders would not take this risk, even if it was very unlikely.

It is completely different just to have a personal opinion on the one hand compared with looking after the health of millions on the other. The UnHerders would not survive for 5 minutes if they actually did the job of governing.

One example of a flaw in your argument – let me point out that the obese have plenty of health problems besides Covid. They are marching fast towards their end and they know it. What is your friendly uncle the government doing about this? Regulating the food industry?

As I said, you could spend all day commenting but what use is it? I think it is so you use your education and feel special.

Indeed. A model showing the worst case scenario of a crushed economy may well show millions of people moving into extreme poverty, collapse of infrastructure, with all it entails and possibly famine. Not likley to happen, but it could. So surely we should mitigate against that?

And that’s about as much effort as SAGE seemingly puts into anything.

Maybe because any such scenarios would have been 100% guesswork, much worse than any COVID predictions?? You do need to consider the costs, but modelling does not sound like the way to do it.

This is where you are 100% (no 1000%) wrong, and you fail to understand the real world. If one were to take your advice one would never get in a car or fly in a plane; one would also wear a mask at all times of the day just to avoid a cold or the common flu or any number of other respiratory tract infections out there. Probably worthwhile you re-reading (if you’ve ever read it) “Peter and the Wolf”. One can cry wolf just so often and after a while no one will believe you, and sooner or later the common people will realize that the leopard has no spots.

The key point is that one has to give the correct advice and a reasonable perspective. Not predictions that are way way off. Those are unhelpful and only engender fear and hysteria, and ultimately the breakdown of civil society. Sooner or later the public will have no confidence in anything coming out of the mouthes of Public Health Authorities. And listening to the interview that Collins gave yesterday, I suspect that very soon nobody will believe anything coming out of the mouthes of NIH, CDC and FDA officials.

I used to make brave statements like this about cycling. Why spoil your enjoyment by wearing a helmet? The odds that the helmet will come in useful are negligible.

But this is only true if you personally are not involved in the serious accident where someone’s head is smashed in. If you are involved it could destroy your life and your family’s existence.

You quote all of these odds but you know nothing about life.

To be honest I’m not sure what you’re getting at, especially since I haven’t really quoted many odds.

Interestingly I happen to be an avid cyclist as a hobby. When I was young, and before cycling helmets were a thing, I obviously didn’t wear one. Now I do. Actually wearing a cycling helmet does not spoil my enjoyment of cycling at all, if anything it enhances my enjoyment. (But I don’t think masks enhance anyones enjoyment of social interactions). But it would be interesting to know how many serious head injuries from cycling accidents have been avoided because of helmets. And I’m saying that as somebody who has had their fair share of crashes and broken collar bones and ribs (even though neither my helmet nor the bike even sustained a scratch in any of those).

The issue, however, with regard to COVID is what, for any given person depending upon their circumstances, is the appropriate risk/benefit ratio. Are the risks of COVID vaccination (such as myocarditis in young boys and men which is not that rare given the incidence of somewhere between 1 in 2000 and 1 in 5000, depending on the study) worth taking for an individual who is at minimum risk of any untoward effect from a COVID infection. It’s a choice each individual has to make for themselves. But what is absolutely clear is that when you have a vaccine that doesn’t prevent transmission, it’s only purpose is to protect somewhat (e.g. reduce disease severity) the vaccinated individual. So a mass vaccine mandate makes absolutely no logical sense. Likewise take masks. Regular surgical and cloth masks never offered any protection although that’s why people, deep down, are wearing them. What they were supposed to do is prevent transmission as a method of source control. But real world data suggests that the effect, if any, is rather small (10% according to the 350,000 strong Bangladesh study run out of Yale and Stanford, and ignoring any of the major issues related to the study design). And what about lockdown. Keeping people in their houses rather than allowing them to enjoy the fresh air, especially in wide open spaces with nobody around, can’t possibly be regarded as sensible public policy.

And do you really believe that wearing a mask in a car alone is the sign of any sane individual, and yet I still see many who are doing just that where I live. Simply boggles the mind.

“it is better to take precautions that might prove unnecessary”.

Well, perhaps. But ‘precautions’ aren’t cost-free. They come with their own costs – potentially huge & very damaging ones. And it seems that much less consideration has been given to them. The monomaniacal obsession with Covid has pushed everything else aside.

It is not just a ‘couple of tweets’. On Twitter it is an extended number of tweets with Nelson trying to get Medley to tell the truth. At the end of the exchange it is very evident where the truth lies. The instruction was to manipulate the outcome of the data.

There are a couple guys popular on youtube – the 4Th Turning guy, and the ‘Group Formation’ guy (or herd formation – I forget) but basically they talk of how societies get in sync, like the example of Germany in 1932, and begin to coalesce around some principal and charismatic leaders and sanity is gone, and war is inevitable….

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K8Ndnpfw69w

Like this guy – I do not care for him actually, but he gets around a lot – I know history and people better than him – but there is smoke, and so some fire….

PS, love your lone stance here Rasmus, good for you.