All around the world, public sector borrowing has gone through the roof to pay for the costs of Covid. Ultimately, it’s us — in our role as taxpayers — who’ll have to pay it back.

But what about private sector borrowing? Companies have also had to rely on credit to get them through the crisis. That’s something we’ll have to pay for too — only this time in our role as consumers and workers.

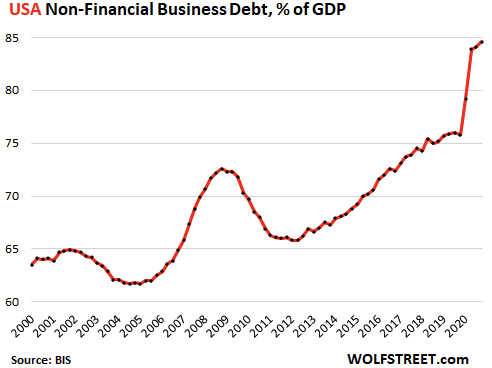

So how bad does it look in each country? An eye-opening post by Wolf Richter on the Wolf Street blog provides the answers. For instance, here’s the chart for America:

As you can see business debt suddenly spiked upwards last year by nearly 10% of GDP. That’s on top of a pre-pandemic borrowing level that was already at a 21st century high — higher, in fact, than during the Global Financial Crisis.

Furthermore, these figures exclude financial businesses like banks — so we’re not looking at some artefact of high finance here.

So is America an especially bad case? Not really. For instance, business debt levels as a proportion of GDP are almost twice as high in China.

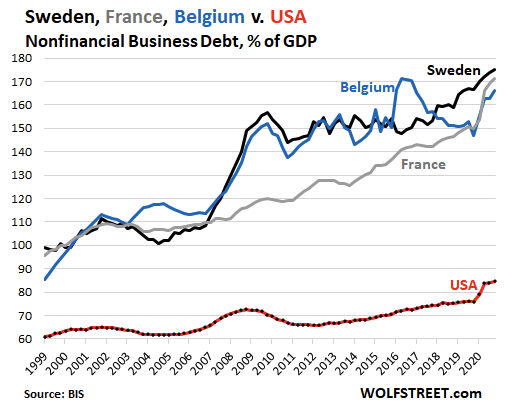

The most indebted countries of all are tax havens like Luxembourg and the Republic of Ireland, but those are special cases. A more interesting comparison is with Sweden, France and Belgium — all of them ‘normal’ economies, but with deeply indebted businesses.

In the French case, Richter points out that many of these biggest corporate debtors are partially state-owned — which has clearly done nothing to discourage lenders from pumping them full of credit. At least, not so far.

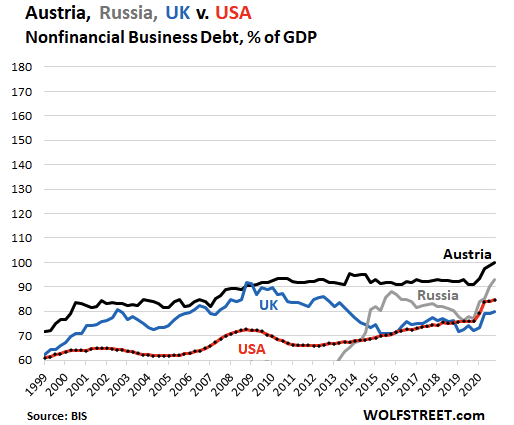

Where does Britain stand in these comparisons? Well, over the last decade our business debt levels have been in the range of 70 to 80% of GDP — so we look a lot more like America than France or China. As in most countries, there’s been a Covid spike in business borrowing, but we’re still well below where we were at the time of the Global Financial Crisis.

We should of course be concerned that Covid has driven British companies deeper into debt. Though the global supply credit is ample, it is not limitless. Like all things that can’t go on forever, at some point the trend towards growing indebtedness has to stop.

That said, this is also a game of comparisons. Money markets are more likely to keep lending to countries whose debt levels look sustainable. Of course, quality matters here as well as quantity: borrowing to improve business productivity ought to inspire more confidence than borrowing just to stay afloat.

Brexit Britain therefore needs to stay ahead of the game on both fronts — basic solvency, but also long-term investment.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeI will make a bet with anyone willing to take it – this supply side crunch, shortages, ramp in work, projects and employment, rising inflation etc, is a dead cat bounce, not the start of a long term boom. Once it is over, perhaps 18-24 months, the mother of all depressions is coming. The second half of the twenties is going to be very very horrible indeed. My opinion only of course.

I haven’t seen enough data so suggest a dead cat bounce or a long-term boom, so my guess is short term inflationary boom while supply side ramps up again, then business as usual.

QE levels will surely be what makes the difference …

On QE, the question is: haven’t they all shot their bolt? All out of ammo, except perhaps China.

I wish I didn’t agree with you