Each generation has its own moral panic about emerging technologies. Silent movies were said to provoke crime; violent TV and, later, violent video games said to cause violence.

Forty years ago, we had a debate in Parliament about the harmful effects of ‘Space Invaders and other electronic games’ on children. These days it’s social media. It’s seen as addictive, tuned to hot-wire our brains’ reward functions. We talk of social media hacking our dopamine systems, as though it’s a drug. And, of course, as it does so, it is damaging us: making us depressed, lonely, anxious.

The trouble is, no one keeps their eye on the ball: as each new technology comes out, we forget the last one. But violent video games haven’t gone away. In fact, they’ve got rather better. There was a huge scare about Doom, back in the early 1990s; but if you play it now, it’s almost laughable. If its crude, blocky, pixellated graphics could inspire a generation of children to violence, what might Apex Legends be capable of? Or Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War?

The same with movies, TV, adverts: presumably, the people making them have got better at their jobs over time, and the technologies themselves have improved.

There’s a new paper out in the journal Clinical Psychological Science which points out an interesting corollary to that idea. If these technologies really do have these negative outcomes for us, and if they are, as they surely must be, improving over time, then shouldn’t the negative outcomes get worse?

To use a video games example again, because I find it easiest to understand: if it’s the realistic depiction of violence that’s the problem, then the depiction is a damn sight more realistic in Doom Eternal (2020) than it was in the original Doom (1993). Each hour of playing Eternal should have a much worse effect on us than an hour of playing the classic.

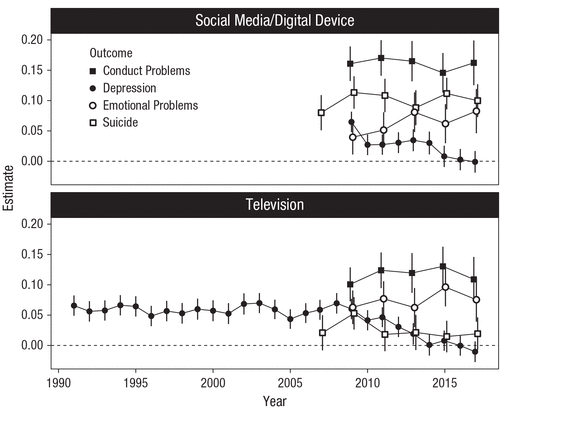

The CPS paper tried to look at that. It looked at three technologies: social media, “digital device use” (so video games or other non-work-related use of screens), and TV. Then it looked at the correlation between the use of those technologies and various mental-health outcomes in adolescents: depression, suicidality, and behavioural and emotional problems. And they looked at whether that correlation has changed over time: is an hour of playing video games in 2018 linked to worse conduct problems than an hour in 2010? Or an hour of TV in 2018 and in 1995?

Bluntly, the answer is no. There is a slight uptick in the link between digital devices/social media and emotional problems, and a decrease in the link with depression, but broadly speaking, there’s no effect:

But, if technology is having the negative effects that we all fear, then this makes no sense! These technologies ought to be getting their claws into us ever more deeply, as they become more finely tuned to capture our attention, as the blood and gore gets more realistic. But it just doesn’t seem to be happening.

This isn’t to say that no one has bad experiences with technology. Obviously some of us do. But it’s a worthy reminder that every generation has its own “video nasties” panic, and as soon as the new one comes along we forget about the last one.

It’s also worth remembering that, right now, we’re going through a process of regulating “online harms”. It is based on the idea that those harms are real. But, as Professor Andrew Przybylski of Oxford University, one of the authors of the paper, said to me: “If we’re doing these interventions, we need to make sure we get good data, otherwise mistakes will be made.” If we’re going to limit people’s rights to use the internet in the ways they want to, then it should be on the basis of good evidence. “It is really shocking and dispiriting,” says Przybylski, “that evidence isn’t at the heart of this.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeOf course we can be worried about the addiction to social media. Much more of concern is the development driven by some media to an inability to stay on-focus and concentrate. This leads to the cry of TL:DR or “that’s a chapter book, too hard”. The trend started long ago with short flashy music videos that begin to demand a shortened focus. The inability to concentrate for sustained periods is an issue facing today’s students.

I agree a sample of one person is not a lot but….

One of my friends was a great reader of books. A few years ago, when he was in his 50s, I asked him what books he had recently read. He replied none and – rightly or wrongly – blamed constant reading on the internet of much shorter pieces as having made him unable to pick up longer things.

I still manage to balance reading a large number of quite long and serious books with consuming a lot of content on YouTube and platforms such as UnHerd. Over the last couple of years I have slipped from about 73 books a year to about 66 books a year. However, this is compensated for by the fact that I am much better informed due to a number of brilliant podcasters who bring me the facts that the MSM will not acknowledge or broadcast, and by the fact that I can access long discussions involving people like Iain McGilchrist, Eric Weinstein, Douglas Murray, Jordan Peterson etc.

So, I would say that the digital world has been a wonderful boon, especially as it allows me to work for clients around the world from my couch. Moreover, I am back on course to read 75 books this year.

Online writing seems to have largely split into two camps. Those where every paragraph is a single sentance and often split up with large pictures e.g Daily Mail; and those where where prolixity, verbosity and bloviation are the order of the day e.g. Quillette.

UnHerd has avoided these traps (so far).

Alternatively, it’s a poor piece of research. It is based on analysing data from questionnaires that asked questions )eg “During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities?”) that don’t meet a clinically recognised definition of anxiety or depression. Academics like Jean Twenge and Jonathan Haidt would take issue with the conclusion and probably ask how one explains the large rise in teen anxiety and depression in the last decade other than by pointing to social media.

It is essential for the continuing employment of MPs to debate, legislate, regulate and ban something that they claim is harmful and demonstrate that they, and they alone, can save us from a terrible harm that we would not recognise without their profound wisdom.

This article seems to be a bit misleading, especially the title. The graphs show that these things do cause negative outcomes. What the research shows is that they don’t change much year by year. It could just be that it doesn’t matter that much about improvements in graphics etc, you are still sitting on your own staring at a screen for extended periods of time.

Perhaps one of the most pernicious results of technology is the way it has changed how we relate to one another. It avoids human contact in which we read mood, tone of language, irony, humour and body language. It replaces it with soulless text and semantic interactions revolving around choice of words (often fired off in a hurry). I’m amazed at how abruptly interactions have degenerated into disrespectful abuse so quickly in the last 10 years. Soul to soul relationships are so important in maintaining our humanity.

Does the “digital world” include artificial intelligence and/or robots? If so, a wider reaching discussion is needed than just that regarding the internet.

Online dating has done a lot to destroy the world of male-female relations.