In the last 50 years Britain has become both more ethnically diverse and more middle class. Since 1972 the ethnic minority population has risen from around 3% to 16% and the proportion of this group in professional-managerial positions has risen from 19% to 50%. But how does social mobility compare between ethnic minorities and the ethnic majority?

According to an analysis I produced for the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, there is an optimistic picture which has, until now, not come into sharp enough focus. The evidence shows that ethnic minorities from professional-managerial families are just as likely to have been socially mobile as their white peers and those from the most disadvantaged unskilled manual origins were less likely to stay put than were their white peers.

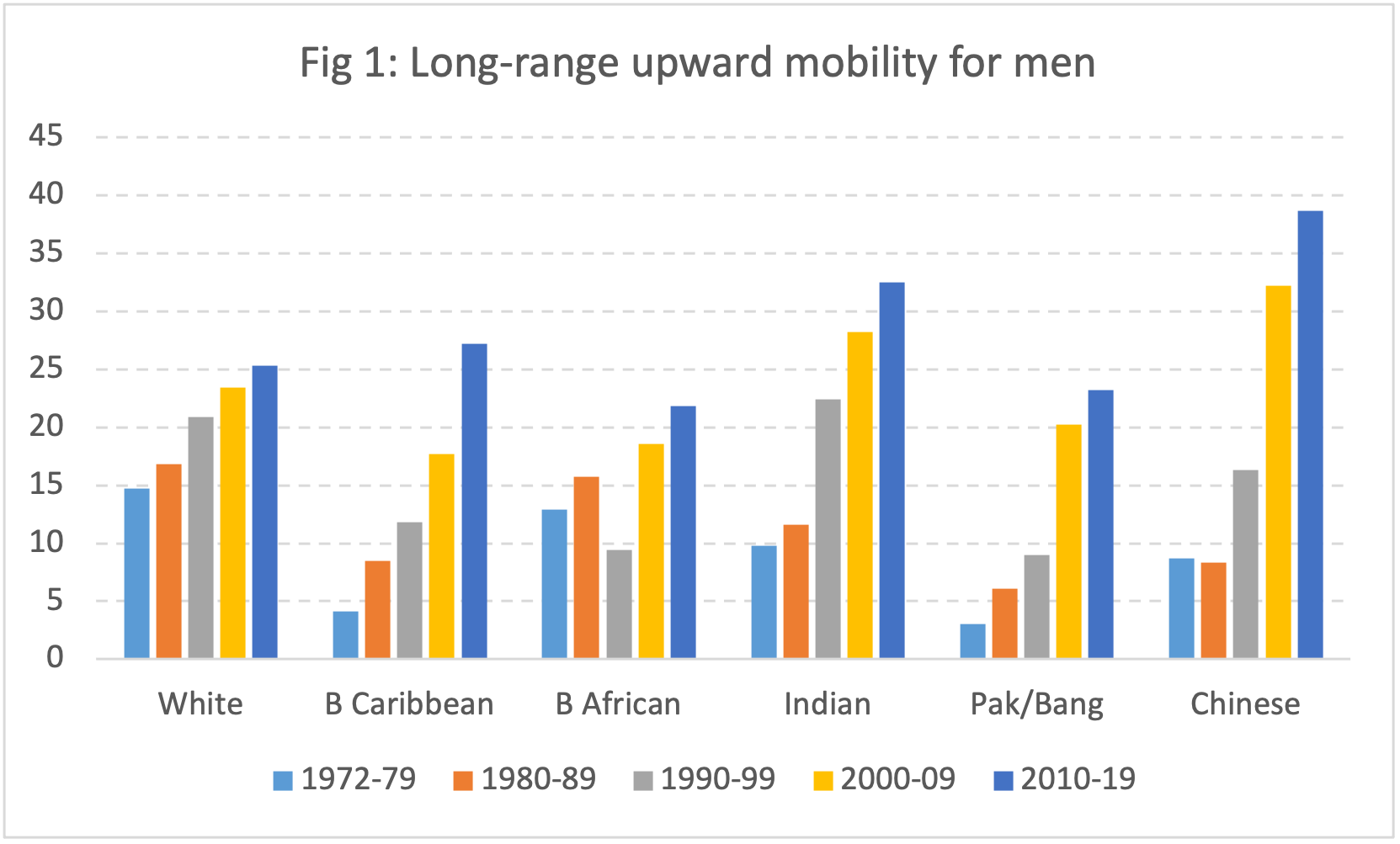

Across the generations there is no uniform ethnic minority disadvantage compared to whites, with particularly impressive progress made by Indian and Chinese groups. Figure 1 shows an example of long-range upward mobility from disadvantaged family origins into professional-managerial destinations. In the first two or three decades, ethnic minority men were lagging behind but in the last decade, they were little different from or were doing much better than their white peers.

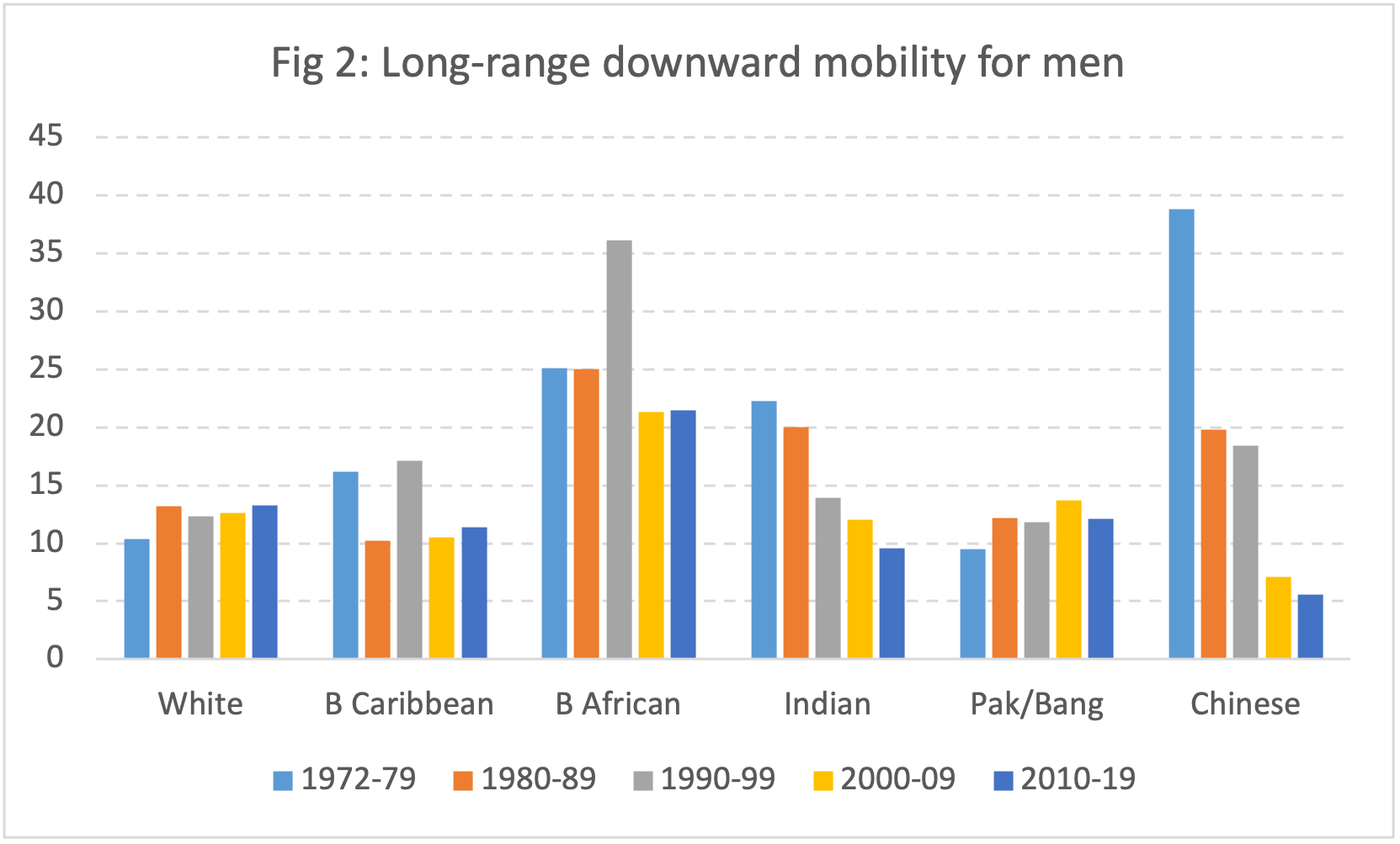

The apparent immigrant drive and aspiration has meant higher rates of long-range upward mobility than long-range downward mobility for Britain’s ethnic minorities over the long term, which can be seen in Figure 2. This country did not see the same blockage on upward mobility as experienced by African-Americans in the US in the 1960s.

In other fields such as education, ethnic minorities actually tend to perform better. For example, access to Russell Group universities by Indians and Chinese immigrants is higher than their white peers. But as figure 3 shows, there is broad progress by all ethnic groups in the last five decades for people aged 25-34. Although black Caribbeans and Pakistanis/Bangladeshis were somewhat behind white people in the earlier decades, they are now catching up, with the latter group having already surpassed them in the last decade. Elsewhere, black Africans, Indians and Chinese in particular are making impressive progress, being well ahead of whites in first or higher degrees. All this data points to a British educational system that is, by and large, a level-playing field.

Ethnic minorities are also advancing into the highest professional-managerial positions. Figure 4 shows that only Pakistanis/Bangladeshis are clearly lagging behind and Black Caribbeans slightly behind. Black Africans have always been doing well although they have fallen behind by a few points in the last decade, probably reflecting changes in immigration patterns. The Indian and Chinese groups are making strong progress in the last two decades and are now well ahead of whites. Overall, for those economically active, career advancement is at a similar level to the white majority.

While it is true that recessions have disproportionately affected ethnic communities, overall Britain has made progress in important areas like education and, to a lesser extent, access to the top jobs. The history of the last 50 years shows that the UK can be a beacon of equality, but it must ensure that this progress carries on at the same rate.

Yaojun Li is a Professor of Sociology at Department of Sociology, School of Social Sciences, Manchester University, with research interests in social mobility, social capital and ethnic integration.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeSo to be completely successful as a multi-cultural beacon of equality the White British have to be driven to the bottom of all the tables. So long as there is an ethnic group below them there is still more to be done.

Here is the brave educationalist Philip Beadle telling it like it is to a roomful of NUT members in 2008 (froma teachers.tv video on the white working-class):

“Difficulties about taking the subject on involve being explicit about race, which can be uncomfortable. You cannot have a properly functioning multicultural educational system when the needs of one social and ethnic group are completely ignored. I’ve sat through whole rafts of assemblies about Nelson Mandela, Rosa Parks, and Jessie Owens, where the only white person mentioned all term is Adolf Hitler. And I’ve watched the white kids squirm with guilt and embarrassment and shame as they are force-fed a daily diet of the doctrine of their own obsolescence.

“How is it possible to reverse generations of ambivalence particularly towards education if they only rarely see images of themselves in school, and most of these are negative?

“Black History Month is controversial among the white working-class – not in that they don’t recognise the right of black people’s celebration of their own culture and history, but the fact that there is no single event through which they may investigate their own culture, and how they come to be here.”

I speak honestly about race, migration, and London, where I left in the 1970s after school to move to USA, and have returned ever since to stay with my parents for visits – so saw London change from 70s to 2019 in strobe like stop motion picutres – of a place I knew completely – but the truth is not allowed. Even here if it is too truthful comments disappear, you must speak correctly.

London now is less than 49% native British, but that is good – right? Because that is the only allowed narrative.

I know what you are speaking of. I lived in the East End from 1997 to the mid-noughties and I have worked in London extensively since and seen the changes. Its so demoralising to see the changes wrought and thousands of years of a culture and history washed away. Its truly awful being asked to celebrate your own demise at the hands of people you let into your home and whose only repayment comes in hatred and bile.

Yep pretty much

‘The history of the last 50 years shows that the UK can be a beacon of equality, but it must ensure that this progress carries on at the same rate.’

Well if the ‘rate of progress continues at the same rate’, whites themselves will be an ethnic minority in the UK. Well they are already across the world if you compare total global populations. For example the number of Han Chinese people I think outnumbers the total number of whites worldwide. I think Mr Lin himself is of Han Chinese descent, the Han Chinese dominate the government and business worlds in China. If Mr Lin was to move there, he would get ‘majority privilege’ in China. As long as he towed the CCP line of course. Someone white or from another ethnic group wouldn’t, in fact they would struggle to get permanent residency. I don’t think the Han Chinese would see it as ‘progress’ to become an ethnic minority in China. In fact their policy is to maintain their majority status.

In terms of being a ‘beacon of equality’ compared to where? China? Where minorities (real minorities like the Uyghurs) are often subject to brutal persecution. It’s a demand for asymmetrical liberalism by people like Mr Lin, who are allowed to push for what they perceive to be their own ethnic interests and use corrupt liberal language. Of course Western states allow this and positively encourage it, (Mr Lin has down work for the UK government). This is due to ideological factors and the business demand for cheap labour.

Precisely. Also due to business demand for an ever-growing consumer base. A consumer base which gains consuming power (money) only if it’s relocated to “Western” welfare states from the ‘global south’ (aka the undeveloping world). Basically it’s wealth-redistribution from worker to corporate business, via the global underclass. Facilitated by the mass-exploitation of Chinese workers producing the consumables in the factories of communist China.

It would be interesting to frame the debate in terms of whether a a majority of the indigenous people at the end of the day can say we have a new group in the country, we are very clearly benefitting from them and we are glad they are here.

I wonder which groups that would be. Each group as far as I can see has quite big defects. Suppose we even took the ethnic group the good Doctor belongs to – one of the less criticised ones.

I will leave others to point out their good points.

Here are ones I would imagine might be their less good points.

Clannish. Running small and often cash-based businesses so less likely to be paying full taxes. Involved in illegal immigration. Have brought organised crime in their wake (Triads). More racist than the average UK person. Employ (exploit?) people on very low wages due to the nature of their businesses, for example restaurants.

And this is, as I say, one of the more praised groups.

It is closer to the truth to say that NO large scale immigration of a group is good for the indigenous people of the host nation – and in fact even quite small numbers can be harmful.

And in fact reading what I wrote again, I have missed out lots of key defects.

Contributing through wealth and purchases to the continued inflated prices of UK, particularly London, property.

Engaged in the illegal drug trade – Fentanyl, for example.

Distorting the UK university system.

Espionage in businesses and universities including military secrets – certainly happening in the US, why assume the UK is exempt?

And this, as I say, an example of relatively good immigration!

I really don’t understand. Why are so many comments SO negative? I really do NOT thing the author is talking quotas or positive discrimination, but shows that if you are motivated enough you move upward.

Would they have preferred to see minorites stagnating or only doing menial jobs?

If there is a problem with (some of) the white population what would they advise, positive discrimination?

Maybe the ‘white’ population needs to ‘haul arse ‘ before automation really kicks in ……….

Maybe we should live sovereign, free and alone in our own ancestral home, without traitor politicians and a hostile corporate and liberal-left overclass.

Nope – just real equality, part of which is no longer being told on a daily basis that its all our fault and we have “white privilege”.

You don’t understand, it doesn’t matter that ethnic minorities are doing well.we already knew they are doing well and better than us.

Whites and Britain is always going to be despised as racist.

No matter what,you clearly need to expose yourself to BAME and their online content.

If the target for ‘access to professional-managerial salariat‘ is, say, 75%, who will do the work? I think we need fewer thinkers and more workers – thinkers just waste time, er, thinking.

Exactly. The number of ‘managers’ i.e. people who don’t do anything, continues to grow. And I don’t know why you describe these people as ‘thinkers’ as I cannot recall a single one of them who is capable of thought.

This is because thought arises from actually carrying out and interacting with the task at hand. The act of ‘doing’ prompts thoughts about why are we doing this and how could it be done better etc.

As one of the ‘doers’ I constantly raise issues and opportunities that have not occurred to any of the ‘project managers’ or ”customer performance executives’* etc because all they do is arrange meetings and make ppts etc. And still organisations and clients continue to pay for so, so many of these ‘people’.

*I kid you not! And the fact is that she is a girl in her early to mid-20s who does literally nothing except look gorgeous in Zoom meetings and, somehow, contrive to rack up hours that the client pays for.

All this levelling up (positive discrimination) based in race, gender, age or any other characteristic rather than ability is a disaster for our country. Here is am example why…..Bob. is part of a politically powerful ethnic group ( union / gender etc or whatever) , so Bob gets a “just wage” as determined by Bob’s relative clout in the political process. Bob’s employer passes on the cost to his customers. But customers aren’t so enamored with the new price ( and perhaps service) and decide to find a new supplier. As a result, Bob’s employer loses market share and 30 people (none of whom are Bob, of course) lose employment. In addition, suppliers to Bob’s employer lose volume and they reduce staff. Bob however is raking in the money. Meanwhile, across the sea, a competitor of Bob’s employer notices the cost increase and seeks exploit the market advantage. (The competitor is hiring btw. But that isn’t the kind of wealth re-distribution envisioned by the state.) Bob’s employer starts to feel the competitive disadvantage and so seeks some market protection from the state. Bob’s labor union thinks that would be a great idea as well. (Bob’s employer also starts looking a production facilities elsewhere but it doesn’t say that out loud.) The state thinks about imposing a tariff to protect Bob’s company but fears a trade war. So it gives a load of money to Bob’s employer. Bob keeps raking in the money. We have re-distributed wealth from the general taxpayer to Bob and Bob thinks it quite just. But was it really? Bob wasn’t overly cognizant of the collateral impacts of his just wage. He just wanted a comfortable living. And he received it.

The most important thing missing here is statistics for white working class. And perhaps class distinctions for other minorities’ classes.

Li,

The foreign populations coerced upon my English people are not our ethnic minorities in any historically normal sense of the term. The fact that the political class labelled them as such decades ago does not make such. The stark reality is that they are imported colonising populations and the clients of a political class which serves not my people but business and other sectional interests.

Naturally, we do not want to live among these populations, and have been fleeing them to settle among our own kind since the whole disaster of mass immigration began. The politicians know this perfectly well, which is why they will not speak honestly about the meaning, for us, of their race project, or let us speak. We are, instead, spat upon and dehumanised for our dissent. The power of the secret state is employed against activists for our life-cause. The police raid their homes. Banks cancel their accounts without notice. Psychiatric cases on the hard left are encouraged to attack them physically in the street when possible, dox them at work, getting them fired if possible. Special hate-words are invented to be thrown at them by the national broadcast and print media, which practise the goebbelesian art of brainwashing the general population on a daily basis.

Meanwhile, our children are propagandised in school, and taught a diet of self-hatred and racial shame. The colonising foreigners are being taught to hate us. Something truly terrible is being prepared for us.

So, please don’t legitimise this gene-killing process by the use of this term ethnic minorities. The Irish are an ethnic minority, arguable Jews; but no others until we, not the politicos, plainly state our acceptance of them.

Yes. The Irish, Scottish, Welsh, Cornish, Jews, Travellers (Irish / Roma Gypsy), the people of various islands, those are the ethnic minorities of the United Kingdom as i know it. (I’m a foreigner.)

NOT the bames.

I find it extremely difficult to believe that black africans outperform white Brits in education, i smell strong cosmetic figures and double standards there. Chinese (Korean, Vietnamese etc.), sure. Indians, quite possibly.

Ditto. I think the first generation of African migrants tend to do better than home-grown “black Britons” because they haven’t quite adopted the victim mentality that pervades some demographics here. But better than white (actual) British? Maybe, but I’m skeptical. East Asians and Indians definitely do on average, I must concur.

This is of course not an argument in favour of greater immigration, it’s like telling red squirrels they’re about to be enriched by the greys, but don’t worry reds, they’re pretty good survivors so why are you worried?

What do you think it’s like being a native brit in the modern educational system? Do you know the term culture shock? Add to that the malignity of the race industry, which owns the teaching profession, and you will be getting close.

Of course, if you really want a flavour of what the establishment thinks of the human worth and meaning of white children, just look at its behaviour over the vast crime of Muslim paedophile trafficking and prostitution of white girls to the wider Muslim male population.

My name notwithstanding (internet, not obliged to use real name), I am in fact a native Englishman. I studied in China for two years without knowing Chinese and I can tell you, I know what culture shock is. My actual opinions on race and teaching are probably illegal in this country – but I am far from alone. That said, the problem with girls in Rotherham was that they had no fathers to look out for them (and yes, discipline them for their unchastity in some cases), they were easy pickings for men who are held to a looser standard (i.e. Pakistanis, Islam is probably more incidental here than in the case of terrorists) – read what they said, these girls were almost never dragged off in tears, kicking and screaming. Quite the opposite. English culture is degenerate and sickening, and cases like Rotherham show the toxic brew of casual sleaze and multicultural invasion we are now faced with.

Good thing you have not used your real name.

“English culture is degenerate and sickening,” really it became so about the same time the great majority stopped going to Church.

What? They were cases of rape and violent coercion into prostitution

Sometimes, yes.

Other times, not so much. Some of these girls were lead into it but the choice was theirs. Others joined enthusiastically but alter regretted it. Some were looking for male attention and got more than they bargained for, some were deceived, some signed up because they were drawn to these strong, dangerous types. My point, wilful single motherhood is a scourge, and one problem brought on by it is that the children of such unions have no father-protector, in addition to have no sense of propriety or moral boundaries in regards to adult men (having never been in a loving and non-sexual relationship with an older male, who would in any sane society be their own father). I am often appalled reading accounts of mothers who were trying to lead their daughters out of this behaviour (where not just allowing it), they were incapable of actually stopping their trollop daughters from just going of and doing what they wanted to do, often getting seriously hurt in the process. And yes, some teenage girls can very much be trollops.

From what I can see children of any ethnic background who are supported and encouraged by their parents and are sufficiently self motivated to learn do well in education. Those who are not, do not. The incentives to improve yourself and give your children a better start than you had are there for all ethnicities but particularly for non whites – why did the original immigrants immigrate in the first place if it was not to gain a better life for themselves and their children and grandchildren? Sadly there is a growing rump in the indigenous community that thinks the state should look after them and they don’t need to bother. With this in play in the statistics, the results are hardly that surprising.

What’s the point,even when ethnic minorities do better than whites- they will still hate us and call us racist and call this country racist.its exhausting, on social media they are constantly expressing their contempt.Whilst they are personally in a good socio-economic position and much of the country’s most deprived socio-economic locations are predominantly white.

How can you talk about disparities between different ethnic groups without even once mentioning IQ?

IQ is overrated. Effort rewards more.

Interesting assertion. And your proof is…..?

Conversely there is no proof that IQ is an absolute measure of intelligence.

Nobody says it’s an absolute measure. It’s an adequate measure, not an absolute one.

IQ has been clearly shown to be the same across the human species because the brain has not had time to change much since we left Africa-however one’s brain can increase IQ by 20 % by sheer hard thinking work and practice – which is more the norm in some cultures than others _ just do some IQ googling and avoid the idiots who have not done much of that thinking !

That’s wildly incorrect.

Pardon? No it has not. This is absolutely false, it has been demonstrated to vary wildly across the planet with significant standard deviations across continents – see sub-Saharan Africa vs East Asian average IQs. Even poor countries like Vietnam’s grossly outperform stable African nations, and by far.

Should I also avoid idiots who claim that IQ is same across the ‘human species’ which is clearly cobblers?

height is also the same across nations, it is all diet which makes it seem not so. (extrapolating from his IQ argument.)

Plus environmental norms eg “you WILL do well at school young man/woman (or there will be trouble !) – er kind of like real leadership from parents vs “just follow what your clearly intelligent peer group tells you “.

Effort is overrated, rather. Achieving the same result effortlessly / with lesser effort is more rewarding than exerting more effort. And that’s where IQ comes into the picture.

Pakbang, i like that word. Will take it. Should be a good mileage in it before it gets added to the censorfilter algorithms.

It even works as a verb, pakbanging, pakbanged – “thousands of English and Sikh girls were pakbanged in English towns with the authorities’ implicit consent“, etc. Good word. Thanks.

My wife is a teacher. When children, newly arrived from abroad and new to the school are asked to write down who their heroes are, they tend to write down scientists, like Einstein, statesmen like Mandela or artists like Leonardo da vinci. English kids write down footballers and Celebs. This is a state school, the teachers do their best, but we are failing to engage these young people, offering the possiblity of something beyond the limitations of their circumstances.

Too often amongst my educated friends, I sense a fear and contempt for a white working class, that used to be seen as a bulwark against political excess. Now they envy the comfort they feel in their own identity while simultaneously despising them as parochial and unschooled. The cosmopolitan graduate class seem to loathe this country, having wrung every early opportunity that they can, out of it. In their hands I can’t for the moment see any improvement in the prospects of young white working class kids.They probably wouldn’t welcome the competition, that they would present. I realise I was so lucky to come through the sixties and seventies with a state education, supported into further education by both Labour and Conservative governments.