Lady Ottoline Morrell with Theodore Powys. Credit: National Portrait Gallery

A secluded Dorset village might seem an improbable gathering point for avant-garde writers and artists, Bloomsbury grandees, sections of the London smart set and an unusual Cambridge philosopher. But that is what the parish of Chaldon Herring (otherwise known as East Chaldon) became in the 1920s and 1930s, after the writer Theodore Powys settled there some twenty years earlier. One of his brothers, Llewelyn, moved there in the mid-twenties; the other, John Cowper Powys, arrived periodically from his lucrative American lecture tours dispensing gifts. Between them, the three Powys brothers attracted many who were distinguished cultural figures in their own right.

The musicologist, poet and novelist Sylvia Townsend Warner — author of that tale of modern witchcraft and female rebellion, Lolly Willowes (1926) — met her lifetime companion, the poet Valentine Ackland, in Theodore’s home. They are buried together in the graveyard of the village church, St Nicholas. The writer and publisher David Garnett, author of the Kafka-like novella Lady into Fox (1922), which tells of a newly married young woman transformed suddenly into a fox, was a frequent visitor to the village. The society hostess and patron of the arts Lady Ottoline Morrell, who helped arrange financial support for Theodore when he faced poverty, swept in from time to time.

Around eight miles from Dorchester and not on any beaten path, the village was a strangely numinous place when I used to visit it some years ago. Alone in the church, I found a single page torn from Theodore’s short story collection Fables (1929) lying on the ground, which I picked up and left on a battered wooden table at the entrance. On another visit I noticed an old-fashioned telephone box that seemed misted up. On opening the door I discovered the interior was completely festooned with cobwebs. I’d have liked to have known if the phone was still working, but that would have meant stretching out my hand and possibly damaging the spiders’ work. So I closed the door and left the webs intact.

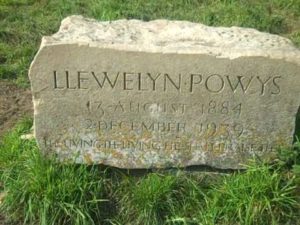

Later, struggling up a precipitous path leading to the sea, I located a memorial stone dedicated to Llewelyn hidden in long grass not far from the cliffs. This was after several failed attempts to find it on earlier visits. Along the way I would pass Chydyok, the brick and flint cottage where he lived with his wife, the American suffragist and writer Alyse Gregory. In order to be with Llewelyn in this remote place, she had given up the editorship of The Dial, a magazine based in New York. She had written on Katherine Mansfield, Marcel Proust and Paul Valéry, among other contemporary authors, and commissioned many notable reviews, including one by T. S. Eliot of James Joyce’s Ulysses. Living there was not easy for her. For some years Llewelyn carried on an affair with the poet Gamel Woolsey, who lived in the nearby seaside village of Ringstead with her partner Gerald Brenan, who became author of The Spanish Labyrinth (1943), a study of the events leading up to the country’s civil war. Like Llewelyn, Gamel suffered from tuberculosis.

When I was slowly picking my way up the steep path, I often recalled a story told me by the philosopher Michael Oakeshott, of how he visited Llewelyn when he was living in a shelter set up for him in the garden. Lying on a bed, Llewelyn pushed a book toward him and whispered, “Read to me about the Kingdom of the Fairies”. The book was Leviathan, in which Hobbes attacks the Catholic Church as “a kingdom of darkness” and compares it with the fictional realm of the fairies. Oakeshott, who records the episode in his Notebooks 1922-1986 (2014), read to the seemingly dying man “until the sun went down”.

Llewelyn returned from the brink of death at many points in his adult years; he eventually died in Switzerland in 1939, aged 55. His life-long closeness to death was one of the chief inspirations of his personal philosophy: an impassioned, life-exalting atheism. The other was his devotion to sexual pleasure, for which he repeatedly risked reinfection in erotic encounters, in the sanatoria where he recuperated whenever his illness worsened. Despite having contemplated joining the priesthood in his youth and remaining respectful of religion throughout his life, the Cambridge philosopher seems to have had an instinctive sympathy with the frail libertine unbeliever.

Oakeshott’s interest in the Powys family extended to John Cowper, whose book The Meaning of Culture (1929) he reviewed, and Theodore, whom he remembered consuming vast quantities of gin in the local pub, The Sailor’s Return. Oakeshott shared John Cowper’s view that “the essence of culture is the conscious awareness of existence”, and for both of them that included a full consciousness of human mortality. Interestingly, the book of Theodore Powys’s that Oakeshott mentioned to me most often was the novel Unclay (1931), in which Mr. John Death comes to the village of Dodder to “unclay” two of its inhabitants, loses the parchment on which their names are inscribed and falls in love with one of them.

The meeting place of three brothers, Chaldon Herring was home to three philosophies. Each of them took as a given the passing of Christianity. But whereas Llewelyn welcomed the decline of religion, Theodore — even though he had no trace of belief in him — thought it the only subject that mattered. His best known novel, Mr Weston’s Good Wine (1927), tells of an old man in an overcoat and brown felt hat who arrives in the village of Folly Down in a mud-spattered van to sell two wines — the light white wine of love and the dark wine of death. Time stops, and the old man disburses his wares throughout the village. At the end of his visit he instructs his assistant Michael drive him to the top of Folly Down Hill, and drop a burning match in the tank of the van. The two of them — God and his angel — then vanish in the smoke.

A later novella, The Only Penitent (1931), has a country vicar forgiving a mad old man called Tinker Jar — another avatar of God — for creating the world, and granting him the supreme gift of everlasting nonbeing. Far more subversive of established pieties than anything in the canon of conventional atheism, Theodore’s tales of a Deity yearning for its own annihilation are among the most beautiful allegories in English literature.

The third of the brothers was the most elusive. In his Autobiography (1934), he describes himself as a follower of Pyrrho of Elis, the ancient Greek philosopher reputed to have founded scepticism. John Cowper Powys cherished religion as an aesthetic phenomenon, not a system of belief. He kept open the possibility that something of him might survive death, only to renounce any such hope when he heard that his beloved Llewelyn had died. In later years (born in 1872, he lived until 1963) he wrote that he was happy death would be the final end for him. His greatest novel, Wolf Solent (1929) shows the central protagonist struggling to live as Powys himself tried to do: enjoying the fleeting sensations of life while enduring the sorrows it also brings.

Chaldon Herring in the interwar years was not only an unlikely gathering place for some of the brightest cultural figures of the time. Even more improbably, it was the scene of one of the most interesting twentieth century attempts to fashion a philosophy for people who no longer imagine any transcendental order. The avant-garde that flocked to the village may not have grasped this fact, and yet it may have been what drew them there. It remains extraordinary that some of the most radical experiments in post-theistic thinking should have been explored not in an ultra-modern metropolis or provincial city, but a village folded in a valley in deepest Dorset.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeChaldon is not 80 miles from Dorchester but just over 8. The Sailor’s Return was a legendary ‘locals’ pub, especially during the 70s (when it was my local) and filled with true Dorset characters and eccentrics. Food was a bag of crisps or a sandwich or, when Dotty opened up her immaculate dining room, full roast dinner and sometimes rook pie. But you had to take your shoes off to keep the carpet clean! You were served from a hole-in-the-wall at the end of a narrow corridor and the flagstoned public bar was on your right-hand side, with scrubbed wooden tables and benches. Both the gents and the ladies were outside and in pitch dark, unfathomably scary – well at least for us ladies.There used to be a plaque in the window seat commemorating Roy, a local farmhand, who sat there every night of his long (adult) life, drinking and carousing. If he came into the pub and there was a ‘foreigner’ sitting in his seat (locals knew better) he or she would be summarily ejected to allow Roy to settle his considerable bulk into ‘his’ seat to commence imbibing. It was a magical place, a tiny thatched cottage/pub perched on top of a hill overlooking the fields, the church and part of the village. When we returned to Dorset in 2011, the Sailors had changed almost beyond recognition. Much extended and enlarged – and with smart, indoor toilets! – it is much more geared to tourists and those who want to eat. It’s still a lovely place to go, with great food, but the spit and sawdust rural charm has gone, along with much of the magic. So has Roy’s plaque, which has been removed from the window seat and replaced by a smart new one, on the outside wall of the pub, commemorating Llewelyn Powys.

What a beautiful story. In my life I have known pubs like that.

‘The society hostess and patron of the arts Lady Ottoline Morrell…. swept in from time to time.’

Now there’s a surprise.

For cultural historians the century between 1860 and 1950 was “the age of cultural despair”, the Somme, The Wasteland, Auschwitz & Hiroshima. God disappeared, until improbably, Heidegger, wandering his forest paths, found him again.

“It remains extraordinary that some of the most radical experiments in post-theistic thinking should have been explored not in an ultra-modern metropolis or provincial city, but a village folded in a valley in deepest Dorset.”

If you go back through history – not just UK, but anywhere in the Cro-Magnon settled world, you occasionally find that groups of “intellectuals” who have attempted to fashion a utopian social/cultural/economic order of some type. Usually they have to create their own village or assume control over an existing village, in order to make their philosophy manifest. This is usually because the modern metropolis they are fleeing has been operating under the chimerical structure they have just devised, for the past century or two.

To wit, the Plymouth/Boston/New Haven refugee colonies? East Chaldon, by contrast, seems less new paradigm-ish, than effete dolce vita, no?

Interesting that the village is described as being 80 miles from Dorchester. A quick look at Google Maps shows it to be a mere 9 to 12 miles (are miles still in use in the UK?) Not really important, but just thought it was worth mentioning. It’s almost a suburb of Dorchester, hehe…

Perhaps he meant 80 miles from The Dorchester, which is the sort of place where these people would have had high tea and high jinks.

Hehe, just possibly so 🙂

Thanks for this – I’ve been there – to the old pub on a dark Autumn night, long ago. Didn’t know any of this history

Infinite space as one plane of existence (godless) or infinite space conceived as multiple planes of existence in the form of holarchical concentric circles (god). I imagine a village is a perfect place to contemplate either and to also contemplate what we are, where we are, when we are, how we are and why we are.

ðŸµï¸ðŸ’®ðŸŒº

In Brideshead Revisited, Charles, after having read Sebastian’s correpondence, peruses a copy of Lady Into Fox whilst waiting for Sebastian in his rooms.

Sebastian is portrayed almost as a child of nature at that stage, to whom art and literature are superfluous, yet it seems he is reading Kafkaesque literature all the while!

Or perhaps it was a fashionable novella of the time, and is supposed to be an indication of frivolity – Sebastian should have been studying texts for his degree! It would have been recently published. One wonders whether he would even have read Lady Into Fox himself, so disdainful of learning is he portrayed! I haven’t read it either!

There is a disastrous fox hunt in BR. Sebastian is perhaps Sylvia and Charles Richard?

‘Wolf Solent’ is a good read, but John Cowper Powys’s greatest novel must surely be ‘A Glastonbury Romance’. I was introduced to it at school and have reread it many times since.