Will the kids be alright? Credit: Christopher Furlong - WPA Pool/Getty Images

Something unusual is happening among Britain’s youngest voters, known as Generation Z or the Zoomers. Increasingly, those under the age of 22 seem to be diverging from voters aged between 22 and 39, and appear considerably more conservative, to the point where today’s 18-year-olds are about as right-wing as 40 year-olds.

How might this be explained? Are Zoomers just more irreverent, reacting against their politically-correct older siblings? Or is it that Britain’s newest voters are simply too young to have been shaped by the Brexit shock? Whatever the explanation, in the immediate post-Brexit years the youngest voters were 40 points more liberal than the oldest. Today they are only 20 points more to the Left.

The rise of Right-wing populism in the West from 2014 onwards led some to argue that the future heralded a nationalist revolt against the multiculturalism of the post-1960s era. The staggering demise of mainstream Left parties in recent years is attributed to their pivot away from economic issues toward an embrace of globalisation and a concern with the claims of disadvantaged racial and sexual minorities, and other identity politics issues.

Against this is the theory, found both in conservative analyses like Ed West’s recent book Small Men on the Wrong Side of History, and liberal ones like Pippa Norris and Ron Inglehart’s Cultural Backlash, that young people are trending ever more Left. Less attached to tradition and more physically secure, they are embracing empathy and liberalising social change, and each new generation is more liberal than the last. Those who vote for anti-immigration parties like Ukip in Britain or the AfD in Germany tend to be older, and, as they die off, western societies will begin electing the Left once again.

The former theory suggests that Left parties need to shelve their wokeness and liberal immigration policies to avoid repelling disadvantaged whites. The latter counsels patience: history is on the Left’s side, and, with generational turnover, demography will carry it to victory. On this score, Biden’s strong poll numbers might be a harbinger of Left-liberal resurgence.

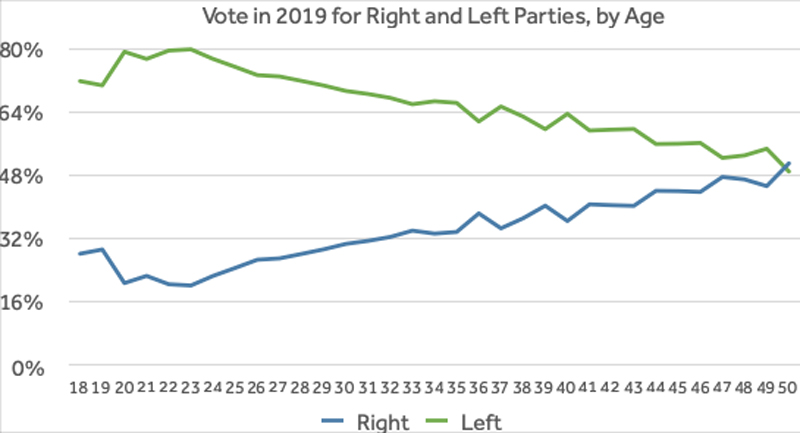

This certainly seemed to be the case in Britain, where, at the December 2019 election, the Tories won just 21% of the 18-24 age group but 67% of those 70 or above, so that age seemed to have replaced class as the primary cleavage of British politics. What seems to have occurred, starting slowly in the early 2000s, and gathering pace after 2010, very much fits his argument that newer generations, moulded in a progressive mediascape and education system, are set to enact “the biggest cultural shift in half a millennium”.

Figure 1, which I have compiled from waves of the British Election Study (BES) going back to 1964, shows little difference in the voting patterns of those under 25 and over 65 up until 2001. However, beginning with the 2005 vote, a six-point gap opened up between young and old, steadily widening until it reached 40 points in 2017 and again 2019. In the last election, according to the BES, nearly eight in ten young people voted for Labour, the Liberal Democrats, Greens or Left-inclined regional nationalists.

Young people really seem to inhabit a different world to the old, and it is about culture. Most of the age gap doesn’t concern economic redistribution, where Millennials tend, if anything to lean toward individualism and away from redistribution. Rather it revolves around “culture wars” questions, notably immigration, attitudes to race, gender and sexuality, as well as Brexit. Millennials are simply less attuned to British traditions of nationhood and more influenced by the liberal cosmopolitan ethos of film, vloggers, pop music, advertisers and the education system.

Figure 1.

The story of the never-ending march of each generation toward liberalism is difficult to square, however, with Gen-Z’s more conservative tilt. If the youngest voters are now moving in a conservative direction, much of the empirical ground under the West-Norris liberalisation claim collapses.

In the earliest stages of a new trend, it is often difficult to acquire sufficient data to rule out statistical blips — but the growing conservatism of the youngest British voters can no longer be readily dismissed. YouGov maintains what is arguably the largest panel of survey respondents in the western world, its Profiles dataset containing the views of over 200,000 people.

This means that for every single age (apart from the very old), there are some 3,000-4,500 people — a much larger sample than one finds for all age groups in most opinion surveys that make the news. So we can’t dismiss trends at the youngest edge of the age graph as a statistical aberration.

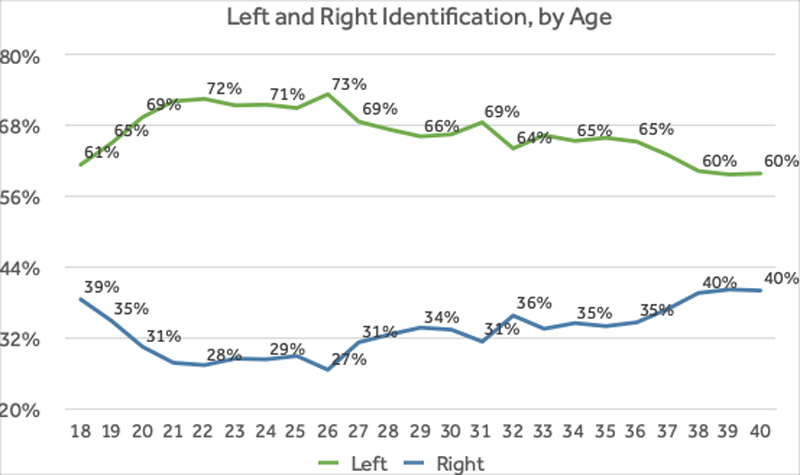

One YouGov question asks “Some people talk about ‘Left’, ‘Right’ and ‘centre’ to describe parties and politicians. With this in mind, where would you place yourself on this scale?” The scale is a 7-point question from “very Left-wing” through to “very Right-wing”. The share of those who don’t know where to place themselves is about 30-40 percent between age 18 and 40, with no clear relationship to age. If we remove those in the centre — where it is also difficult to discern an age pattern — and amalgamate all shades of left and right into two categories, this yields the graph in figure 2. (Coda for those sticklers out there: if we don’t remove centrists or those who don’t know, but instead compile everything into an index of all data, the results remain the same.)

What is striking is that the views of today’s 18-year-olds are basically aligned with those of 40-year-olds. If young people were trending consistently more liberal over time, the biggest gap between the two lines should be at age 18, but instead it is between 22 to 26, where there is a 40-point gap between Left and Right.

Figure 2.

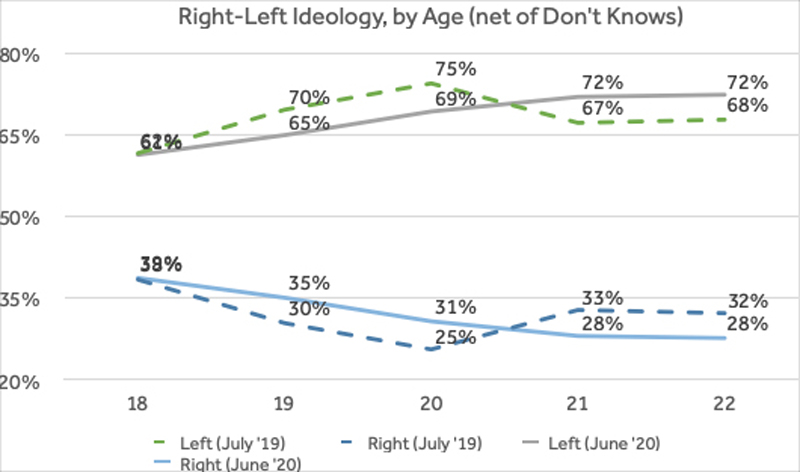

These trends seem to be ongoing. Profiles data (at least that which I have been able to see) begin in July 2019, and Figure 3 compares data from a year ago with data from now. There is always some variability in a sample, but if you look at the same question a year ago, what you find is that the most liberal age was 20. Now it is 21 or 22. This is consistent with the pattern of a more Left-wing Millennial generation moving through the electorate as it ages while a more conservative Zoomer generation takes its place.

Figure 3.

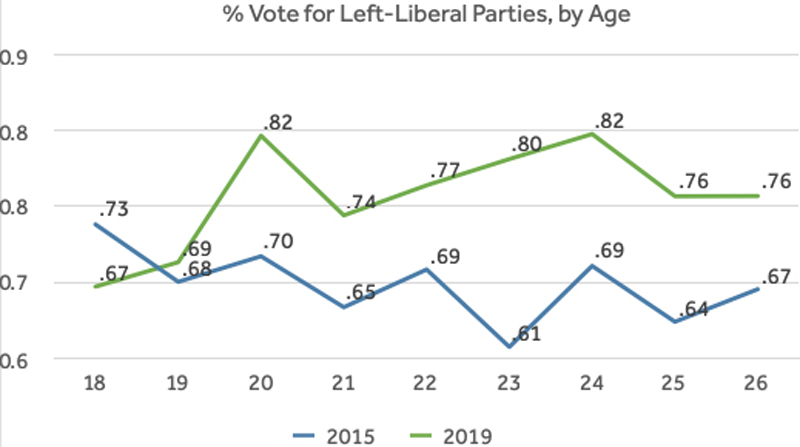

Weren’t 21-year-olds always more Left-wing than 18-year-olds? After all, the younger group haven’t attended university. Actually, no. The British Election Study allows us to go further back to see how things have changed since Brexit. In 2015, the BES age-voting series showed the classic West-Norris cohort liberalisation pattern of Left-identification and voting rising monotonically with age. Eighteen-year-olds were most Left-leaning. That is no longer true.

Why is this? Could it be that today’s 18-year-olds have yet to go through the liberalising crucible of university education, and when they do, they will be as liberal as today’s 22-year-olds? In a word, no. For one thing, the evidence that university has much effect on the political attitudes of students is pretty thin. For another, whether we look at men or women, students or non-students, in YouGov Profiles, the 18-year-olds seem more conservative than the 22-year-olds.

Further evidence comes from the BES. Unlike Profiles, whose data I can’t access for multivariate analysis (even the little I have shown is only permitted due to me purchasing an expensive survey), the BES allows me to screen out the effect of university attendance, gender and even attitudes to immigration and redistribution. Its latest wave asks people who they voted for in 2015 and 2019, so that assuming a 22-year-old in the 2019 data was 18 at the time of the 2015 election, this allows us to compare voters of the same age during both contests.

BES is a smaller sample than Profiles so the data are bumpier, but the basic trends are the same, and what the numbers reveal is twofold. First, in 2019, with the exception of a bump at age 20 which could well be noise coming from a smaller sample, support for the Left peaks at age 24, with 18-year-olds considerably less likely to vote for a socialist or liberal party. By contrast, in 2015, the line — with bumps for smaller sample size — slopes downward Left-to-Right: the younger the voter, the greater their chance of voting for a Left party.

Figure 4.

So what explains the Zoomers’ relative conservatism? While I can’t test this systematically because I don’t have the Profiles dataset, I have been able to look at patterns in the figures, and I believe there are two leading explanations. The first, which I consider more likely, is the fading of the Brexit shock. The second, revolving around Zoomers’ hostility to political correctness, receives weaker support.

After Brexit, Millennial voters shifted strongly against the Conservatives. The typical 23-year-old in 2019 had, controlling for gender and education level, an 80% chance of saying they voted Labour, Lib Dem, Green or for a regional nationalist party. But the same voters, aged 19 in 2015, reported just a 68% chance of having voted for a Left party. So young people moved against the Tories between the 2015 and 2019 elections. On the other hand, the 18- and 19-year-old voters of 2019, just 15 and 16 at the time of the Brexit result, hadn’t reached political maturity. Having missed the anti-Tory bump of Brexit, their voting patterns recall those of the pre-Brexit Millennials.

Is there any evidence for a “Jordan Peterson effect” of Zoomers rejecting the Left-liberalism of their older siblings? This would truly be the death-knell for the “coming left majority” thesis. One US survey finds Gen-Z to be more politically polarised, and, especially among men, less politically correct — influenced by countercultural voices on social media rather than the mainstream media and educational institutions. On the other hand, Pew finds American Zoomers to resemble Millennials. This said, firm conclusions are tricky because some of these surveys sample children as young as 13, before they have reached political maturity.

While the fading Brexit shock seems to explain Zoomer’s reduced leftism, this may not be the whole story. For example, in the BES data, which admittedly suffers from a smaller sample, a typical 18-year-old in 2015 — before the Brexit shock — had a 73% chance of voting for a Left party, whereas an 18 year-old in 2019 had only a 67% chance of doing so. This indicates a move to the Right despite Brexit, and that something else might be going on.

Attitudes to immigration or the economy in Profiles don’t appear to differ much between Zoomers and Millennials, so this is unlikely to explain the conservative drift among youth. On the other hand, support for political correctness (net of opposition to it) is 5-10 points lower among 18- and 19 year-olds compared to those aged 22-29. This seems to be especially marked among 18-19 year-old men, who are 10-15 points more opposed to PC than in favour of it — even as Zoomer women are 30-40 points more in favour of it than against it. This gender divide may become a critical one for the politics of Gen-Z.

Political correctness is generally a bigger issue for young people compared to the old. But even so, it’s noteworthy that in Profiles, 20% of 18 and 19-year-olds, the highest of any age, say political correctness is a top issue. This compares to around 13-14% of those aged 22-29 who say it is important. Despite this, there is bumpiness across age groups and results shift somewhat over time, so I am not convinced this relationship is as strong as the Brexit one, and the data seem to fit the story of a Brexit shock better than that of an anti-PC backlash.

West’s argument, like Norris and Inglehart’s, is that younger generations are becoming ever more liberal and will usher in a revolutionary change as the electorate ages. That story is yet to be written, but even though Zoomers appear more Right-leaning than Millennials, we’ll need to see evidence of further change before we can dismiss West’s thesis.

In the 2019 election 18- and 19-year-olds were about 10 points more likely to vote Conservative than those aged 22-30. There is a similar pattern for party identification, with 18-year-olds about ten points more likely to identify with the Conservatives than 22 year-olds. Nevertheless, the distance the Tories still need to travel among Zoomers is great.

Figure 5.

James Tilley, using data that tracked voters over a 30-year period, showed that people become 20 points more likely to vote Tory between the ages of 20 and 80. If this holds, today’s Zoomers will still be only 50% Right-leaning when they reach their ninth decade, and long before this the hyper-liberal Millennials will have worked their way through the electorate, causing elections to swing far to the Left before moving back toward the centre.

All told, Zoomer conservatism is currently not strong enough to alter the broad picture West paints. Only time will tell if younger members of Gen-Z drift even further Right, but it’s probably safer to assume otherwise. The Conservatives are going to have to do a lot more to reverse the leftward drift of the culture if they hope to remain competitive in a generation’s time. As things currently stand, they do appear on the wrong side of history.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeThe young have a natural tendency to rebel against the orthodoxy; always have. Little wonder the crushing conformity of the dominant, enforced, PC culture is now the target of that rebellion. I have young adult children (27, 30 and 32), they are quite conservative, decidedly right wing, and even as school age kids they and their friends would describe something false, ineffective and pretentious as “gay” and more latterly as “feminist”. They aren’t anti those things just their “look at me” pretensions. I thought it was delightfully irreverent.

The under thirties rarely watch or read mainstream media and it’s great that they have the opportunity to hear the likes of Jordan Peterson, unfiltered by the cultural overlords. They’re not stupid and can instinctively recognise authenticity in a world that’s anything but.

“More power to them” as the great man himself would say.

The young rebel. And particularly men whom in my experience are more comfortable adopting positions which place themselves outside of polite society (including apolitical stuff too).

Im slightly older than your kids but my entire peer group (lower middle to middle class but have now got solid enough careers and mostly own a house) is fairly socially liberal but very opposed to the activist led modern left. Not natural conservatives on the whole, but currently their voting patterns are dictated primarily by opposition to the emergent and oppressive orthodoxy. If Starmer plays his cards right then they’ll stay swing voters I reckon, but if not then I think they’ll become lifelong tories without realising it in their mid to mid-late 30s

Thanks Chris, my lot have done OK, all happily married, all have their own houses and businesses (2) or responsible jobs and a good wee crop of beautiful grand-kids for pops to dote over. Fortunately they were bright enough to not need to go to university. My son’s wife did (she’s English, we’re Kiwis) and she’s quite decidedly left leaning while her parents are definitely not. Perhaps the indoctrination at varsity is responsible.

‘As things currently stand, they do appear on the wrong side of history.’

For a party that’s been ‘on the wrong side of history’ since about 1850, the Tories have spent a long time in power. I don’t have much to do with young people but my god son (who is very smart and studies PPE or some such at KCL) see through all the leftie nonsense. Meanwhile, I think that even those with little knowledge of political or economic history know that whenever the left is in power the result is economic collapse and, quite often, the death of millions.

Spot on…look at how well the right have done, in terms of covid-19 deaths, in USA, Brazil and UK.

And Spain Italy and Sweden are left-leaning governments…

It’s probably more complicated than a left-right debate

Thank you all, some examples, from both sides of the fence, and some in between! Much better than sweeping statements I find.

I am referring to the deaths in gulags and killing fields etc, not trough Covid-19. That said, it is not unreasonable to compare the nursing homes in New York (run by a left wing governor and mayor) and the UK (run by a theoretically right wing but actually rather left wing) government to killing fields.

He knew that, but was obviously trying to be facetious – that’s all the left have in their depleted armoury – the evidence over more than a century belies their moans and cavils.

An alternative reason for the apparent change is not that the political views of the young have changed but that the views of the UK political parties have changed..

Arguably Labour have gone harder left, showing some unpleasant authoritarian behaviours and poor leadership, but the Conservatives have started moving into the ‘centre’ previously claimed by Labour.

Similarly the failure of the Red Wall may have been triggered by Brexit but it may also have been traditional Labour voters realising that Labour no longer support the social conservatism of their ‘class’.

So the alternative argument is that English voters are still socially conservative and the Conservatives appeal more on this basis, whatever the demographics. The test will be if the Millennials also start voting ‘Not Labour’.

I agree. Mostly. The article focuses on the movements of the electorate but the key factor may be the movement of the parties and not of the individual groupings within the electorate.

Not coincidence that the two elections where Labour received a drubbing were those where they had moved markedly to the left; 1983 and last year. Although these defeats involved looney manifestos -ref. Labour’s ‘longest suicide note in history’, poor leadership with both Foot and Corbyn being dire we have to understand that the left not the centre nor even centre left is Labour’s natural home. When Labour moved to the centre under Blair they governed for 13 years, although helped by poor leadership this time by the Tories.

I doubt that much has changed in terms of positioning dynamics. Whichever party dominates the centre gets to govern.

In macro terms two factors seem important in determining who will win the next couple of elections. The first is the competence of the current Tory government during steady state. Which it has yet to have. And of course allied to that is what the government is ‘for’ when Brexit and Covid are astern of us. We have yet to find that out. And the second is Labour’s appetite for power. Are they content to be true to their principles which means in reality occupying the opposition benches or will they flex ie compromise those principles, revive a New Labour approach and target the middle.

Should be an interesting few years.

An interesting article thank you. For me the most concerning statistic was the disparity between young men and women highlighted by the author. The popularity of the excellent Jordan Peterson has shone a light on the level of discontent with the Woke leviathan by young men in particular. It would seem likely that this divergence in political leanings between the genders may be exacerbated once they go to university where the fires of suppression of free speech burn brightest. I can only hope that the principles of success through self-responsibility espoused by JP prevail over the more obvious temptation to blame one’s ills on the opposite sex.

At last, an admission that “the evidence that university has much effect on the political attitudes of students is pretty thin”. The truth is that students bring these values to campus, and, because we’ve adopted a model in which students are treated as “customers” and academics are “service providers”, everyone feels obliged to fall in line with their demands.

The catastrophe that has undermined university education in this country was the introduction and drastic increase in tuition fees, which created this market-oriented mindset in the first place. When I was an undergraduate in the late 1990s (the last year group that received a small government grant), it would never have occurred to me to think that I had any right to challenge the political views of my lecturers, or to demand that the university implement my ideological priorities; it wouldn’t even have occurred to me to challenge a disappointing grade.

The sudden swell of radical politics on campus came in the wake of the decision to put tuition fees up to £9,000, a decision that triggered a visible change in attitudes and behaviour. This was shortly followed by the moment when the generation nurtured on social media arrived at universities with a set of ready-made attitudes forged in an environment tailor-made for zealotry.

If the present cohort of 18-year-olds really are more moderate, it will be interesting to see what effect this has on universities as they move through the system. Perhaps some of the enthusiasms of the last four or five years will be jettisoned as quickly as they came.

it would never have occurred to me to think that I had any right to challenge the political views of my lecturers

I was at the LSE mid 70’s-most of my lecturers would have been profoundly disappointed if I hadn’t challenged them-they were always spoiling for a debate-as was I-marvellous times.

Yes, but you wouldn’t have reported them and petitioned for them to lose their jobs, probably, if they dared to disagree with you. Colleges these days are scared of standing up to students because they bring huge revenues with them. In a weird way Higher Education is the intersection where communism and capitalism cozy up to each other.

“In a weird way Higher Education is the intersection where communism and capitalism cozy up to each other.” I have had thoughts along similar lines myself. Again, this will go on until tuition fees are abolished and students can stop thinking of themselves as customers.

Oh gosh – but that’s different. My phrasing was misleading, I realise. I might well have argued politics with my lecturers. What I wouldn’t have done is assumed that a political difference undermined their lecturing abilities or the right to hold a lecturing post!

Sadly, “mine angry and defrauded young” comes to mind here.

A sense of ludicrous entitlement, worthless degrees, and unrealistic aspirations, will leave the “present cohort of 18-years olds” profoundly disappointed, and very, very, upset!

If only for the days of Porterhouse Blue, “to live and die in Porterhouse”.

Dives in omnia!

I gave my two teenage sons, both now in their late 20’s, the advice that they should get the best grades at A level and the best degree from the best university. I pointed out to them that unless they decided on a technical career the degree merely showed an ability to accumulate knowledge which would open the right doors.

They both achieved excellent degrees from top universities ( Byzantine history). One joined the RAF as a trainee the other became a delivery driver.

My advice must have come to them after a few years of reality. They now both work for the government and avoid telling me anything by quoting the Official Secrets Act. They’ve both worked hard and have good prospects but cannot see any possibility of acquiring any property; not at least until my demise.

They haven’t reached the upset stage yet but I have profound sympathy for those who believed the BS that Uni was the gateway to economic paradise.

The university faculties and education training colleges became infected with leftism even before the schools. They trained the school teachers and administrators whose school output now mirrors the dominant faculty philosophy.

Perhaps they’re fed up with having political correctness crammed down their throats by teachers and others.At 61,I definitely want to turn the clock back culturally!

Is there not somewhat of a distorting effect at work here, that by the young, what we really mean is middle class university students, who are disproportionately more likely to vote and take an interest in politics from an early age?

Lower middle class and working class voters, with more conservative views, tend to become interested in politics later in life and answer political surveys, like the ones quoted above, in such small numbers, that pollsters who have never met these people in their lives, have no idea what they’re really thinking. The last four years might have been a shock to the pollsters but less so if you live outside of the metropolitan bubble.

As young working class white males are the obvious “victims” of the imposition on increasingly shrill and assertive politically correct culture, which now sees them as the mis disadvantaged social group in our society, it is hardly surprising that they move to the right. which recognises their condition. and away from the Left, the source of this disadvantage.

Personal opinion.

Schools are full of teachers that are socialists or further to the left.

My 12 year-old granddaughter came home and announced she would be voting Labour. When asked why, she stated that her teacher had told her it “is the best party”.

I have a real aversion to such behaviour and was furious when I heard what my granddaughter had been exposed to. It is tantamount to grooming, in my opinion, and the teaching profession should be regulated to prevent indoctrination of impressionable youngsters with the political preferences of their teachers.

Unless the subject being taught actually IS politics, in which case the teacher should adopt a neutral posture, any expression of political alignment and any expression of political merit should be outlawed from the classroom. Any teacher proven to be suggesting political expediency or merit to anyone below the voting age should be subject to disciplinary action up to and including dismissal.

This entire article is based upon a very fragile foundation.

It takes voter/poll tendencies between parties that are left or right on face value and completely misses the nuances – ignoring that those parties are not static in their positions on the political scale over time.

Take for example Labour under Corbyn. The party unquestionably moved to the left, leaving more centrist voters stranded. These are then hoovered up by the Tories or UKIP or other as they are not represented by their former party.

You then have taken that as voters becoming more right wing – when the voters have not moved at all.

It also doesn’t take into account voter perception. Most young people might not have strong views either way or be forming their stance on life. But when they see a mainstream party lurch to a more extreme side – they will define themselves in contrary to that. In effect – “I’m not sure what I think – but it’s certainly not that“

3 more possible explanations:

1 – UK Zoomers’ formative experience of “left-leaning party” is Corbyn. That was not a popular approach and would put them off.

2 – Zoomers have not yet entered the job/property market, where lack of opportunity has been the most important driver of radicalism among Millenials and alienated them from centrist and centre-right politics – leading to them then embracing more extreme “liberal” social positions. They feel let down by the mainstream – 18 year olds haven’t got there yet.

3 – Lumping left and liberal into the same box is too crude to provide a useful analysis.

Well, anyone with an ounce of common decency can see that if you push anti semitism, anti-white Brit, anti-male, anti-truth, anti-free speech, and add violence, intimidation, and the desecration of our war memorials, our monuments, and our graveyards into the mix, well, yeh. You’re gonna get push-back from good people. Not all kids are deranged libtards.

I don’t think you can use self-identification as a measure. The whole philosophical atmosphere that we are immersed in (especially in the academy, main stream media, and amongst politicians) has drifted steadily leftward. Even if your positions have not changed it would seem as if you were moving to the right.

To make a meaningful survey of political leaning, one has to go by attitude to specific policy philosophical propositions.

You seem to be assuming that people don’t change their positions? Historically most people generally start social/radical, and then as they get older many become more traditional/libertarian. There is no ‘lump’ of left-wing youth coming up through the ages, there never has been, instead there’s long been a lump of left-wing youth that partly dissipates over time, replaced by more as they arrive.

One explanation for the recent increased left-wingness of <25 years was not that University causes left-wingness, but that working (the horror of paying taxes etc) causes right-wingness. So if you keep people out of the workplace for longer they tend not to shift to right-wing until they are older.

But then I would expected a much greater ‘step change’ when the university student populations rose. But I’m not sure how the university student population proportions changed over time. So, um.

Simply answer is that under 18’s haven’t yet been subjected to three years of university study at the hands of left wing lecturers.

Blair knew exactly what would result from sending 50% of the population to university. Even if 60% of those ended up with worthless degrees most of them would be voting Labour..

The 18-39 year olds have all had their 3 years of indoctrination.

I was at university in the early seventies, the bias was the same then but the reach was much smaller.

I don’t want to be a naughty boy, but suppose the young’uns are starting to realize that the glorious woke war on racism and islamophobia and xenophobia means that native-born Brit kids go to the back of the line.

The difference between young and old in Britain is not about culture. It is about rent.

young people under 40 have decided that they want to be treated as individuals and give their own voice to life,not being herded towards the loud leftist organisations.

It must be mentioned that it is the complete opposite in the US. In the simplest of words, I personally blame this on the constant shoving of the social-liberal and leftist agenda being shoved down young student’s throats. Particularly those in left wing indoctrinating universities, like UCLA and Berkley in California. One of my favourite political commentators, Ben Shapiro described this excellently in his book “Brainwashed” which was a blatant revelation exposing the evil indoctrination constantly driven by both the American MSM and left-wing universities alike.

Nevertheless, I’m currently 18, living in the UK and was simply shocked by this article. It was incredibly interesting and I thank you for your commentary. Admittedly, I have never met a majority of youthful right-wing supporters. The school I am attending in particular is pervaded with socialist and further left-leaning teachers and staff. My English Literature teacher is a perfect example. I previously believed that her pro-Marxist and communist agenda shoving lessons were bad enough. That was, until she went even further to give her personal “preferences” regarding identity politics, culture and whatever lies in between.

All in all, it is obvious that the statistics in the above article prove otherwise. Whatever is the case, I still fear for my generation in particular. Politics is genuinely becoming more polarized by the day in the US. Meanwhile in the UK, the Labour Party and Tories seem to move in the same direction. While Labour is going onto the harder left, the Tories seem to move “centre” towards the Left. Thus, anyone could agree that it is not the people’s opinion that is radically changing, but rather that of the UK political parties.

” removed please delete

Since the previous 2(?) generations intend to stuff on to them the financial cost of their irresponsibility,

and the Chinese Communist Party has them down as obedient slaves to its demands – at c£1 per hour,

they certainly need to ask some questions.

God save the Queen and Joe Biden.

Sleepy Joe the dementia patient will be fine as long as he’s put into a big house painted white and told that he just won the 2020 presidential election.

you refer to ”Populism” as derogatory …The media (Various Newspapers,Opinion polls Gallup yougov etc..) has shown to have feet of Clay regards the Last three General Elections,Last four European Elections & Referendum in 2016,totally Wrong, thankfully Not all The Young buy the ”Global Warming” hysteria and Vox Marxism or Vox capitalism,… On Local issues I am opposed to All 3 parties threatening to Concrete over rural areas…Sometimes one has to join with Unpleasant Xtinction rebellion…but Not all is LOST. Universities in USA are WORSE ..they encourage blocking of Speakers they dont agree with, to ‘Feel’ but not ”reason” …I was Young once…;)

Maybe they will vote in a Marxist government but how long will it last. A UK Marxist government will be no different from any other and will fail. They always do. Then the right wing will get back into power.

This piece seems high on figures and graphs but rather lower on methodology.I hadn’t realised that “Political Correctness was a political commodity to be measured. It has usually functioned either as a derogatory term aimed at lefties like me that tend to argue that we still live in a massively unequal society which it is in our power to alter, or as a preliminary clearing of the throat before saying something deliberately shocking for effect (as in, I know it is not politically correct to say so but I don’t want my child in a school were there lots of ….[add as you wish]).

How do you interpret any answers to the question “are you in favour of political correctness” Would they be different to “Woke” (no don’t lets go there) An imprecise question with the flexibility to support any kind of analysis. The only interesting thing is there seems to be a difference in response based on gender. I suspect that that is an early indication of young men realising that they are not guaranteed in life a wife like their mother or a job like their father as the cards that were previously in their favour have gone. I suspect more men read Jordan Peterson that women

incidentally virtually none of those kids in the picture are paying Johnson any attention. I have faith in the young

Interestingly, the pic has been changed from an earlier one of David Cameron, with ‘young’ people. Maybe there was fear of a Danny Dyer type backlash on the forum…..