In June, UnHerd ran a series of articles called Riven Britain, which looked beyond disparities of income to look at the other inequalities that divide us. For instance inequalities of accumulated wealth, wellbeing and the beauty of one’s surroundings. We also looked at geographical inequality and the profoundly unequal way in which people with learning disabilities are treated.

One inequality we didn’t mention, however, was what one might call existential inequality – between those who believe their lives have meaning and purpose and those who don’t.

A YouGov survey commissioned for a report by the libertarian Cato Institute reveals significant existential inequalities between Americans.

The comparatively good news is that 83% of the 1,700 respondents agree with the statement that “I feel like I have purpose in my life; my life has meaning.” However, only 46% strongly agree.

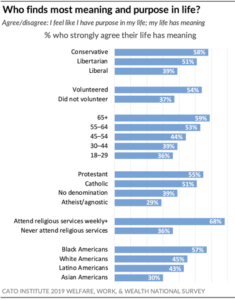

So who are the 46%? Demographically, they tend to be older, more religious and more conservative (a lot of overlaps there). Some of the disparities are stark – 59% of the 65+ age group strongly feel their lives had meaning versus 36% of the 18-29 year olds. There are big gaps too between conservatives (58%) and liberals (39%); and between those who attend religious services more than once a week (68%) and those who never do (36%). The gulf between volunteers (54%) and non-volunteers (37%) is worth noting too.

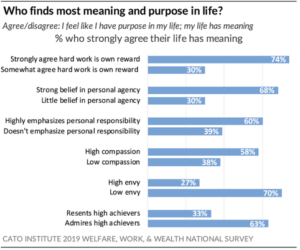

In terms of attitudes to life, the survey finds that a strong sense of purpose is associated with a strong belief in things like hard work, personal responsibility and compassion. It is negatively associated with envy and resentment of high achievers.

Unsurprisingly, a further correlation is between a strong sense of purpose is also correlated and a strong sense of personal agency – and thus the cynical interpretation of all of this is that purpose is a function of privilege: if you have the money and power to achieve your objectives then of course you consider your life to be meaningful.

But is this true? I took a look at the survey’s data tables to see if the purpose and meaning results were broken down by income and education level. And, sure enough, they were (see page 21 of this document).

It turns out that these material factors did make some positive contribution to feeling of purpose, but not a great deal on the whole – and certainly less than the factors mentioned above.

It’s also worth noting that black Americans – who are, on average, less economically advantaged than white Americans – were more likely to strongly agree with the purpose and meaning statement (57% to 45%).

In short, existential inequality is not a simplistic function of privilege. Nevertheless, should we care that some people find a lot more meaning in life than others?

America’s Declaration of Independence majors on “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” But happiness and a sense of purpose are not necessarily the same thing – one can have one without the other and I suspect that many people would prefer to believe that their lives have no particular purpose, thereby leaving them free to pursue mere pleasure.

And yet while happiness is, at best, fleeting – a belief that life has meaning can help one through the unhappiest of circumstances. So, yes, purpose – and therefore lack of purpose – matters very much.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe